The Outsider Who Will Decide If Brexit Is Good for Britain

The Outsider Who Will Decide If Brexit Is Good for Britain

(Bloomberg) -- Google “Clare Lombardelli” and one of the first items to come up is a description of a fight at the top of government, in which a furious Cabinet minister angrily dismissed her as “that woman.”

It was 2010 and Lombardelli was working as a senior official for George Osborne, then chancellor of the exchequer, during his battle with the work and pensions secretary Iain Duncan Smith over welfare reforms. According to reports at the time, Lombardelli stood her ground during the argument, telling Duncan Smith his proposals were “unworkable,” a verdict that provoked the angry minister to demand she “show some respect.”

Scroll forward eight years and both Osborne and Duncan Smith are out of the Cabinet, but Lombardelli is more powerful than ever.

As the first female chief economic adviser in the Treasury – and the government’s most senior economist – the 39-year-old has a lot on her plate. She’s responsible for advising ministers on the outlook of the British economy – and crucially assessing the likely impact of Brexit. As Prime Minister Theresa May seeks to finalize the terms of the U.K.’s divorce from the European Union, fears are growing inside the government and elsewhere in the bloc over the prospect of a chaotic “no deal” departure.

If May succeeds in striking an agreement with the EU by the agreed October deadline, it will be Lombardelli who has to analyze whether the terms of the exit treaty will work for the economy.

As the Cabinet divisions over Brexit show, the process of formulating policy can provoke fierce arguments. Independent officials such as Lombardelli can find themselves caught in the crossfire between politicians. The secret is to be prepared, especially if you’re a woman – and even then you can still end up being labeled by colleagues as either a “nice” female co-worker or a “bitch.”

“If you are a woman with a view, you might find yourself nearer the ‘bitch’ end,” Lombardelli said in an interview. “You have to do your homework and then be clear in what your position is.”

More than her gender, Lombardelli feels her social background makes her different from many of the people she works with. She grew up in post-industrial Stockport, Greater Manchester, a northern town with a working-class heritage, where old mills from the Victorian textile industry and the railway viaduct still dominate the skyline.

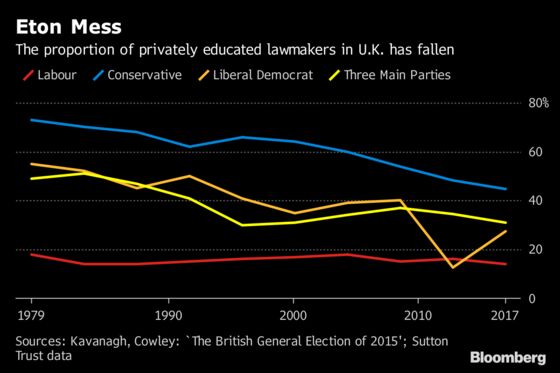

After attending her “quite rough” local state-funded school in the 1980s and 1990s, she went to Oxford University, where she felt like an outsider. She was confronted with an intimidating display of wealth and privilege (her college boasted its own deer park, and most of her fellow students attended expensive, fee-paying private high schools). “It was quite a surprise to me,” she said.

When former Prime Minister David Cameron and ex-Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson studied at Oxford a decade before Lombardelli, they joined the exclusive Bullingdon dining club. Members of the 200-year-old all-male establishment, many from aristocratic families, wear waistcoats and tails and has a reputation for rowdy and drunken behavior.

While working for Cameron years later, Lombardelli noticed how he and his inner circle – many of whom went to elite schools like Eton College – felt comfortable in their roles at the top of government. Unlike her, they never seemed to question whether they belonged in power. “There’s almost a sense of entitlement,” she said.

Yet Lombardelli said she thinks her sense of being “an impostor” drove her to work harder.

“If you’re not confident, you do put quite a lot of effort into making sure you know your brief and you can end up as being described as things like ‘brittle.’ Actually it’s possibly because you rely too much on the content and a bit less on the schmoozing,” she said.

One Treasury official, who asked not to be named, said Lombardelli’s resolve could be just what Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond needs as he faces an onslaught of criticism from hardline euroskeptics such as Johnson, who believe he’s plotting to reverse Brexit.

Johnson, who led the Vote Leave campaign in 2016, has accused Hammond’s department of being “the heart of Remain.’’ Leaked economic forecasts from the Treasury in March, which showed all Brexit outcomes would make Britain poorer, were dismissed by Brexiteers as “project fear.’’ Hammond will rely on Lombardelli to provide sober advice on how a future trade deal with the EU – as well as pacts the government strikes with other countries – could impact the U.K. economy.

Nick Macpherson, who worked with her at the Treasury when he was permanent secretary, said her appointment in January this year was “inspired’’, describing her as both “rigorous’’ and “courageous.’’

But even Lombardelli’s record isn’t perfect. In 2012, Osborne announced a new tax on hot takeaway food – and it proved disastrous, ultimately plunging him into one of his worst spells in office.

The Treasury failed to spot that the policy would disproportionately hit people who regularly eat cheap, takeaway foods like Cornish pasties – the inexpensive British snack consisting of meat and vegetables in a pastry case. Under questioning by a parliamentary committee, Osborne was forced to admit that he couldn’t remember the last time he ate a pasty from a popular bakery chain.

He later abandoned the planned tax amid criticism that he was out of touch with voters. It had been rumored that Lombardelli was the lone voice of reason, urging Osborne not to pursue his plan before he announced it, though she said that’s not the case. Still, there are lessons to be learned.

“It is a good example of how politicians and civil servants need to have a better sense of the country they are serving and why we really need a diverse workforce to understand these things,” she said. “We were all talking about what foods are popular, but none of us ever thought about Cornish pasties.”

Understanding the population is more important than ever for May’s government as it seeks to negotiate a divorce with the EU that satisfies a country that Brexit has split down the middle.

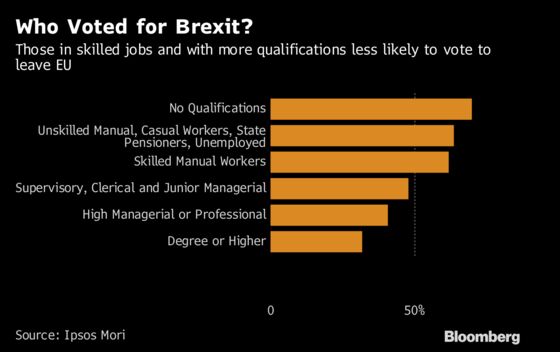

University educated people, those living in London, and employees in highly skilled work – in short, the kind of people who work alongside Lombardelli – voted overwhelmingly to remain in the bloc. Outside these groups, voters in declining coastal towns or post-industrial cities opted in large numbers to leave the EU. In Cornwall, the home of the Cornish pasty in the far southwest of England, 57 per cent voted for Brexit.

While Stockport as a whole voted to remain, the north of England largely chose to leave the EU. Lombardelli grew up around a mixed group of people. She was in the first generation of her family to go to university and she knew people who left school at the age of 15 or 16 without qualifications – matching the profile of many Brexit voters. That helps her see the value of an outsider’s perspective when the government is deciding on policy that affects people’s lives, she said.

“The thing that’s most important to me is diversity of thought,” she said. That means taking on board the views of people with different experiences and from different backgrounds. “It is a really important part of your job, if you’re in public service, to understand the country that you are serving.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tim Ross at tross54@bloomberg.net, Stuart Biggs

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.