The Fed Is Fighting for Control of Its Key Interest Rate

Powell said the rising fed effective rate is “a problem we can address with our tools, and we’ll use them if we have to.“

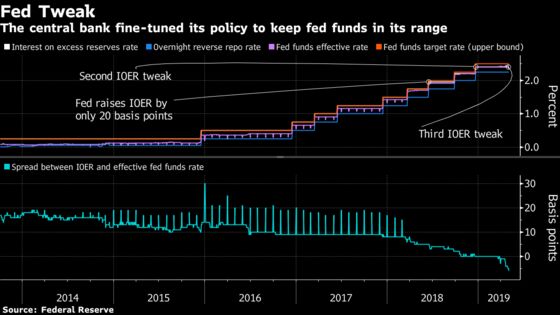

(Bloomberg) -- If a ship crossing a wide and placid harbor yaws so far that it almost hits the channel markers, its captain might want to have the rudder adjusted. That’s essentially what the Federal Reserve has done three times since 2018. With the fed funds rate inching disconcertingly close to the top of the central bank’s target range, it chose to make unprecedented changes in June, December and May to one of its associated policy-setting tools: the interest on excess reserves rate. Now, following the latest tweak to IOER, as it’s known, market observers will be watching to see if the gap between fed funds and the upper bound of the central bank’s target range narrows again. That potentially sets the stage for further adjustments, although there are also questions: How much more can they keep tinkering? Do policy makers need another tool?

1. Why has the Fed been adjusting IOER?

In December 2015, the Fed responded to improving economic conditions by raising interest rates that it had cut to near zero during the financial crisis. Since then, it’s increased the range another eight times, to 2.25 percent to 2.50 percent currently. For most of that time, the effective fed funds rate -- the average of what borrowers in the market actually paid -- rested comfortably near the range’s midpoint, just like it’s supposed to. But since the beginning of 2018, fed funds has been creeping higher. It was just five basis points below the top end of the range before the IOER adjustment in May 2019. Right after, the gap widened to nine basis points.

2. What is the fed funds rate?

It’s the rate at which big banks make overnight loans to each other from the reserves they keep on deposit at the Fed. Because it’s the basis for everything from credit card and auto loan rates to certificate of deposit yields, Fed officials use a range of policy tools to exert control over it and thereby influence the direction of the broader economy.

3. How does that work?

Differently than it traditionally did. Before 2008, the Fed used a playbook based on the fact that reserves were in short supply. If policy makers wanted the fed funds rate to fall, the New York Fed’s Open Markets desk would buy government securities from depository institutions. That increased their reserves, meaning they had more to loan out, which in turn meant lower rates. If it wanted the rate to rise, the desk would sell securities, draining reserves and prompting banks to charge more to lend out what they had left.

4. What about now?

In response to the financial crisis, along with cutting rates, the Fed bought trillions of dollars of bonds in a program known as quantitative easing. It paid for the bonds by creating vast new bank reserves. With all that money on hand, banks had far less need to borrow from each other overnight, meaning that the Fed’s old tools of adding to or reducing reserves had less impact, forcing monetary authorities to come up with another way to influence the effective rate. Enter the IOER rate.

5. What’s the IOER?

Starting in 2008, Congress allowed the Fed to pay banks for the surplus cash they store at the central bank. As Fed officials prepared for “lift off,” they realized that IOER could be a useful tool for managing rates. In theory, if the fed funds rate were to climb above the IOER rate, firms would begin lending reserves at that higher rate. But that increase in the supply of loans would then push the fed funds rate back down to the IOER level. They created another mechanism, called the overnight reverse repurchase agreement facility, to act as an interest-rate floor.

6. Why has fed funds been rising toward the top of the band?

No one is certain, but there are many theories. Some observers point to America’s tax season. The U.S. Treasury’s cash balance surged in April to a level last seen in 2016 as tax receipts poured in. That tends to reduce the level of bank reserves. As part of the collection, money-market investors withdrew cash from government funds to pay tax bills, which reduced their footprint in the repurchase-agreement market. The drop-off in reserves and fund outflows has driven up funding rates and also appears to have spilled into the fed funds market because repo’s attractive yields can draw some lenders away from the unsecured market.

7. The Fed’s already adjusted IOER, right?

Yes. IOER was cut five basis points in June 2018 and another five basis points in December 2018. Both times, this was done in conjunction with an increase in the Fed’s main rate benchmark. But in May 2019, the fed funds rate target was kept at 2.25 percent to 2.50 percent even as IOER was reduced.

8. What exactly does an IOER cut do?

The Fed says the move is designed to promote trading in the fed funds market at rates “well within” the Federal Open Market Committee’s target range. In theory, the shift discourages banks from parking money at the central bank -- where they’re paid IOER -- and prompts them to instead seek better rates by lending in other short-term markets, particularly fed funds.

9. Will the Fed just keep cutting IOER?

Following the latest decision, Chairman Jerome Powell said he doesn’t think the Fed will need to cut IOER again -- though he also said that after the prior two reductions. It almost certainly can’t keep doing this. More cuts could start to have major implications for everything from banks’ ability to meet their liquidity coverage ratios, to the signaling role of markets, to the future of the central bank’s policy-setting mechanism. Additional moves from here would bring IOER below the midpoint of the Fed’s target range, toward the critical overnight reverse-repo rate that now guides its floor, putting America’s monetary-policy framework to the test.

10. Can the Fed do something else to control fed funds?

Powell said in May 2019 that policy makers will, at a future meeting, discuss adding something to the Fed’s toolbox: a new kind of program for repurchase agreements. Others have recommended creating a repo facility. Guggenheim Partners LLC’s Scott Minerd is among them, explaining that IOER is not up to the task of controlling the fed funds rate.

11. What kind of repo facility?

No one is really sure. Powell wasn’t specific. But the Fed had been dropping hints that it could do something to cap short-term interest rates. The New York Fed has asked primary dealers whether it should consider a new tool to keep money-market rates more under control, according to people familiar with the discussions. And the St. Louis Fed has published blog posts outlining how a standing repo facility could enable the Feb to “effectively and efficiently implement monetary policy with ‘minimally ample’ reserves.”

The Reference Shelf

To contact the reporter on this story: Alexandra Harris in New York at aharris48@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Nick Baker, Lisa Beyer

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.