The Fed’s Future Is Already Here as U.S. Joins Zero-Rate World

In the second emergency interest-rate cut in two weeks, the Fed slashed its benchmark back to essentially zero.

(Bloomberg) --

America’s central bankers thought they had plenty of time to prep for their next encounter with the zero-rate world they escaped with such difficulty after 2008.

On Sunday night, the coronavirus plunged them back into it well ahead of schedule.

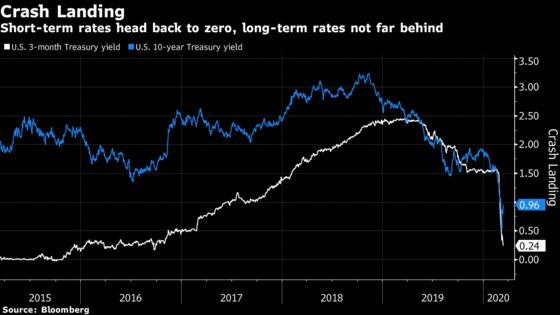

In the second emergency interest-rate cut in two weeks, the Fed slashed its benchmark back to essentially zero and announced a massive program of bond-buying. It was the latest attempt to save an 11-year expansion from the pandemic, which has wreaked havoc across financial markets and threatens to tip the U.S. into recession too -- if it hasn’t done so already.

It’s all a far cry from the “Fed Listens” tour that Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues announced in late 2018, when the economy was growing at a healthy clip and looked set to keep doing so. The goal was to gather ideas from business leaders and the general public about how monetary policy could be improved.

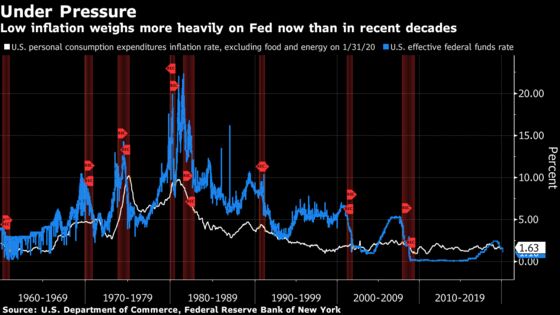

Lurking in the background all along was an uncomfortable thought. The Fed, so central to the country’s strategy of managing business cycles, may no longer be well-equipped to deliver its mandate of maximum employment and stable prices on its own.

Zero, Then What?

That idea has gained strength during the coronavirus emergency, when Fed interventions haven’t been able to arrest the gathering rout on markets -- a pattern that repeated late Sunday as U.S. stock futures hit limit-down.

“The Fed doesn’t really have the scope to do what it needs to do,” said Narayana Kocherlakota, president of the Minneapolis Fed from 2009 to 2015. “The takeaway from that, I guess, is monetary policy can’t really do much at this stage.”

Investors have instead been laser-focused on the White House and Congress -– and whether they’d manage to deliver fiscal support for businesses and workers, as Americans hunker down at home to avoid infection. In Europe too, fiscal authorities were getting a rude wake-up call that spurred them into action.

“Monetary policy will be increasingly dominated by fiscal considerations – a trend that has been underway for time already,” Joachim Fels, global chief economic adviser at bond fund Pimco, wrote in a note after Sunday’s cut. That’s “exactly what is needed at a time of crisis when the conventional tools of monetary policy are largely exhausted.”

Nothing like this was in the forecast when the Fed began its review 16 months ago. At that point, it had just spent three years ratcheting its benchmark rate back up toward historically normal levels. But it didn’t make it very far.

On Sunday, as it returned to what’s known as the zero lower bound, the Fed said it will keep rates there “until it is confident that the economy has weathered recent events.”

Other developed-world central banks have been stuck in the zero-trap for decades, and struggled to get traction. That’s one reason why proposals more radical than anything on the Fed’s own radar have been bandied about with growing urgency by monetary policy wonks.

Negative rates, already attempted in Europe and Japan, have their advocates -- including President Donald Trump -- though Fed officials dislike the idea and Powell again dismissed it at his press conference on Sunday.

Former Vice Chair Stanley Fischer is among the supporters of monetary-fiscal cooperation: he co-authored a plan for the Fed to bankroll government spending, under specific conditions and with clear limits.

Others say the Fed needs a license to buy a wider range of securities than the government-backed ones it acquired in past rounds of QE. On March 6, Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren voiced support for the idea, while noting that an act of Congress would be needed.

The Fed’s review was focused on a different kind of question -- mostly, why the 2% inflation target had been repeatedly missed on the downside since 2008. The expected takeaway was an approach labeled average-inflation targeting. Policy makers would keep interest rates low enough, and run the economy hot enough, to meet the goal on average over a longer period.

Big Lift

In the coronavirus world, the economy is set to cool rapidly regardless of where interest rates are, as spending on things like travel and dining plummet overnight, and workers get laid off.

Unemployment is at 50-year lows now. But policy makers recall how it almost doubled in a span of 18 months during the financial crisis – peaking at 10%, and not dropping back to 5% for another six years.

Meanwhile, yields on even 30-year government bonds far below the 2% inflation target, investors -- signaling that the Fed won’t have to worry about the timing of a rate-hiking cycle, the kind of strategic question the review was designed to answer, for a long time to come. Instead, firefighting tactics are again the order of the day.

Looking back on the period since 2008, Nathan Sheets -- a former Fed and Treasury official who’s now chief economist at PGIM Fixed Income in Newark, New Jersey -- says the attempt to raise rates now looks like a “temporary phenomenon.”

“The European Central Bank has been stuck at zero. The Bank of Japan has been stuck at zero for even longer,” he said. And markets think “it’s going to be really hard for the Fed to launch again.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Matthew Boesler in New York at mboesler1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Margaret Collins at mcollins45@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.