The Fed Typically Kills Expansions. Now It Must Save This Record Upswing

The Fed Typically Kills Expansions. Now It Must Save This Record Upswing

(Bloomberg) --

The frequent killer of past U.S. economic expansions is being counted on to extend the life of the now record-long current one.

The hoped-for safeguard is the Federal Reserve — which even former Chair Janet Yellen admits has a history of snuffing out upswings by raising interest rates to contain inflation.

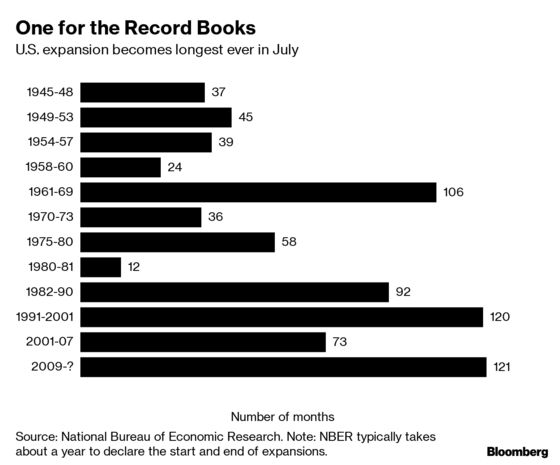

But now, with inflation too low for the Fed’s taste, Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues know they’re on the spot to prolong the expansion, which on Monday becomes the longest in records back to 1854 — at 10 years and one month.

Economists generally believe the Fed will succeed in preventing a recession, despite some downside risks.

“My colleagues and I have one overarching goal,” Powell told reporters on June 19. “Sustain the economic expansion, with a strong job market and stable prices, for the benefit of the American people.”

That would also incidentally benefit President Donald Trump, who’s up for re-election next year and has repeatedly urged the central bank to ease policy to boost growth.

The Federal Open Market Committee is expected to lower interest rates at its July 30-31 meeting, perhaps by as much as a half percentage point, as it battles heightened trade tensions and slowing global growth.

And it may not stop there. Jason Cummins, chief U.S. economist at hedge fund Brevan Howard Asset Management, said at a June conference that the Fed could end up reducing rates by 1.25 percentage points to bolster the economy and boost inflation.

The expansion is entering record territory under some threat.

“There are some dark clouds on the horizon,” said Robert Dye, chief economist at Comerica Inc. in Dallas.

Economists surveyed by Bloomberg in June saw a 30% chance of a recession in the next year, according to the median estimate. That compares with 15% in late 2018.

Growth was already on course to slow this year as the stimulative effects of last year’s tax cuts waned.

Then the U.S. was hit by what Cummins dubbed a “deglobalization shock” as Trump’s trade battles with China and other nations sapped business confidence and hurt the world economy.

Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping decided on Saturday to resume trade negotiations after a six-week stalemate, with the U.S. agreeing to a temporary freeze on further tariffs on Chinese goods. Stocks advanced globally Monday after the truce and U.S. equities rallied to record highs.

Still, the impact of existing tariffs imposed from the trade war is trickling through the economy. A gauge of U.S. factory activity fell in June for the third straight month to its weakest level since October 2016, according to a survey of purchasing managers by the Institute for Supply Management released Monday. The measure of new orders fell to 50, the lowest since December 2015 and equaling the dividing line between growth and contraction.

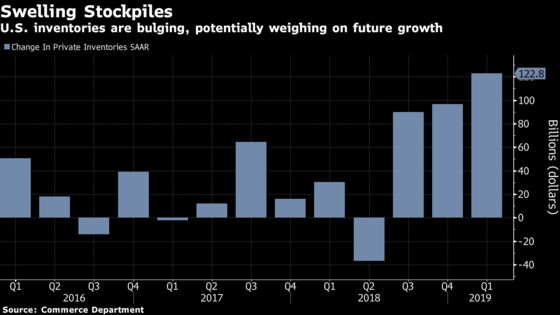

The hit to manufacturing from the trade tensions has led to a pile-up of unwanted inventories that companies will need to work off, curbing production and growth in the process.

And it’s resulted in an economy that’s overly reliant on one engine to sustain the expansion — consumers — as businesses have curbed investment and residential construction has lagged.

“The economy has become less well balanced and a little more fragile,” said Andrew Hollenhorst, chief U.S. economist for Citigroup Inc.

That puts a premium on a continued strong job market to provide the fuel for consumer purchases.

After a surprise slowdown in payrolls growth to 75,000 in May, net hiring probably picked up to 160,000 in June, according to the median forecast of economists surveyed by Bloomberg. The data are due July 5.

In the face of the trade-driven headwinds, some economists question how potent the expected Fed rate reductions will be, arguing that lower borrowing costs won’t induce businesses spooked by tariffs into stepping up their spending.

“The biggest drag on investment is uncertainty stemming from the U.S.’s erratic trade policy — something the Fed is powerless to address,” Megan Greene, incoming senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, said in an e-mail.

San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly pushed back against that line of reasoning in a Bloomberg Television interview last week.

“Businesses do respond to the sense that the economy is going to be on a sustainable pace or it’s going to falter,” she said. “That mood shift can be very much supported by the actions of monetary policy.”

A big advantage of the widely expected rate reductions may actually be defensive. Without them, financial markets could crater, dragging down economic growth.

“The main benefits of the Fed cutting right now is to prevent another stock market correction like we had in the fourth quarter,” said Ethan Harris, head of global economics research at Bank of America Corp.

In a sense, it’s a perverse version of the so-called Greenspan put — the belief among investors that former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan would ride to the rescue whenever markets dropped precipitously. In this case, investors are betting on Powell to prevent a plunge from even happening.

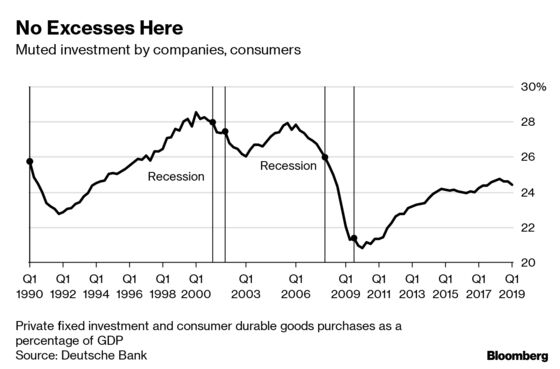

The expansion does have some things going for it. Partly because it’s been so lackluster, it has not built up some of the excesses that typically precede downturns — a bubble in house prices and home construction in 2007 and a run-up in stock prices and business investment in 2001. And inflation has remained muted.

It was in 1997 that the late Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Rudiger Dornbusch fingered the Fed as the culprit for killing off growth.

“None of the U.S. expansions of the past 40 years died in bed of old age,” he quipped. “Every one was murdered by the Federal Reserve.”

But that was from a time when policy makers were prone to worrying about inflation being too high, not too low. At 1.5% in May, it’s well shy of the Fed’s 2% target and on its own could be a reason for a rate cut.

With the support of the Fed, “this expansion can go on for a good while longer,” said Peter Hooper, global head of economic research for Deutsche Bank.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Scott Lanman at slanman@bloomberg.net, Margaret Collins "Peggy"

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.