The Problem With Pinning All Your Market Hopes on Rate Cuts

The cure for the coronavirus is unlikely to come from a central bank.

(Bloomberg) -- The cure for the coronavirus is unlikely to come from a central bank, but equities accustomed to 11 years of Federal Reserve support are acting like it might.

U.S. stocks rallied the most in 14 months on bets that Group of Seven central bankers will coordinate a policy response to the outbreak that is threatening to derail the global economy. Anyone who’s watched the Fed jump start markets with an array of policy prescriptions over the years can be forgiven for pushing equities higher Monday. But a growing cohort worry the boost, while warranted, will be short-lived.

Easier monetary policy won’t lift travel restrictions or stop event cancellations that are starting to slow economies around the world as governments move to contain the virus’s spread, the concern holds. Outside of possible central-bank intervention, the virus news worsened Monday with more U.S. deaths, further travel restrictions and a surge in new cases.

“How would a rate cut or two get people to fly again? How would a rate cut reopen Chinese factories?” said Peter Boockvar, Bleakley Advisory Group’s chief investment officer. “If anything, it could do damage as it hurts bank profitability.”

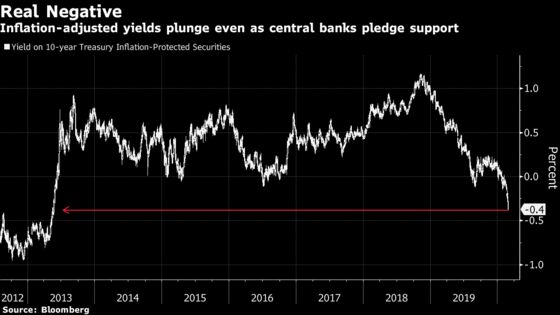

Risk assets were hammered last week amid growing concern over the outbreak’s economic impact. The S&P 500 Index plunged 13% from its record. A global rush for cover sent benchmark 10-year Treasury yields to an all-time low of 1.02% earlier Monday, and cracks in credit markets rattled nerves.

The S&P 500 ended Monday 4.6% ahead of Tuesday’s teleconference. However, a trio of bad news awaited after the close: Hyatt Hotels withdrew its 2020 earnings outlook, while Visa and Microchip Tech cut their earnings projections.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell calmed investors Friday when he issued a rare statement that the central bank stood ready to “act as appropriate” to support the economy. And equity futures surged on Sunday night as calls for easing mounted, with Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists saying that the Fed may act before its official gathering.

But snapbacks from market sell-offs are not uncommon, and this one owes a little to the velocity of last week’s rout -- it surpassed all others when stocks began the drop at all-time highs. Technical measures showing stocks were oversold flashed buying signals. In short, the selling had to stop somewhere.

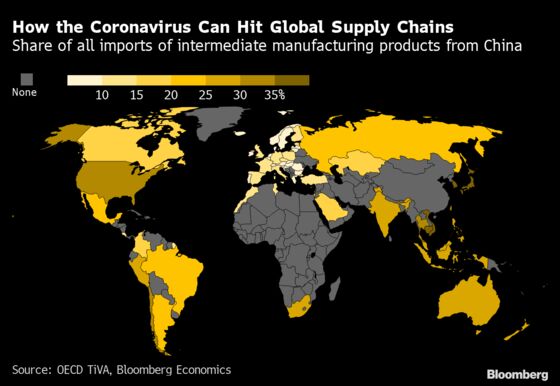

That’s left investors focused on what exactly the rate cut will do for markets. It may alleviate rapidly tightening financial conditions, but it’s unclear what effect it might have on disrupted supply chains, leaving corporate profits vulnerable, according to Paul Markham.

“The positive reaction that would occur is likely to be very short-lived,” said Markham, global equity portfolio manager at Newton Investment Management. “Given the fact that it’s going to be less impactful on those supply blockages, it wouldn’t necessarily be that positive from a fundamental standpoint.”

There’s some evidence that supply shocks are already hitting the U.S. economy. The Institute for Supply Management index slid to near-stagnation territory in February, suggesting that global supply chain issues are impacting the manufacturing industry.

Not everyone agrees that a Fed rate cut would be a futile exercise. Easing policy could fuel a wave of mortgage refinancings similar to that seen after the Fed lowered rates three times in 2019, according to JPMorgan Asset Management Chief Investment Officer Bob Michele.

“I bristle when people say cutting rates can’t do much here,” Michele said in a Bloomberg Television interview. “It does help the consumer refinance, and then the consumer could spend some of those savings.”

In the eyes of Peter Tchir at Academy Securities, monetary policy is too blunt an instrument to address the outbreak’s economic ripple effects. Targeted fiscal policy -- such as tax cuts -- would be better suited to aid globally exposed companies that need to rebuild their supply chains.

Additionally, the Fed runs the risk of running out of firepower should they cut imminently, Tchir said.

“They’ll cut, stocks will briefly rally and start selling off and if we wind up breaking through where we were when they cut, we’re going to be in far worse shape than had they not cut at all,” said Tchir, Academy’s head of macro strategy. “You’ve used your ammunition and didn’t get the result.”

Of course, central banks have other tools at their disposal other than merely lowering rates. While rate cuts alone may not change behavior, markets may perceive them as a precursor to more substantial stimulus, such as stepped-up liquidity injections or T-bill buying, according to PineBridge Investments’s Anik Sen.

“It is an indication to capital markets that the Fed stands ready to provide more monetary stimulus,” said Sen, global head of equities at PineBridge, which manages over $100 billion. “It’s not so much the cuts, but the injection of liquidity that is much bigger as a market mover.”

--With assistance from Liz Capo McCormick.

To contact the reporters on this story: Katherine Greifeld in New York at kgreifeld@bloomberg.net;Vildana Hajric in New York at vhajric1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeremy Herron at jherron8@bloomberg.net, Dave Liedtka, Brendan Walsh

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.