Trump Attacks on Fed Could Backfire, Boosting Powell's Support

Trump Attacks on Fed Could Backfire, Boosting Powell's Support

(Bloomberg) -- President Donald Trump’s attacks on the Federal Reserve may hold a silver lining for Chairman Jerome Powell: preserving unity among colleagues who can sometimes go rogue.

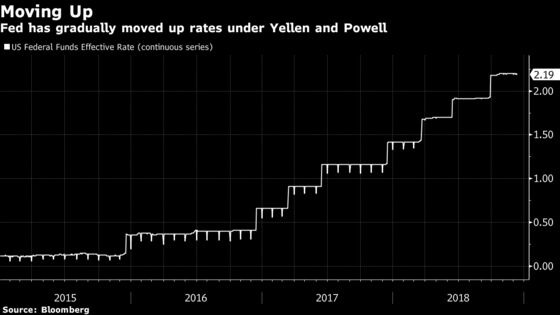

America’s central bankers have a strong culture of closing ranks during times of strain to defend the chair and preserve institutional independence. Even though there’s an argument for holding interest rates steady, Trump’s pressure may make any dissent less likely at the Dec. 18-19 meeting when a fourth quarter-point increase this year is widely expected.

“FOMC members will stand behind Powell,” said William Poole, former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, who regularly dissented at meetings of the Federal Open Market Committee during a 10-year term ending in 2008. “There is a powerful culture of an independent Fed” and policy makers will want “to avoid any hint of siding with Trump.”

Trump renewed his criticism on Thursday in an interview with Fox News. “Hopefully the Fed won’t be raising interest rates anymore,” he said. “I’m almost at a normalized interest rate and yet our economy is soaring.” He’s been criticizing Powell in tweets and public comments for months, accusing the central bank of undermining economic growth by hiking rates.

Powell has encountered no dissents since becoming chairman in February. By contrast, 22 dissenting votes were cast against his predecessor Janet Yellen over four years, and 48 against Ben Bernanke over eight years. Both periods were intensely challenging for officials as they battled the Great Recession and its after-effects, spurring a spirited debate over the correct policy response.

Fed presidents have dismissed Trump’s criticism, saying higher rates are based on data and analysis. New York Fed President John Williams said on Dec. 12, he is committed to “making the tough calls.” The Atlanta Fed’s Raphael Bostic said in October that “we have to do what we think is best.”

Bostic has been seen as a possible dissenter next week. He pledged in August that he wouldn’t vote for anything that would knowingly invert the yield curve -- that is, raise short-term bond yields above longer-term ones, which some see as a signal of a coming recession. With 10-year yields already close to the 2-year equivalents, inversion is an imminent risk if the Fed raises rates again.

St. Louis’s James Bullard, the most dovish participant on the FOMC based on his recommendation to keep rates on hold for several years, becomes a voter in 2019 in the annual rotation among regional bank chiefs.

Also voting next year will be Chicago Fed’s Charles Evans, a past dove who’s moved to the center as the job market has tightened, and Kansas City Fed President Esther George and Boston’s Eric Rosengren, who have been hawkish in recent years.

Sooner or later, someone will almost certainly break ranks under Powell. The last chairman to serve without dissents was Thomas McCabe, whose term ended in 1951. Still, three or more ‘no’ votes at a single meeting might give the impression of a divided central bank.

Fed chairs, while publicly embracing dissents, have tried behind the scenes to head them off. Bernanke, in his memoir ‘The Courage to Act,’ recounted his conversations and calls with various Fed presidents and governors before critical meetings, as he sought to drum up votes. He described his gratitude after Governor Kevin Warsh voted in favor of a second massive round of Fed bond purchases in 2010, despite strong personal qualms.

A sense of responsibility to support the chairman also weighs on committee members, who have on occasion initially dissented and then put aside their objections to show support, said Dennis Lockhart, a retired Atlanta Fed president who never dissented.

There’s a “strong impulse” to show consensus, said Lockhart. “Committee members will vote what each really thinks is the right policy, but if on the fence, might lean away from a dissent.”

They’re even more likely to do so when they’re under external attack, said Princeton University economist Alan Blinder, a former Fed vice chairman.

“Would-be dissenters may pull their punches when the criticism is coming from the White House or Congress,” he said.

--With assistance from Alex Tanzi and Jeanna Smialek.

To contact the reporter on this story: Steve Matthews in Atlanta at smatthews@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alister Bull at abull7@bloomberg.net, Ben Holland

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.