Tomorrow's Jobs Demand Higher Degrees as Economic Fates Diverge

Tomorrow's Jobs Demand Higher Degrees as Economic Fates Diverge

(Bloomberg) -- This century has already been tough on Americans with only a high school education. The current decade is poised to add insult to injury.

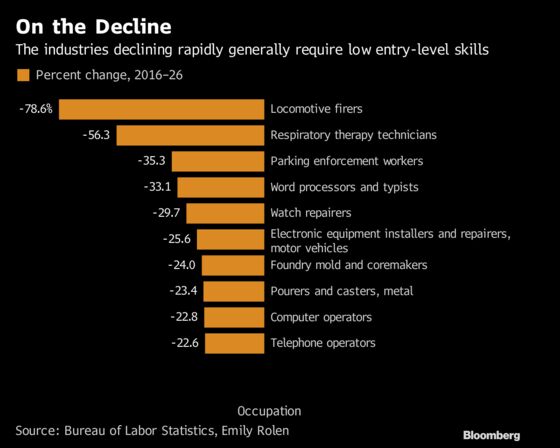

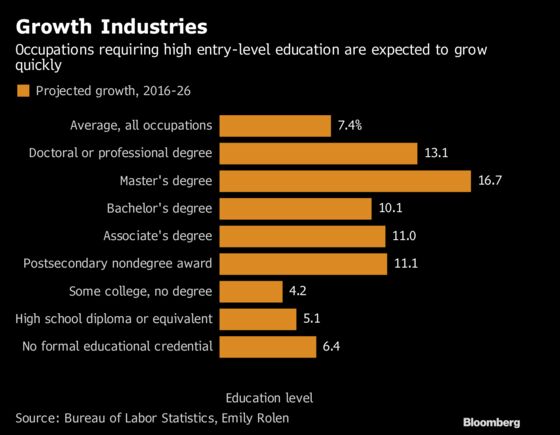

The fast-declining occupations between 2016 and 2026 are those with minimal entry-level education requirements that are vulnerable to automation and other technological advances, based on a Bureau of Labor Statistics report by economist Emily Rolen. The fastest-growing fields require post-secondary education, often master’s degrees.

In fact, occupations requiring master’s degrees are expected to grow at a rate of 16.7 percent through 2026, versus 7.4 percent for all occupations. Ph.D.-requiring gigs will grow second-fastest, at 13 percent, followed by jobs requiring associate’s and bachelor’s degrees. Health care is a big reason. Many jobs in the booming sector have high education requirements, even for entry-level positions.

To be sure, growth rates are relative: a comparatively small share of jobs required master’s degrees in 2016, so it’s easy for the group to grow quickly. But it speaks to the broader shift going on in the American workforce, one in which high-paying, skilled jobs will continue to enjoy high demand. Rolen’s analysis shows that most occupational groups destined for above-average growth over the next decade already pay more than the median wage -- and the bulk of them require a bachelor’s degree or more.

While health care support and personal care occupations will also grow very quickly and require just a high school education, both offer below-median pay.

(You’re reading Bloomberg’s weekly economic research roundup.)

Fortunately for employers and employees alike, educational attainment is improving. Nearly 48 percent of American adults between the ages of 25 and 34 had earned an associate’s degree or more in 2017, up from about 40 percent a decade earlier. Still, these trends suggest Americans’ economic fates will continue to diverge by schooling -- important in a world where such divides are already widening the economic gap between urban and rural areas and deepening political fissures.

These are long-running trends, but we’ll be able to see them coming to bear in real time this week when the Labor Department releases the January employment report on Friday. Check out Table B-1 for a breakdown of employment growth by industry.

Also worth a read this week...

Speaking of jobs day, here’s a new and nerdy way to think about the data. In this post, University of Melbourne economists take a fresh look at Okun’s Law, the idea that a given increase in the cyclical unemployment rate will create a given hit to real GDP.

They focus on workers moving between three categories: employment, unemployment, and out of the labor market. They find that neither net flows from unemployment to outside of the labor force nor flows from employment to outside are sensitive to changes in growth. Flows between employment and unemployment are, and they respond more to contractions than to expansions, so the relationship between job market changes and growth is stronger in downturns. “This result likely reflects the observation that it is easier to lay-off workers in recessions than it is to hire workers in a boom,” the authors write.

India’s 2016 demonetization -- which made 86 percent of cash in circulation illegal tender overnight -- cut output growth for the fourth quarter by 2 percentage points relative to growth if there had been no such action, Harvard University’s Gita Gopinath and her colleagues find in this working paper. Gopinath started this month as chief economist at the International Monetary Fund.

She and her colleagues examined the intensity of lights at night as measured by satellite, along with employment surveys, consumer transactions, and other metrics. “Unlike in the cashless limit of new-Keynesian models, in modern India cash serves an essential role in facilitating economic activity,” they write, although they’re sure to stress that their focus is short-term and the paper may have missed some longer-term advantages.

China’s financial policies have driven three distinct economic phases since the country began opening up in the late 1970’s, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta researchers argue in this essay: first an era dominated by reforms in state-owned enterprises from 1978 to 1997, then a period of heavy investment in large and capital-intensive enterprises between 1998 and 2015, and most recently a transition to a new-normal economy with improved monetary and regulatory coordination. The latest phase has also been marked by a monetary policy transition from a money quantity-based framework to an interest-rate based framework.

“The effects on the macroeconomy of a regime switch in monetary policy to an interest rate based framework are unknown and difficult to measure at this point,” the authors write. “Nor is known about how effective is the monetary transmission from the policy rate to interbank interest rates and eventually to bank lending rates.”

Such transition won’t be smooth so long as gross domestic product remains the monetary policy goal, the authors write. “We conclude that the heavy hand of government in influencing how commercial banks allocate their loans will continue, making M2 growth an effective tool for monetary policy not only in the past but also in the near future.”

--With assistance from Luke Kawa.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeanna Smialek in New York at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull, Jeff Kearns

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.