The Gold Vault That Floods in Netflix’s Casa de Papel? It’s Real

Spain’s central bank really does have a chamber in its vault that floods with water if bullion raiders should happen to break in.

(Bloomberg) -- When a bandit in the Netflix series La Casa de Papel dons snorkeling gear to swim through a flooded gold vault in the Bank of Spain, the stunt seems worthy of a James Bond villain.

But what looks like a far-fetched TV plot is actually based on real-life security defenses in place at Spain’s central bank.

The Madrid-based institution really does have a chamber in its vault that floods with water if bullion raiders should happen to break in. And that’s only one of the obstacles placed in the way of would-be thieves.

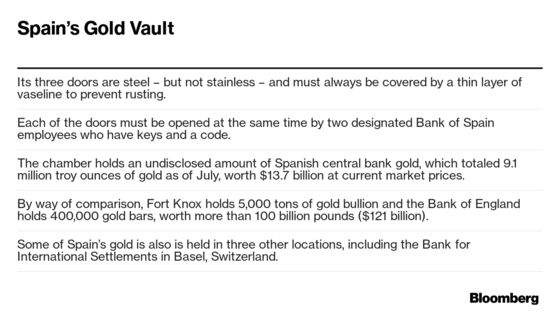

The robbers in the third season of La Casa de Papel -- known as Money Heist in English -- break through one armored door to reach the gold. In reality, there are three steel doors.

The first and biggest weighs 16.5 metric tons (18.2 U.S. tons). It fits so perfectly into its frame that the Bank of Spain says even a piece of fluff will prevent it from sealing shut. The portal then leads to a 35-meter (115-feet) elevator shaft down to an ante-chamber that leads across a retractable drawbridge to a second armored gate.

It’s that space which would flood if real-life robbers were to break through the first door and activate the security system.

Since construction of the gold vault finished in the mid-1930s, there has never been an “attempt to enter without authorization,” the Bank of Spain says.

The folklore that’s built up around the vault proved irresistible to the makers of La Casa de Papel and its fans. More than 34 million households have seen at least some of the episodes from the third season since it launched in July, a spokeswoman for Netflix said in an email.

In the first two seasons, La Casa de Papel’s band of raiders storm Spain’s Royal Mint to print millions of euros. In the third season, they target the Bank of Spain for its gold and to pressure authorities to release one of their imprisoned gang members.

Angry protesters gather outside the central bank at the urging of the gang’s mastermind, El Profesor, who asks Spaniards to show up en masse to back what he calls their “resistance.”

There’s a grain of truth to the anger reflected in those scenes. Many Spaniards still resent the Bank of Spain for its failure to crack down on lenders and their go-go lending standards, which helped fuel a property boom that turned to bust.

Some of that resentment has faded amid a robust economic recovery and Bank of Spain Governor Pablo Hernandez de Cos is working to improve the institution’s reputation.

Unlike in the Netflix series, the governor doesn’t have five paramilitary-like body guards. And the scenes that the series portrays as taking place at the Bank of Spain in Madrid were actually shot about 3 kilometers (1.9 miles) north of the central bank at the Ministry of Public Works.

In an era of cyber-attacks conducted from the laptops of anonymous hackers, there’s something almost quaint about a series that focuses on physical barriers to gold heists such as water traps.

“Back in the 1930s, there was no CCTV, there was no remote monitoring, there were no seismic sensors,” Seamus Fahy, CEO of Merrion Vaults in Dublin, said. Fahy says he’s visited hundreds of vaults in his search to rent or buy them from banks that are closing down.

By definition, the steps taken by governments to protect the world’s gold remain mysterious. As the U.S. Mint says of its storied facility at Fort Knox, “perhaps the most advanced system the Depository has to offer is its secrecy.”

Even so, the Bank of Spain’s precautions sound unusual, said Fahy. “I’ve never seen an ante-chamber that floods,” he said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeannette Neumann in Madrid at jneumann25@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Fergal O'Brien at fobrien@bloomberg.net, Charles Penty, Paul Gordon

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.