How the Fed Is Bringing an Inflation Debate to a Boil

The Great Inflation Debate touches every area of policy and everyone has an interest in the outcome.

(Bloomberg) -- There’s hardly any question that carries greater weight in economics right now, or divides the financial world more sharply, than whether inflation is on the way back. One camp is convinced that the no-expense-spared fight against Covid-19 has put developed economies on course for rising prices on a scale they haven’t seen in decades. The other one says the virus is exacerbating the conditions of the past dozen years or so -- when deflation, rather than overheating, has been the big threat. A decision by the U.S. Federal Reserve to allow inflation to run higher during economic recoveries is raising the stakes in the debate.

1. What’s at stake?

Governments and central banks may face pressure to curtail their pandemic relief efforts, already worth some $20 trillion according to Bank of America, if they trigger a spike in prices. Workers and consumers will see the impact in wage packets and household bills. More than $40 trillion of retirement savings is at risk of erosion if inflation returns. Inside the economics profession, there’s something else at stake too. Charles Goodhart –- a scholar at the London School of Economics who, at the age of 83, has seen a few orthodoxies rise and fall –- argued in a recent paper that what happens to inflation after the pandemic “will affect macroeconomic theory and teaching, perhaps forever.”

2. What is the Fed doing?

Switching from what’s known as inflation targeting to inflation averaging. Fed Chair Jay Powell said the Fed will seek inflation that averages 2% over time, a step that implies allowing for price pressures to overshoot after periods of weakness. The U.S. economy has rarely reached the inflation target of 2% since the Fed formally adopted it in 2012. The practical effect of Powell’s announcement was to signal to markets that the central bank will move very slowly to raise interest rates from their near-zero level as the economy recovers from the damage caused by the coronavirus pandemic.

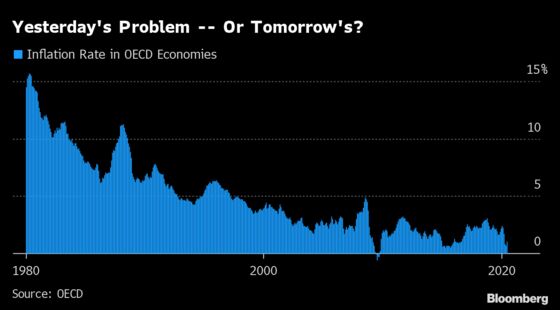

3. What’s the evidence on inflation?

For now the jury is out. Some countries reported a drop in prices early in the crisis, and a jump more recently. In the bond markets and among consumers, measures of expected inflation have edged higher. But the data that will ultimately settle the question could take years to trickle in. In the meantime, investors and the public are left to weigh the arguments. Here are some of the main ones.

Case for Inflation: Money Supply

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, the free-market economist Milton Friedman famously argued. That’s still a widely held view. And those who hold it are pointing to the wave of money created by governments to fight the pandemic –- and predicting that sooner or later it will wash through the whole economy and push prices up. In many countries, money supply is growing at some of the fastest rates on record. What’s more, unlike a decade ago, when a similar infusion of money never moved much beyond banks’ balance sheets, there are signs this time around that the cash is making its way into the pockets of consumers and companies.

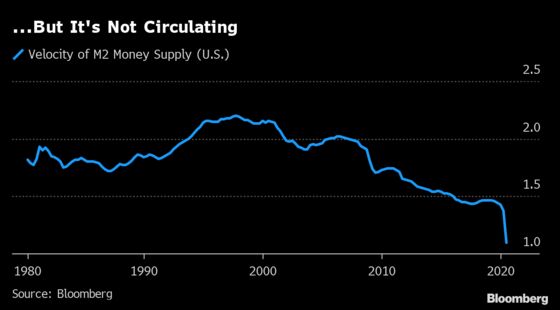

Case Against: Money Velocity

It’s the use of money, not just its creation, that affects prices. That’s one explanation for subdued inflation since 2008, even as central banks cranked up the printing presses. And the same forces may still be at work. In the U.S. the “velocity” of money -– the frequency with which it changes hands, as people use it to buy goods and services -– fell off in the 2008 financial crisis, never really recovered, and has collapsed to unprecedented lows now.

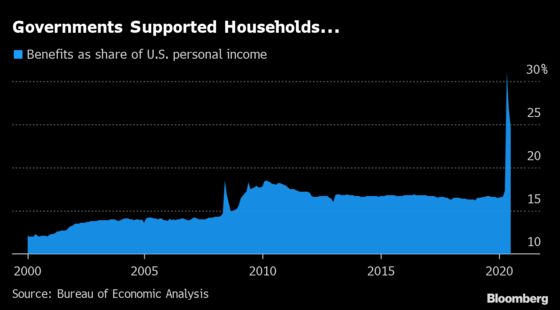

Case for Inflation: Household Wealth

Spending may bounce back faster than it did after 2008, and drive prices higher, because a more aggressive policy response has cushioned the blow to household finances. Propped up by central banks, stock markets have taken months instead of years to recover. Home prices didn’t take much of a hit. And lower down the income ladder, governments have provided substantial support to workers who got furloughed or fired. Fiscal stimulus, unlike the monetary kind, goes directly into people’s bank accounts -– where it’s likely to get spent.

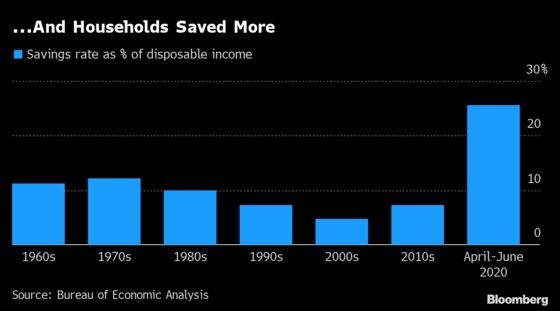

Case Against: Household Fear

Incomes may have held up through the recession, thanks to government intervention, but not all the money is getting spent. Savings rates have soared. To be sure, that’s partly a function of lockdowns that left restaurants and bars shuttered, and air travel widely shunned. But even as economies reopen and consumers have more options, worries about health and work could mean they stay cautious.

Case for Inflation: Loose Central Banks

One reason why many analysts expect higher inflation is simply because central banks, the guardians of price stability in the low-inflation era, are more willing than ever to let it rise, a trend emphasized by the Fed’s announcement of its new strategy. The Fed’s focus is on “the disinflationary aspects of the current shock,” says Bank of America’s Bruno Braizinha. Even before any official change in the policy stance, it’s already “committing to keeping rates low for the foreseeable future.” The European Central Bank has embarked on a similar review. Accommodative monetary policies have been tried before in the campaign to gin up some inflation, and fallen short. What’s new, according to Morgan Stanley economists, is that “central banks are now committing to make up for some of the lost inflation during downturns.”

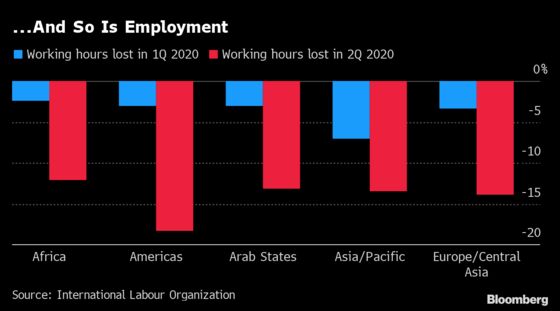

Case Against: Loose Labor Markets

Policy makers have worked with a rule of thumb that assumes some kind of trade-off between inflation and unemployment, known as the Phillips Curve. The idea is that prices will only face sustained upward pressure when the economy is using all its resources –- including labor. Doubt has been cast on the strength of that link. Still, if there’s any connection at all, then it should ease concerns about inflation. Employment everywhere has slumped, with little prospect of a quick rebound to pre-pandemic levels.

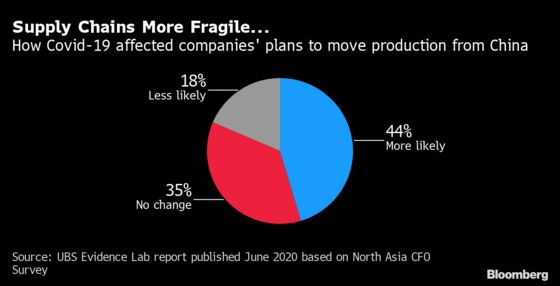

Case for Inflation: Supply Shocks

There’s already evidence that disruptions to supply chains are pushing prices up. In China, for example, food inflation has been accelerating in the last couple of months, and a squeeze on imports because of the pandemic is one reason why. The long-run risk is that the virus will escalate tensions like the ones behind the U.S.-China trade war. Governments may become more reluctant to rely on other countries for strategic goods, such as masks and medicine or computer chips. They could pressure business to bring manufacturing home, even when it’s more expensive. “Trade, tech and titans” -- cheap imports, technological advances and corporate giants with the market power to suppress wages -- have been “the driving forces behind the disinflationary trends over the last 30 years,” Morgan Stanley economists wrote. But the same trio also gets blamed for widening inequality, and faces growing political scrutiny that “could create a regime shift in inflation dynamics.”

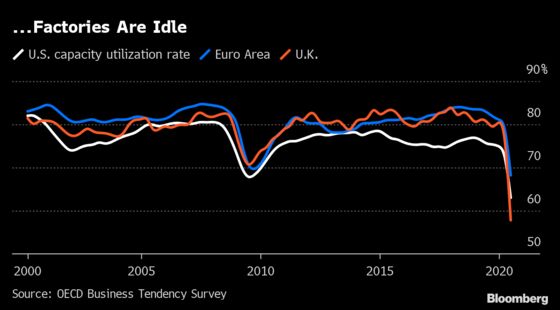

Case Against: Spare Capacity

The fight against Covid-19 has often been compared with an actual war, the kind of disaster that historically has triggered inflation. But there’s an important difference. Military conflicts wreck the supply side of the economy, like factories and railway lines, leading to bottlenecks and shortages that push prices up. The coronavirus has left those facilities intact -- even if they’re not being used right now. In a pandemic, it’s demand that takes the main hit, says Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief Asia Pacific economist with Natixis SA. “Capital is not destroyed or depleted, so it is much easier to end up with excess capacity,” she says. That distinction is one reason she’s “in the deflation camp.”

The Reference Shelf

- Fed Chair Jay Powell’s speech outlining a new approach to inflation.

- Charles Goodheart’s essay on how the pandemic will alter economic thinking about inflation.

- The European Central Bank’s summary of its monetary policy response to the coronavirus.

- An essay by Milton Friedman on monetary policy and inflation.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.