The Metal That Started Trump’s Trade War

As recently as 2000, the U.S. was home to 23 aluminum smelters. Today there are six.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Working at the Century Aluminum Co. smelter in Hawesville, Ky., can be like having a job in an oven. The interior temperature hovers around 140F, which isn’t necessarily hotter than, say, your typical steel mill. What’s especially hellish about an aluminum smelter is how close you have to stand to bubbling vats of molten, electrified metal.

Workers wear helmets, masks, and heavy, fire-retardant clothing. They look like smoke jumpers. Over a 12-hour shift they’ll lose several pounds of water weight as they peer over cauldrons, occasionally stirring 1,700-degree liquid aluminum with long metal rods. They wear earplugs against the hum of 170,000 amps surging through the mixture, which chemically breaks down ore. The air itself feels charged—and smells like the blended aromas of an overheated car engine and a sweaty fistful of coins. If you breathe through your mouth, you can taste the metal on your tongue.

The Hawesville smelter makes some of the world’s highest-purity aluminum, and it’s the only one in the U.S. that mass-produces the military-grade kind needed for fighter jets and tanks. Yet the method it uses isn’t that different from how aluminum was made in 1886, when Charles Martin Hall, an Alcoa Corp. co-founder, first shot an electrical current through a mineral bath of aluminum oxide. The process has become more efficient over time, but no one’s figured out a better way to separate oxygen atoms from aluminum atoms. The business is stubbornly dirty, expensive, and dependent on human labor.

It’s also incredibly energy-intensive. At full capacity, the Hawesville plant uses as much electricity as the entire city of Louisville (population 620,000), about 70 miles away. Not that the plant is at full capacity these days. This smelter was built in 1969, on the banks of the Ohio River, in a region that used to be the aluminum industry’s equivalent of Silicon Valley. Cheap coal dug out of the Appalachians and barged down the river was used to power half a dozen smelters clustered around Kentucky, Ohio, and Western Pennsylvania.

As recently as 2000, the U.S. was home to 23 aluminum smelters. Today there are six. Aluminum companies decided a long time ago that it was cheaper to produce the raw metal in areas outside the U.S. that had easy access to cheap hydro, thermal, and petroleum power—Canada, Iceland, Russia, and the Middle East. As aluminum became less expensive to make elsewhere, American companies focused on more profitable products made with low-cost imported raw ingot.

That’s been great for companies that use the metal: carmakers, airplane builders, brewers (all those cans), and aluminum sheet manufacturers. But the smelting business in the U.S. has been crushed, shedding two-thirds of its jobs over the past five years. Of the remaining smelters, Century owns three, including Hawesville. As aluminum prices sank, so did Century’s profits, to the point that by the end of 2015 the entire U.S. smelting industry was on the brink of extinction. Century lobbied the government and laid off about a third of its workers as its U.S. plants inched toward oblivion. Then Donald Trump got elected, and everything changed.

In March 2018, Trump fired the first major shot of his international trade war when he announced a 25 percent tariff on foreign steel and 10 percent on aluminum. The result has been chaos on both fronts, but particularly with the latter. The U.S. still produces two-thirds of the steel it uses, but it imports 85 percent of its raw aluminum. Through Sept. 19, companies have had to pay $625.4 million in aluminum tariffs, as they can’t find enough domestic supply. Canada has retaliated with its own tariffs. Since a piece of aluminum can take as many as five round trips across the U.S.-Canada border on its journey from ingot to finished product, what used to be the free passage of goods between two friendly nations has become an expensive logjam.

MillerCoors LLC says the tariffs will cost it $40 million in profit this year. Coca-Cola Co. is raising prices. Ford, General Motors, and Boeing have all said this is bad for business. So does most of the U.S. aluminum industry: Alcoa lowered its profit forecasts; trade groups claim that by trying to save low-margin smelters, Trump will hurt the more profitable segments of the business, killing more jobs than he creates.

There is one company that’s happy: Century Aluminum. On Aug. 22, at a ceremony celebrating the restart at the Hawesville smelter, Chief Executive Officer Michael Bless stood in front of about 100 of his workers, like a coach giving a speech after a come-from-behind victory. “Our country was within months of seeing an entire industry disappear,” he said from a makeshift stage.

A thin, bald man with glasses, Bless gave a tip of his cap to U.S. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross, who was sitting nearby as a sort of guest of honor. “Now, for the first time in decades,” Ross said, “we’re changing the trajectory of the entire aluminum industry. … This is a case of the U.S. government finally standing up for American workers, American families, and American national security.”

So how did this happen? How did Trump pass a tariff against the broader wishes of an industry he was claiming to protect? How did Century Aluminum, a midsize company with fewer than 2,000 workers, beat back practically every other company in America to help bring about one of the most dramatic changes in trade policy in a generation? Throughout Trump’s public campaign for aluminum tariffs, Century was front and center. Bless has been at Trump’s side at numerous White House events; his workers paraded on cable news as evidence of hardworking regular folks undercut by illegally subsidized foreign aluminum. The proceedings were wrapped in Americana and tinged with a Trumpian sense of victimization.

What wasn’t mentioned was that Century’s biggest shareholder is Glencore Plc, the Swiss trading company that is the biggest buyer and seller of commodities in the world. Century was spun out of Glencore in 1996. The Swiss company still owns about 40 percent of Century stock and has a seat on Century’s board. Most of the aluminum Century makes is sold to Glencore, which then resells it to buyers through its trading operation. According to a government filing by Century, Glencore accounts for 75 percent of Century’s consolidated net sales.

While Century was lobbying the Trump administration, Glencore, along with a handful of other commodity trading companies, was stockpiling record amounts of foreign aluminum in the U.S.—the idea being, if tariffs were announced, prices would rise, and all that cheap foreign metal would suddenly become more valuable.

And that’s what happened. When the tariffs went into effect, about 2.2 million tons of foreign aluminum was sitting in warehouses in the U.S., according to Harbor Intelligence, a market research firm. Glencore owned somewhere from 100,000 to 400,000 tons, according to four traders who asked not to be identified because they aren’t authorized to speak publicly. And when the tariffs went into effect? Boom—instant profit, in the tens of millions. Next year could be even more lucrative for Glencore and Century. A financial analysis by Bloomberg projects Century will enjoy record revenue in 2019. That will be good news for several hundred workers in Kentucky and South Carolina—and even better for traders in Zug, Switzerland.

Bless has been with Century for about 12 years. After getting an undergraduate degree in medieval history from Princeton University, he worked as an investment banker, doing deals at Dillon, Read & Co. in New York. He spent a few years as an executive at an electric motor manufacturer in Wisconsin and then joined Century as chief financial officer in 2006. Back then, aluminum smelting was a good business. Prices were up, and Century’s profits were growing at a double-digit annual rate. Nine years later, when Bless was CEO, the bottom dropped out.

By 2015, global aluminum production was far outpacing demand, thanks mostly to the continued rise of China’s smelting industry. Over several months, U.S. aluminum prices crashed more than 30 percent. The previous year, Congress held hearings meant to highlight a particular kind of commodity market manipulation. For years, banks and trading companies had been stockpiling metal in warehouses overseen by the London Metal Exchange, the largest metal bourse in the world. Traders would force customers to wait months to get crucial raw materials such as aluminum to create artificial scarcity and push up prices. After Congress intervened, the LME changed its rules, banning the practice. Metal poured out of warehouses around the country, adding to the glut already on the market.

Bless laid off hundreds of workers and shut down a third of Century’s U.S. production, including 60 percent of the output at Hawesville. He traveled from his headquarters in Chicago to his plants in Kentucky and South Carolina, begging his remaining employees to stay with the company while he figured out a solution. He tried to project optimism, but there was no denying that it was simply cheaper to make aluminum overseas. According to estimates from Harbor, for a U.S. smelter to be profitable, it has to sell a ton of raw aluminum for about $2,200; smelters in Russia, China, and the Middle East need $1,500 to $1,800. It wasn’t a matter of will, it was a matter of math.

Bless persuaded the Century board to put a few hundred thousand dollars into a public-relations and lobbying campaign to send out the equivalent of a mayday signal. That summer he invited every presidential candidate to tour his ailing plant in Hawesville. No one came. Not even Trump.

To Century, the main villain is China, which over the past 25 years went from having almost no aluminum smelters to producing about half the world’s supply, helped by cheap government-backed loans and subsidized electricity—violating World Trade Organization rules. On Halloween 2015, a public-relations firm Century hired put a mini-documentary about the Hawesville smelter on YouTube. The production is heavy with Ken Burns-style melancholy. As a lone violin plays minor-key folk tunes, workers talk about what the jobs meant to their families; the mayor talks wistfully of a bygone age of municipal glory; everyone laments how China cheats. “We make the purest aluminum in the world, and that ought to mean something to somebody,” says one worker.

In January 2017, about a week before Trump’s inauguration, the Obama administration initiated a WTO complaint against Chinese aluminum. But Trump had other ideas. To him, the WTO is just another inscrutable globalist bureaucracy full of America haters. Plus, he was never likely to take up an action Obama started. He wanted to go bigger and hit not just China but the whole world. He needed a bludgeon—and found one in a little-known provision of trade law. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 allows a president to restrict imports in the name of national security. It’s intended for times of war and has been used only a handful of instances—including in 1979, to embargo oil from Iran, and from Libya in 1982. Very few people in Washington had even heard of Section 232 before Trump invoked it.

A 232 tariff has the advantage of allowing a president to bypass the WTO. But there’s a catch: The administration must first investigate whether national security is truly at risk. And so, in April 2017, Trump announced an investigation into steel and aluminum imports. It was up to Ross, the Commerce secretary, to conduct hearings to figure out if imports could eventually force all U.S. smelters out of business and imperil America’s supply of military-grade aluminum.

In June 2017 industry groups gathered at the Commerce Department building in downtown Washington, a few blocks from the Trump International Hotel. Invitees were delighted that, at last, a president was willing to teach China a lesson. Manufacturers specializing in aluminum products were particularly excited, given the vast quantities of wheels, car bumpers, window frames, and other basic goods coming into the U.S. from across the Pacific. “We thought we could be a poster child,” says Jeff Henderson, president of the Aluminum Extruders Council, a Chicago-based trade group whose members manufacture about $17 billion worth of products each year.

The new-day-dawning atmosphere didn’t last long. Henderson and his industry peers quickly realized the administration wanted to talk about tariffs on just raw materials, not on higher-value items the U.S. makes. That would mean rising prices for most of the industry, since, again, about 85 percent of raw aluminum is imported. At one point there was talk of tariffs as high as 30 percent on foreign-made aluminum, which would have been devastating to Henderson’s members. For six months, Henderson went back and forth between Chicago and Washington, pleading with administration officials to listen to reason. “We felt completely ignored,” he says. “It was clear they were listening to one company and one company alone, and that was Century.”

Jorge Vazquez, the founder of Harbor Aluminum, provided research and input for the Commerce investigation. “The outcome, clear and simple, was not rational,” he says. “The Commerce Department, it seems, basically heard Century and only Century. The Aluminum Association was against this, the Council of Extruders was against it, end users were against it, independent experts were against it, the DOD was against it—even the president’s economic advisers were against it. Only Century’s view prevailed.”

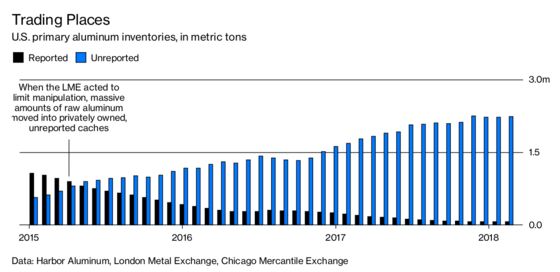

According to Vazquez, Commerce officials were wildly wrong about the state of U.S. aluminum supplies. The administration insisted that the U.S. was dangerously short of raw aluminum, when in fact there was a record amount stored around the country. The problem was that Commerce staffers were relying on data from the London Metal Exchange and Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which oversee a vast network of warehouses. But that’s not where the aluminum was.

After Congress got involved and the LME changed its warehousing rules in 2015, taking away the incentive for banks and traders to hoard metal in exchange-owned warehouses, most of that metal went into private stockpiles owned by trading companies such as Glencore. By July 2017, when Commerce staffers viewed data from the exchanges, on paper it looked like there were only 120,000 metric tons of primary aluminum in supply, when there were more than 2 million tons. Some of it was sitting right out in the open.

One of the biggest stashes in North America is just outside New Orleans. About 10 miles southeast of the French Quarter, along a bend in the Mississippi River, a trading company named Castleton Commodities International LLC has turned a swampy field into a glinting pile of aluminum—500,000 tons, worth more than $1 billion. It’s so big it’s visible from space. Vazquez says he sent reams of data to show Commerce staffers the extent of the stealth inventories in the U.S. “They didn’t want to hear it,” he says. “Their focus was to make sure that the five remaining smelters were able to survive. Nothing else was important.”

The Commerce Department says it consulted a “wide array of stakeholders and experts in conducting the investigation.” It received 91 written public comments and held a public hearing at which 31 people, including Vazquez, testified.

At around 6:30 a.m. on March 1, Bless was on an elliptical machine in a hotel gym in Washington when his cellphone rang. He didn’t recognize the number and considered not answering. He’s glad he did. It was Ross, asking whether Bless could come to the White House that day.

A few hours later, Bless was in the Cabinet Room along with a dozen other steel and aluminum executives, many of whom had flown in that morning. No one had been told exactly why they were there. As they sat and waited, an epic fight was raging in the Oval Office.

For months, White House officials had been fiercely debating whether to issue tariffs on steel and aluminum. That fight was now coming to a head. Then-National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin had been urging Trump to reconsider or at least slow down, telling him that taxing raw aluminum would create some jobs but would likely destroy many more. Ross and trade adviser Peter Navarro urged Trump to stand firm.

Lost in all this was a memo that U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis had sent to Trump and Ross a week earlier. While agreeing that there were unfair trade practices that pose a risk to national security, Mattis pointed out that military requirements for steel and aluminum represent only about 3 percent of U.S. production. “Therefore,” he wrote, “DOD does not believe that the findings in the reports impact the ability of DOD programs to acquire the steel or aluminum necessary to meet national defense requirements.” In other words, there’s no national security concern here, so please don’t upend global trade for the sake of a few truckloads of aluminum and steel.

Finally, just after noon, Trump ambled into the Cabinet room. Then the press came in. The president gave a quick speech filled with his familiar talking points of “terrible trade deals,” U.S. companies being “horribly treated,” and the “disgraceful” state of U.S. industry. Almost as an afterthought, when prompted by reporters, he announced the specifics: 25 percent on steel, 10 percent on aluminum. Within a week, Cohn resigned, and the cost of aluminum in the U.S. shot up.

Ross went on TV to play down the rise in aluminum prices. It’s just a few cents for a can of soup or beer, he said on CNBC. But to people like Henderson the tariffs have been a disaster and, in fact, accomplish the opposite of what they claim to do: By making the metal more expensive in the U.S., they give an implicit cost advantage to all those overseas wheel, car bumper, and window frame makers, and every other foreign company that manufactures things out of aluminum. “This is the most self-destructive trade act I’ve ever seen,” Henderson says.

To Bless, such complaints are just whining from a portion of the industry that’s luxuriated in illegally subsidized raw material for too long. He doesn’t see more expensive aluminum noticeably raising prices for consumer goods. When aluminum prices fell 40 percent in 2015, he rhetorically asks, “Did the price of the aluminum in your car that you wanted to buy or in that famous beer can go down by 40 percent? Did you get a rebate from Molson Coors and Coca-Cola and all those great guys whose products I consume and enjoy? Did you get an aluminum rebate when you went to your Ford dealer? Are you going to not buy your, you know, Ford or Chrysler? Come on. Really? The price of a 777 goes up by $20,000 on a $250 million list price.”

Bless also vehemently disagrees that Trump’s tariffs amount to protectionism. “It’s reciprocity,” he says. “Yeah, that’s it. And the U.S. industry, as we’ve said screaming from the rafters, isn’t supported by a state entity. All we’re trying to do—all the government is trying to do is say this is critical for the U.S. economy, national security.”

As for the notion, widespread among people in the aluminum industry, that the big winner here is Glencore, Century’s largest shareholder, Bless flatly denies that, too. He says it’s all a conspiracy theory. (Glencore declined to comment for this article.) Asked what Ivan Glasenberg, Glencore’s CEO, thought of the idea of tariffs, Bless says the topic hasn’t come up. “Never talked with Ivan about it,” he says. “He doesn’t sit on our board.” Which is true; Glasenberg himself isn’t on Century’s board—one of his employees, a financial analyst and asset manager named Wilhelm van Jaarsveld, is.

But really: Bless and Glasenberg never talked about this? “One hundred percent, never,” Bless says. “Yeah, I would never talk to Ivan—I don’t talk to Ivan, other than when he calls and says, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’ ”

Bless gets a bit defensive with the Glencore questions, but otherwise he sounds a long way from crisis mode. Century says it plans to invest $150 million in its U.S. smelters this year and increase its total production by 35 percent. Overall, U.S. aluminum production is forecast to rise from about 740,000 tons to more than 1 million in 2019, Harbor says.

But markets have a way of taking unexpected turns, and at least one side effect of the tariffs could become a problem for Century. Earlier this year, China retaliated by putting a tariff on aluminum scrap from the U.S. The 232 tariff doesn’t cover scrap, which has led to more scrap coming into the U.S., which to manufacturers is a perfectly good substitute for raw aluminum smelted from ore. And as a further result, companies are already choosing to buy less expensive scrap and canceling contracts to buy aluminum. If that keeps up, over the next several years the scrap market could cannibalize much of the smelting capacity that’s expected to restart. Which would leave Century, and its workers, right back where they began.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jim Aley at jaley@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.