This Shopkeeper Knows Why Britain’s Business Rescue Fell Flat

Big banks moved away from servicing small companies, but now they’re key players in the emergency plan to save them.

(Bloomberg) -- When Yvonne Lin contacted her bank, HSBC Holdings Plc, for an emergency business loan in March she knew the process was going to be tough. The economy was grinding to a halt and even though the U.K. government was covering 80% of the risk for loans to firms like her London fashion boutique, most companies, including the country’s biggest lenders, were struggling to adapt to a new reality.

But Lin had expected she’d at least get a call back.

Instead, it took the 33-year-old businesswoman four days to get a bank representative on the phone and then almost a month of conversations and emails and interminable waits on hold just to apply to the Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme. In the end, HSBC rejected a loan for Zelle Studio Ltd. Lloyds Banking Group Plc also turned her down.

“It all sounds great when the government says, ‘We are guaranteeing loans and encouraging banks to do what they can,’ but the reality is that’s not happening,” Lin said. “The banks can take as long as they want to assess your case and they can still say no. I feel they’re just doing what they normally do rather than seeing this as an extraordinary circumstance.”

An HSBC spokeswoman said the bank has apologized to Lin for the delay and ensured any other needs have been discussed. A Lloyds spokesman said high demand means it’s extending CBILS loans only to existing customers for now.

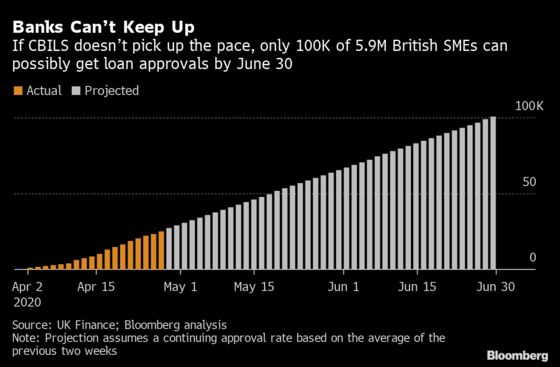

Lin is one of numerous small business owners who’ve been stymied in accessing the U.K.’s loan program and getting the financial help they need to ride out the pandemic. As of April 30, CBILS, as the initiative is known, had distributed just 4.1 billion ($5.1 billion) pounds in loans to more than 25,000 small and medium-sized companies.

While it’s hard to compare it to similar efforts in other countries because they collect and collate the data in different ways, the indications are that CBILS is a laggard. In France, official data shows banks have issued state-guaranteed loans to more than 200,000 small enterprises while Germany’s guaranteed lending program has delivered 33 billion euros ($36 billion) to companies of all sizes. In the U.S., lawmakers recently allocated $320 billion for their small business rescue plan after banks already burned through $349 billion in loans fully backed by Washington.

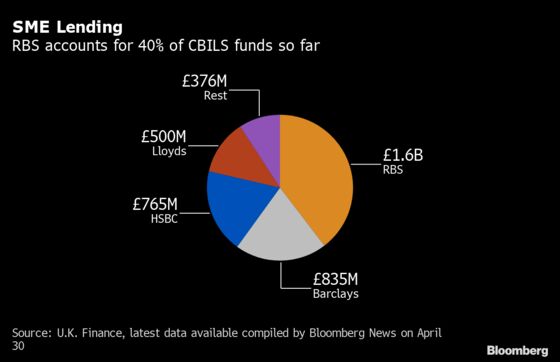

In the U.K., the onus has fallen squarely on the banks, especially the Big Four who dominate the market: HSBC, Lloyds, Barclays Plc and Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc. A chorus of voices ranging from business trade groups to senior officials of the Bank of England have implored them to cut through red tape and throw a lifeline to small and mid-sized enterprises, which contribute half of the country’s gross domestic product. On Monday, members of the Treasury Committee in the House of Commons will quiz senior executives from the lenders on their response to the lockdown.

Yet CBILS’s problems run deeper than overwhelmed call centers and clunky technology. British companies are going to need at least 40 billion pounds in emergency funds in the next few weeks to survive, according to Fideres Partners LLP, a London-based provider of financial analysis to regulators and law firms. The government’s assumption that the banking industry, which was largely bailed out by taxpayers in 2008, would step up and deliver is now being tested.

And yet Rishi Sunak, the chancellor of the exchequer, may not have helped matters by opting to partially guarantee loans rather than use the public purse to fully back them. That’s not only added complexity to the process, it’s also spurred the banks to use their traditional underwriting approach to handling applications.

“The U.K. was slow to learn the lessons from other markets and the need for speed, simplicity, and higher guarantees for the smallest firms,” said Huw van Steenis, a former senior advisor at the BOE who is now at UBS Group AG.

Just getting a handle on CBILS’s progress has been a chore. For the last two weeks the Treasury Committee, which oversees the financial services industry, has been asking U.K. Finance for daily data on applications and approvals. But the bank lobbying group has declined the requests, arguing that providing it risked the dissemination of “inaccurate commentary” about the program. The extraordinary dust-up shows no signs of abating as Mel Stride, the Conservative chairman of the committee, sent a second letter on April 30 stating that the information is essential to Parliament’s oversight work on the program.

In the meantime, banks may be taking a hardball approach in a time of national emergency. The Finance & Leasing Association, which represents non-bank finance companies, says it’s been receiving complaints from its members that some lenders are directing companies to delay or stop servicing existing debts if they want to qualify for CBILS loans. Innovate Finance, a group that serves fintech firms, is also fielding similar protests from its members, said Charlotte Crosswell, its CEO. Both organizations have notified officials at the Treasury about the concerns.

“There is clearly a problem here,” said Simon Goldie, the head of asset finance at the FLA, which has 166 members. “This is something that wasn’t the intention of CBILS and we would like to see this changed.”

Anna Stephens, a spokeswoman for RBS, said “we are seeking that customers do seek forbearance from other lenders but we are certainly not asking customers to default on other loans.” Lloyds spokesman Ian Kitts said, “We do not require borrowers to seek forbearance from their other financial providers as a condition of agreeing a CBILS loan.”

An HSBC spokeswoman said this wasn’t the bank’s policy and that it is working with its customers to deliver the best outcome for them. A spokeswoman for Barclays declined to comment.

Smaller lenders’ struggles to get up to speed have also held back lending. Haydock Finance Ltd. in Blackburn, England, has been so overwhelmed by requests to grant clients “repayment holidays” that it simply didn’t have the bandwidth to handle CBILS applications. Arranging such delays involves loads of due diligence and Haydock has to loop in its wholesale funder on decisions, said Andy Taylor, sales director. Even though the firm has been an approved CBILS lender since the program started on March 23, it only started accepting applications last week.

“We had to take care of the needs of our existing customers first and we have 6,000 live agreements so that was a huge piece of work,” Taylor said.

Given the economic stress of the pandemic and the scale of the government’s response, it’s no surprise that CBILS was going to have some growing pains, said Keith Morgan, Chief Executive Officer of the British Business Bank, the state-backed organization that’s administering program. Sunak, working closely with Morgan and U.K. Finance CEO Stephen Jones, is adjusting the program on the fly as problems arise.

“We are open to making refinements to enhance performance,” Morgan said. "We are seeing momentum build." In the seven-day period ending April 30, the number of CBILS loans increased more than 50% over the prior week.

Jones declined to comment on this story, and said in an e-mailed statement that“the banking and finance sector recognizes the role we must play in getting the country through these tough times, and staff are working incredibly hard to get money to those viable businesses that need it.”

Even so, critics have been urging the government to reboot the program with a 100% guarantee to free banks from time-consuming credit checks. Sunak will now give provide lenders with a full backstop on loans of less than 50,000 pounds in a new effort called the Bounce Back Loans program.

It’s no small irony that the government is now depending on the big banks to save SMEs. Large lenders have been ceding the low-margin market for small-business finance to newcomers such as Metro Bank Plc and Funding Circle Holdings Plc as they sought to strengthen their balance sheets and bolster profits. The shift has spurred the government to jump into the breach -- the British Business Bank was founded in 2014 primarily to support smaller ventures in lieu of commercial lenders.

This change means the big four are less able to serve SMEs in a crisis, said Alberto Thomas, the co-founder and partner of Fideres, the consulting firm.

“Banks are not going to risk their balance sheets in a situation like this,” Thomas said. “Now I fear there’s a whole wall of insolvencies coming.”

The banking industry counters that it’s just doing its job. Lenders not only have to manage their 20% exposure on CBILS loans but they also have to assess the total risk of the debt “on the government’s behalf,” U.K. Finance’s Jones told the Treasury Committee on April 15. While banks want to help enterprises weather the crisis, Jones said the message from Sunak is clear -- not every business will survive.

“Ultimately, banks are lending depositors’ money, so unless there is a measure of support for greater risk appetite and trying to get the money back at the end of the crisis, they cannot lend to businesses that they perceive to be likely to fail through the crisis,” Jones testified.

A Treasury spokesman said officials have been working with banks since this crisis began to ensure its programs work as best as possible for lenders and business, and that hundreds of thousands of firms across the country have received support.

But the Darwinian nature of the rescue push raises the possibility that the damage of the pandemic and lockdown will be worse than it should be. BOE Governor Andrew Bailey has said policy makers will have to make a judgment on the risks of economic scarring at Thursday’s policy decision.

As the wheels of government spin in Westminster, Yvonne Lin is still laboring to save Zelle Studio in London’s trendy Soho district. She said HSBC finally did approve an overdraft facility that amounts to about 30% of the loan she sought, but it took two weeks for her to be able to access the money.

“I took what I could get,” she says. “It’s really just about survival.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.