Trump Moves From Trade War Toward Currency War

President’s ECB tweets mark rare intervention by a U.S. leader.

(Bloomberg) --

President Donald Trump has already given the global economy trade wars. Now there are signs he may be gearing up for a currency war, too.

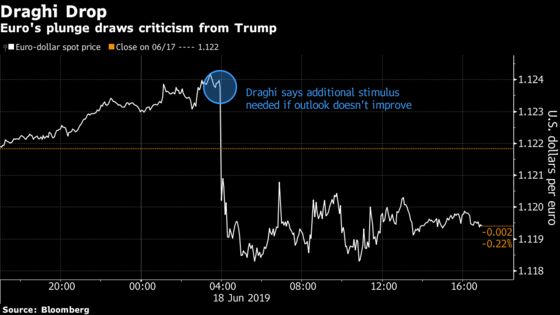

With a series of tweets on Tuesday aimed at the European Central Bank and an announcement by Mario Draghi, its president, that he was prepared to cut interest rates further below zero in response to Europe’s slowing growth, Trump made a rare American presidential intervention into another economy’s monetary policy.

“Mario Draghi just announced more stimulus could come, which immediately dropped the Euro against the Dollar, making it unfairly easier for them to compete against the USA. They have been getting away with this for years, along with China and others,’’ he tweeted. Later, he added: “German DAX way up due to stimulus remarks from Mario Draghi. Very unfair to the United States!’’

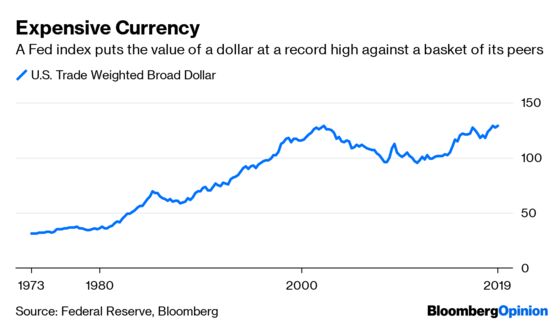

It was not the first time Trump has blamed currency manipulation overseas for a strong dollar that raises the cost of U.S. exports. He has already become unique among recent American presidents in a shift away from the “strong dollar’’ policy of his predecessors.

By targeting Draghi directly and responding in real time to an overseas central bankers’ policy pronouncement, Trump was dialing up the heat -- just as his own Federal Reserve was gathering in Washington to decide on rates in a decision expected Wednesday. Coming just days ahead of a summit with other Group of 20 leaders in Japan, the salvo served to highlight his administration’s increasingly aggressive currency policies and the place he sees for them in his trade arsenal.

“They are preparing the ground, they are laying out the potential tools they may have at their disposal,’’ said Cesar Rojas, global economist at Citigroup Global Markets Inc., though he added “we’re not at a currency war just yet.’’

Finance ministers and central bankers this month agreed that a currency war -- a tit-for-tat push at times of slow economic growth to actively weaken foreign-exchange rates in order to boost exports -- is in no one’s interest. They reaffirmed commitments made in March 2018 to refrain from competitive devaluations.

Last month, the U.S. Treasury increased the number of economies it scrutinizes to 21 from 12 and expanded its watch list from four to nine, adding countries such as Ireland, Italy and Singapore under new tougher criteria. It again refrained from labeling China a manipulator.

The Commerce Department on May 23 proposed allowing U.S. companies to seek trade sanctions against goods from countries with “undervalued’’ currencies, though it said it did not intend to target independent central banks or their monetary policy decisions. The administration has also been pushing to include currency provisions carrying the threat of sanctions in new U.S. trade agreements.

There are plenty of economists who argue the U.S. should take a more forceful approach to addressing currency manipulation by trading partners. Some have even called for a 21st century Plaza Accord, the 1980s agreement that saw countries including Japan agree to engineer a devaluation of the dollar under pressure from the Reagan administration.

Top Priority

In a paper released this week, Brad Setser, a former U.S. Treasury official now at the Council on Foreign Relations, argued that “countering currency intervention by foreign governments should be a top priority of U.S. international economic policy.’’ If nothing else, other countries’ manipulation hurts the U.S.’s ability to use exports to recover following economic downturns, he wrote.

In an interview on Tuesday, however, Setser said that Trump’s ECB intervention was misplaced, largely because Draghi’s comments were aimed at domestic conditions.

“Most of the world recognizes that the ECB has failed to meet its inflation target and that with a slowing European economy there is pressure on the ECB to ease policy,’’ he said. Worse, Trump’s intervention could be seen as its own form of market manipulation, Setser said, and “feeds into a building narrative in Europe that the U.S. is a rogue actor under a rogue president.’’

Trump has defied convention in a number of other ways, including his repeated criticisms of Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell for raising interest rates. He asked White House lawyers earlier this year to explore his options for removing Powell as chairman.

Joseph Gagnon, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and another advocate of stronger U.S. currency policy, said the world was in an “uneasy peace’’ over currencies with China and other G-20 countries having in recent years accepted a U.S. push to refrain from competitive devaluations. In a June 6 note, Gagnon and a co-author said interventions by countries to weaken their currencies to affect their trade balance fell in 2018 to the lowest level since 2001.

But the G-20 commitments are weak and “if there’s a global downturn, a global recession, countries would be very tempted to violate these terms and try to claim special circumstances,’’ he said. “There’s really no regime in place to sanction them or hit them, except the U.S. might do something.’’

Trump may have some legitimate reasons to grumble. The “Big Mac” approach to gauging currency valuations shows the euro is about 15% too cheap. Since Trump launched his trade wars, China’s yuan has also fallen against the dollar, prompting the president to complain that it was undermining the impact of his tariffs and his efforts to raise pressure on Beijing.

Those currency moves are widely seen as related to the weakening of the European and Chinese economies and a global economy that is looking increasingly fragile thanks in part to Trump’s trade wars. The fear, however, is that Trump’s anger over the currency shifts could also help fuel further trade actions, including tariffs he has threatened to impose on imported cars and parts from the EU but put on hold for 180 days.

A drop below 1.10 for the euro-dollar rate could inflame Trump’s temper and make him more likely to impose those auto tariffs, according to Jens Nordvig, the founder of Exante Data LLC. The rate fell as low as 1.1181 on Tuesday after Draghi said additional stimulus may be needed and Trump levied his latest Twitter missive.

To contact the reporters on this story: Shawn Donnan in Washington at sdonnan@bloomberg.net;Rich Miller in Washington at rmiller28@bloomberg.net;Katherine Greifeld in New York at kgreifeld@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Kennedy at skennedy4@bloomberg.net, Malcolm Scott, Brendan Murray

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.