(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If you’re looking for a glimmer of hope that China’s trade talks with the U.S. are still on track, how about this: The country is considering buying as much as 7 million metric tons of American wheat, people with knowledge of the matter told Bloomberg News. That follows a report in December that it may buy up to 3 million tons of corn from the U.S., too.

But don’t get too carried away. While such an amount would certainly represent an increase from current levels — depending, crucially, on what period it would be bought over — there’s precious little evidence that Beijing is about to open up trade in its two most protected sectors.

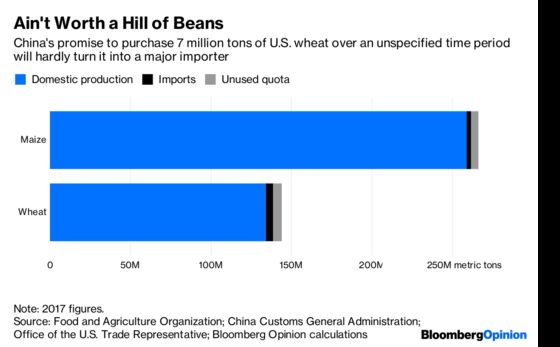

There is no product on the planet on which China imposes higher tariff rates than for wheat and corn, considered essential for food security. As a result, global imports amount to just a percentage point or so of Chinese consumption.

Only rice (and, bizarrely, flavored grape wines such as vermouth) attract the same 65 percent levy as wheat and corn — an impost that now rises to 90 percent for U.S. products, given Beijing’s 25 percent retaliatory tariffs. The border tax on soybeans, by contrast, tops out at 3 percent.

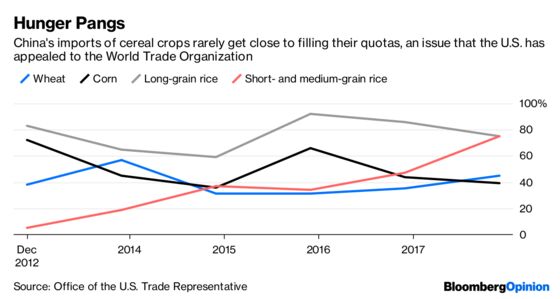

To be sure, there’s a quota that gets in with a 1 percent tariff, but these amounts are too small to make much of a difference. A maximum of 9.63 million metric tons of wheat, 7.2 million tons of corn, and 5.32 million tons of rice was allowed in during 2017, divided between all the world’s exporters — and even that small amount wasn’t fully utilized, an issue the U.S. is appealing to the World Trade Organization.

China’s promises to buy more foreign goods — while a natural consequence of the country’s rising wealth — are mostly a red herring in the context of the current tensions, as Bloomberg columnist Noah Smith wrote recently.

China’s most likely immediate sources of rising imports are raw materials, petroleum and farm products. Yet the dispute between Beijing and Washington centers on the opposite end of the economic value chain: advanced technology, intellectual property and services.

Should China choose to break with global tradition and start reducing its swingeing cereal tariffs — or at the very least increase its quotas, or even use the full quotas already in place — that would be a good thing for the world’s farm belts. It seems unlikely that such dramatic changes are in the offing, though: Even the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement that went into force in 2015 failed to budge Beijing’s policy on wheat, Australia’s second-biggest agricultural export.

In the meantime, promises to buy more via existing channels should be seen as the opposite of a breakthrough — a sign that Beijing’s negotiators are only bringing shiny trinkets to the table, rather than anything substantive. Only hayseeds should be taken in.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.