Trump’s Newest Tariff Threat Ripples Across 2020 Battlegrounds

Trump’s Newest Tariff Threat Ripples Across 2020 Battlegrounds

(Bloomberg) -- The economic damage of U.S. tariffs on Mexican goods would tear through battleground states that President Donald Trump needs to win re-election, hurting the auto industry in Michigan and Ohio, dairy farmers in Wisconsin and grain and hog farmers in Iowa and North Carolina.

In a pair of tweets Thursday night, Trump warned he’d impose tariffs on Mexico starting at 5% on June 10 and ramping up in increments to 25% in October unless Mexico stops immigrants from entering the U.S. illegally.

Industry advocates, including manufacturers and various agricultural commodity groups, issued dire warnings about the fallout from tariffs. The powerful U.S. Chamber of Commerce said it’s considering a legal challenge.

Trump’s pivot to using tariffs in a bid to fulfill his campaign pledge to end the flow of undocumented immigrants to the U.S. could back-fire if it dings U.S. economic growth. On Friday, Trump further entwined the tariff threat with a crackdown on the drug trade, saying tariffs are “about stopping drugs as well as illegals!”

Jay Timmons, president and chief executive officer of the National Association of Manufacturers, called the threats “a Molotov cocktail of policy” that would have “devastating consequences on manufacturers in America.”

A top Mexican official said the country won’t retaliate before discussing the matter with the U.S. Still, the potential tariffs, “if turned into reality, would be extremely serious,” said Jesus Seade, the country’s undersecretary of foreign relations for North America.

Retaliation by Mexico is virtually certain to strike Trump’s political base in rural America. Farmers are already under strain from ongoing trade wars, low commodity prices, and natural disasters including spring flooding across the Midwest.

Agricultural groups had been relieved just two weeks earlier when Trump moved to end a trade dispute with Mexico by ending tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from the country. Now, they face the prospect Mexico will resume punitive duties on U.S. agricultural goods.

Chris Kolstad, chairman of U.S. Wheat Associates, a grower-financed group that promotes exports, and a wheat farmer from Ledger, Montana, compared the potential fallout to “struggling to survive a flood then getting hit by a tornado.”

Trade Deal

Farm groups fear a new trade dispute will hinder ratification of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement -- intended to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement -- which they consider crucial to maintaining trade with the nation’s two largest agricultural export markets.

House Agriculture Committee Chairman Collin Peterson of Minnesota said in a radio interview Friday that a trade fight with Mexico “is really going to throw a wrench into” efforts to pass USMCA.

Dairy and pork producers will be in cross-hairs if Trump resumes a trade fight with Mexico, which hit both industries with punitive tariffs in the most recent trade dispute. The country is also the largest export market for U.S. corn and wheat, and the second-largest for soybeans, behind China.

Agricultural and industrial regions played an important role in Trump’s electoral map in 2016. He won an Electoral College majority and the presidency based on a combined margin of fewer than 80,000 votes in three states: Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

The largest agricultural sector in each of those three states is dairy. Mexico is “our number one market,” Tom Vilsack, president and CEO of the U.S. Dairy Export Council and a former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, said in an email.

Iowa, which voted for Trump in 2016 after supporting Democrat Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012, is the largest U.S. producer of hogs and of corn. North Carolina, another electoral battleground, is the nation’s second-largest hog producer.

Retaliation Fears

David Herring, president of the National Pork Producers Council and a hog farmer from Lillington, North Carolina, urged Trump to reconsider.

“American pork producers cannot afford retaliatory tariffs from its largest export market, tariffs which Mexico will surely implement,” Herring said in an emailed statement.

Trade disputes with Mexico and China already have cost U.S. pork producers $2.5 billion over the past year, Herring said. The two rounds of financial aid the Trump administration has announced for farmers “provide only partial relief to the damage trade retaliation has exacted,” he said.

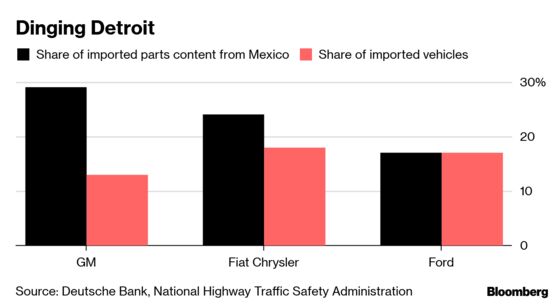

Trump’s latest tariff barrage, meanwhile, would immediately hit the vast, tightly integrated supply chains of U.S. automakers, a bedrock industry in Michigan and northern Ohio. Both are states Trump carried in 2016 but are vulnerable to a Democrat, particularly front-runner Joe Biden, who has shown appeal to working-class voters.

Trump already took a hit in northern Ohio in March when GM halted production at its small car factory in Lordstown, located in a region where the president had promised industrial jobs would be coming back and implored residents not to sell their homes.

Mexico is the largest source of parts for U.S.-made autos, meaning tariffs would increase costs for virtually every major manufacturer. Higher prices at the dealership would cut into sales that are already expected to decline for the second time in three years.

Even before the tariff announcement, General Motors Co. and Ford Motor Co. had announced planned to cut thousands of salaried jobs.

Auto industry analysts brushed aside an assertion by Trump that companies will leave Mexico and “come back home to the USA” in response to tariffs.

“Until there’s some greater certainty about how long these tariffs would be in place, nobody is going to be moving billions of dollars and putting in duplicative capacity in the U.S.,” Kristin Dziczek, vice president of industry, labor and economics at the Center for Automotive Research in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

“The U.S. is a high-cost region for production. If you’re going to be paying huge tariffs in Mexico, where you’ve been getting low-cost production, there’s lots of other low-cost countries you can go to,” she said.

No automaker has halted production at a Mexican factory since Trump took office, Dziczek said. In fact, Ford recently said it would begin building commercial vans in Mexico, while Fiat Chrysler this year reneged on plans to move heavy duty truck production to Michigan from Mexico. GM is building its new Chevrolet Blazer in Mexico, even as it plans to close four vehicle and parts plants in the U.S.

For the car companies, moving production back to the U.S. “would take a lot of money and a lot of time,” Dziczek said. “And it’s not clear that these tariffs are going to last very long.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Mike Dorning in Washington at mdorning@bloomberg.net;Keith Naughton in Southfield, Michigan at knaughton3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Joe Sobczyk at jsobczyk@bloomberg.net, Ros Krasny

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.