Trump Steps Into a Mexican Labyrinth

Trump Steps Into a Mexican Labyrinth

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Global supply chains have become deep and labyrinthine. So when President Donald Trump says he’s slapping tariffs on products that move across the U.S. and Mexican border, there’s a lot to unpick. But one thing is clear: American consumers will be hit the hardest.

The U.S. will impose a 5% tariff on all goods imported from Mexico starting June 10 to address the “emergency” of illegal immigration across its southern border, Trump said in a White House statement Thursday evening. If the situation doesn’t improve, that will rise to 10% on July 1 and reach 25% on Oct. 1.

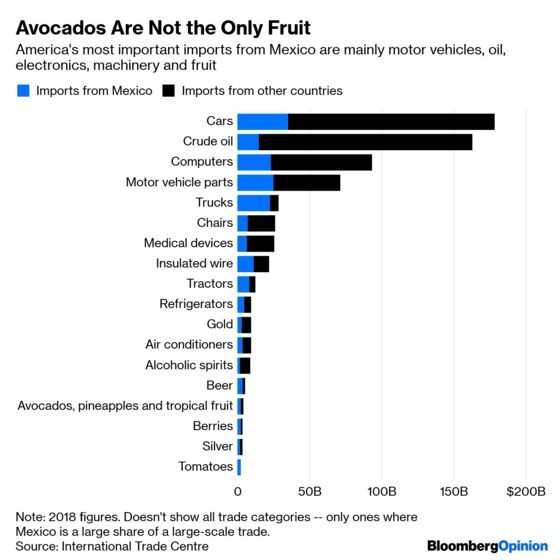

Many products and parts cross the U.S.-Mexico border multiple times. That will magnify the impact of tariffs. About $53 billion of the value added in Mexican exports originates in the U.S., equivalent to about one-seventh of the total value of Mexican exports. Some $14 billion of the value added in U.S. exports comes from its southern neighbor.

Much of that is concentrated in high-value industries close to the border. Mexico accounts for about a quarter of U.S. exports of machinery, electronics and plastics, and roughly a fifth of its petroleum and cars.

Take autos. Parts come from all over the world, including the U.S. itself, before being assembled into a vehicle. A seat and seat belt may come from a Mexican supplier, while a specialized valve for air conditioning comes from China and other gear from Germany. Such supply chains have not only reduced costs but also raised the quality of products for American car buyers.

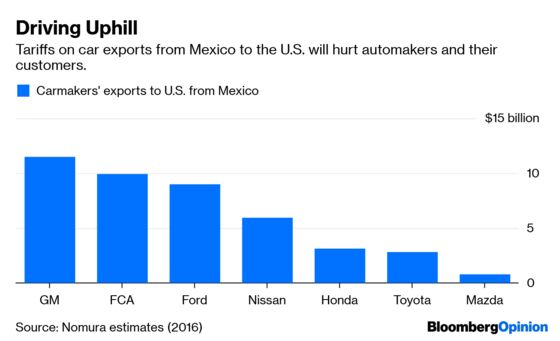

More than 3 million vehicles and related parts enter the U.S. from Mexico every year, a trade worth around $90 billion. American carmakers export more than $30 billion from Mexico to the U.S., and Japanese manufacturers a further $13 billion. For every car an American consumer buys in the U.S., a third of the value is created by Mexican workers and parts. Out of Mexico’s imports of intermediate goods, about 60% leaves the country again as exports.

Tariffs will rip these supply chains apart, raising the price of every part and product.

Making a car isn't just about importing and exporting chassis, engines and transmission parts. For every component, the supply chain can go 20 layers deep. It’s a complex undertaking that draws in industries from electronics to textiles across the world. Consider a car seat. Some factories make frames; others produce foam cushions; still others manufacture the electronics that move the seat backward and forward. Other plants perform assembly into a seat that’s ready to be fitted into a vehicle.

Many of the costs in cross-border manufacturing are hidden and therefore incalculable. Import prices don’t reflect intermediate goods and so it’s difficult to track such products through trade data. These hidden costs won’t become immediately apparent.

Higher prices resulting from tariffs have already cost U.S. consumers and importers close to $70 billion, economists estimate. That’s offset income gains for American producers from the trade war.

Here’s the rub: A significant chunk of the products the U.S. imports contain American parts. The proportion is about 40% to 50% for motor vehicles exported from Mexico to the U.S. Tariffs end up being more expensive to the country imposing them when imports have more domestic content, recent research has shown. That’s because the levies ripple back and hurt suppliers at home.

Billions worth of parts flow in to support the economies of American states: Michigan gets more than $15 billion of intermediate goods from Mexico; Canada and Mexico supply $3 billion of parts to Ohio; Texas imports $6 billion of parts from Mexico, Tennessee $2 billion and Kentucky $1.6 billion, according to the Brookings Institution.

For automakers, tariffs will erode profits by hundreds of millions of dollars. Those already in place by the end of 2018 cost firms about $14 billion a month in redirected trade, according to a study in March. That reflects the high costs of moving supply chains. These expenses will inevitably be passed on to consumers.

Trump’s tariffs may also reduce choice for consumers by pushing Mexico to pursue trade with other partners such as the European Union. The country has 11 free-trade agreements that involve 46 countries. A renegotiated accord with the EU is expected to allow tariff-free movement of all goods.

Whether trade wars are easy to win may depend on who pays the price. In this case, it’s looking mostly like the American consumer.

The will rise to 15% on Aug.1 and 20% on Sept.1.

While imports of refined oil products aren't as high, they havea U.S. value added share --close to 80%.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.