The Taper That Will Really Bite Into U.S. Growth Isn’t the Fed’s

In the coming Year of the Taper, it’s the fiscal version that will really bite.

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

In the coming Year of the Taper, it’s the fiscal version that will really bite.

The chatter in U.S. financial markets is all about the Federal Reserve’s yet-to-be-announced reduction of its bond purchases. That’s obscuring something important: the already-under-way cutback of the federal government’s budgetary support -- which is likely to have a much bigger impact on economic growth next year.

The U.S. expansion looks set to slow sharply in the second half of 2022 as measures that propped up the economy during the pandemic -- from stimulus checks for households to no-cost financing for small companies -- fade from view.

That will be the case even if President Joe Biden manages to win Congressional approval for the bulk of his $3.5 trillion Build Back Better agenda. The spending will stretch over years, with limited impact in 2022. It will also be at least partly paid for by tax increases that slow the economy down rather than speed it up.

‘Moves Sideways’

“We’re in for some very low growth rates” in late 2022 and into 2023, said Wendy Edelberg, director of the Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project. “It wouldn’t surprise me if there’s a quarter here or there where the economy basically moves sideways.”

She’s not alone in forecasting a steep slowdown. Jan Hatzius, chief economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., expects the U.S. to be expanding at a 1.5% pace by the end of next year, down from 5.7% over the course of 2021.

The coming deceleration would be unwelcome news for investors, who have bid up stock prices to record levels.

It could also spell trouble for Biden and his fellow Democrats in Congress, as they seek to retain slim majorities in November 2022’s mid-term elections -- especially if it’s accompanied by a rise in unemployment, though most economists don’t expect one.

There is a potential benefit: lower inflation. Prices have surged this year on the back of snarled supply chains and fiscally-fueled consumer demand. “We’ll need to come off the boil,” Edelberg said, because the rapid U.S. rebound will push the labor market and the economy to their limits by the middle of next year.

‘Wildly Overstated’

Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues are expected to discuss taper plans at this week’s policy meeting. Powell has said they could begin scaling back bond-buying this year. The central bank will still be providing the economy and financial markets with stimulus until the purchase program ends, likely sometime in 2022.

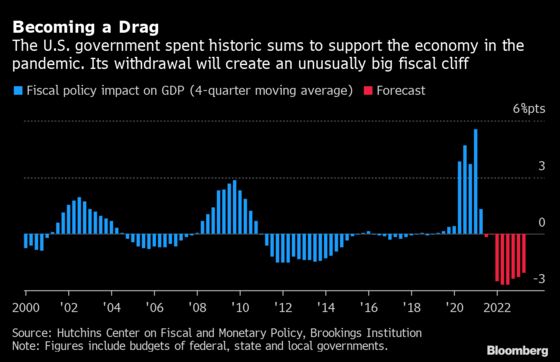

Not so with fiscal policy, which has already begun to act as a drag. The Brookings Institution’s Hutchins Center calculates that the economic impact from federal, state and local-government taxes and spending turned negative in the second quarter and will remain that way into 2023.

And even if Biden gets all the additional expenditures he’s seeking, the contractionary swing in the federal government’s budget balance over the coming year will still be one of the largest on record, White House figures show.

There are some mitigating factors.

U.S. households boosted their savings in the pandemic by some $2 trillion or more. That “cushions any so-called fiscal drag that might appear to be on the books,” said former CBO Director Douglas Holtz-Eakin, who is now president of the American Action Forum. He’s skeptical that budget swings will slow the economy dramatically, calling the idea “wildly overstated.”

State and local governments also have been slow to spend some of the help they’ve gotten from Washington, leaving them with firepower for the future.

‘Running for the Door’

But none of that is likely to fully offset the contractionary impact from fading budget support.

“The tailwind from fiscal policy is now beginning to turn into a headwind that is going to blow very hard by spring of next year,” said Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi. “Without any additional fiscal support the economy will feel a bit fragile toward election day 2022.”

Investors, for their part, are starting to fret about a coming slowdown. They turned markedly less optimistic about the economic outlook in Bank of America’s latest global fund-manager survey, entitled “Fiscal Frenzy Flips to Fiscal Flop.”

At the same time, they’ve remained all-in on equities. That disconnect leaves stock prices vulnerable, said David Jones, director of global investment strategy for BofA Securities.

“The longer this dissonance between the fundamentals and the positioning lasts, the more it raises the specter of a violent, disorderly market event in which everyone is running for the door,” he said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.