PBOC Is Trying to Fix China’s Decades-Old Credit Conundrum

China’s central bank is trying to fix one of the domestic economy’s most intractable problems.

(Bloomberg) -- China’s central bank is trying to fix one of the domestic economy’s most intractable problems: Poor access to credit by small companies.

Having resisted the kind of large-scale stimulus rolled out by its global peers, the People’s Bank of China instead has been tapping away at small-scale programs designed to improve the ability of small firms to survive the coronavirus slump. On Monday it announced its latest plan, using 400 billion yuan ($56 billion) to turn unsecured loans to businesses into one-year cash for banks.

While a large infusion of money or bond-buying would cheer markets who’ve been disappointed by the modesty of Governor Yi Gang’s stimulus effort to date, it would likely only end up in the coffers of big state-owned banks or government-run companies. The small firms that make 80% of urban employment have traditionally been starved of bank credit due to lack of collateral or a credit record.

“Yi Gang has been inventing new tools since he’s been in office, rather than using straightforward interest rate cuts and reserve ratios cuts for easing,” said Zhou Xue, an economist at Mizuho Securities Asia Ltd in Hong Kong. “It’s a process of trial and error. No one knows if the current approach can work, even the central bank, as it tweaks the policy while doing it.”

Small and micro-sized companies -- which the PBOC defines as firms with a credit line smaller than 10 million yuan -- had 11.6 trillion yuan of outstanding loans at the end of 2019. That’s a small fraction of the 153 trillion yuan of loans made by the entire banking sector.

The credit support plan unveiled on Monday builds on top of an older policy tool known as the re-lending program, which provides cheap base money to the financial system with a condition that the money can only be used for loans to specific sectors. A refreshed version of the scheme has been increasingly relied on since banks’ risk appetite vanished during the course of the coronavirus outbreak.

“If the PBOC just uses aggregate monetary policy to supply liquidity, the money will be grabbed by privileged sectors such as large state firms and local financing platforms, while small and private companies still can’t get enough financial support,” said Zhang Xu, head of the fixed-income research at Everbright Securities Co. in Shanghai.

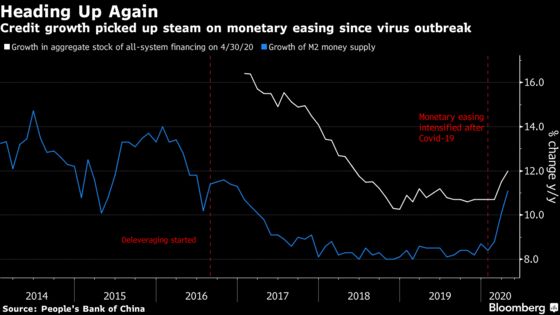

There are some signs that the strategy to date is working. Credit growth accelerated to 12% from a year earlier in April, significantly faster than the nominal expansion of the economy.

Economists have compared the PBOC’s new policy to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s Main Street lending program, the European Central Bank’s TLTRO program, and even quantitative easing. Others have reacted warily, doubting whether such a small program can change much at a time when the economy is facing its worst performance since the 1970s and unemployment is soaring.

“What’s eventually at stake is whether the fallout of the coronavirus would lead to a massive round of bankruptcies which in turn result in a systemic financial crisis,” said Lu Ting, chief China economist at Nomura Holdings Inc. in Hong Kong. “Extending help to banks especially small banks could alleviate these problems in the near term.”

PBOC Deputy Governor Pan Gongsheng said on Tuesday that the new program isn’t QE in either nature or scale. He also dismissed speculation that it could undermine the need to cut banks’ reserve ratios or interest rates. On Tuesday, the yield on 10-year government bonds reached its highest level since late February on market concern that the new policy would mean less stimulus from the central bank.

Effectiveness Doubts

Economists from Citigroup Inc. warned the tool could lead to greater risks in regional banks’ asset quality.

Wary of the debt bomb and wasteful investment created by China’s last round of mega-stimulus after 2008, officials this time are being deliberately conservative. The government has said there is room to scale up stimulus if needed, though it remains unlikely that a massive asset-purchase or rate-cutting program is around the corner.

“The PBOC is changing its playbook from old-style stimulus to a new one, but it hasn’t figured out a clear strategy yet,” said Liu Peiqian, a China economist at Natwest Markets in Singapore. “That’s why it’s stitching patches here and there, trying to close the loopholes while maintaining its overall stance of not flooding the economy.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg