Fed’s $3.8 Trillion Balance Sheet Is Unlikely to Shrink More

The Fed’s $3.8 Trillion Balance Sheet Is Unlikely to Shrink More

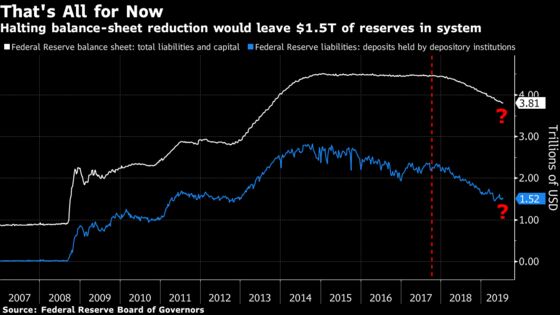

(Bloomberg) -- The Federal Reserve is widely expected to reduce interest rates this month. That probably means its campaign to shrink its balance sheet is over, leaving the central bank with trillions of dollars more than before the 2008 financial crisis.

Beginning a decade ago in a bid to fight the calamity, the Fed by 2015 accumulated as much as $4.5 trillion of debt, including Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. When policy makers began unwinding the portfolio at the end of 2017, primary dealers expected them to get it down to around $3 trillion or $3.5 trillion. But they’re not going to make it: Even after almost two years of cutbacks, the balance sheet is still brimming at $3.8 trillion.

Given the shift this year to a rate-cut stance, it might look unusual for the Fed to keep shedding assets. A rate cut tends to stimulate the economy; shrinking the balance sheet in theory does the opposite. President Donald Trump on Friday amped up pressure on the Fed along these lines, tweeting that it “must stop with the crazy quantitative tightening,” a phrase used in markets to refer to the balance-sheet reduction.

“By continuing balance-sheet rolloff and cutting interest rates, you can imagine someone yelling policy error,” said Jon Hill, a strategist at BMO Capital Markets. “Why run that risk?”

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s recent rhetoric about downside risks has cemented the case for the first rate cut in more than a decade. Fed funds futures are getting close to suggesting a half-point of easing at this month’s Fed meeting.

Beginning in October 2017, the central bank has been letting Treasuries and mortgage bonds on its balance sheet roll off, or mature rather than replacing them. The unwind gradually accelerated to a maximum $50 billion a month. Myriad Fed officials referred to the process as “watching paint dry.”

Then the markets swooned. A sell-off in global equity markets and drop in yields at the end of 2018 spurred investors such as DoubleLine Capital Chief Executive Officer Jeffrey Gundlach to blame the Fed and its balance-sheet unwind for unleashing volatility in the markets. In January, Powell said the unwind was likely to be completed sooner and with a larger balance sheet than previous estimates. Two months later, the Fed announced plans to slow the drawdown of their bond holdings and to end the reductions in September.

Even though an early end to the runoff seems like a foregone conclusion, Fed presidents have indicated they’ll be weighing the arguments. Richmond Fed President Thomas Barkin said in a Bloomberg TV interview on July 11 he thinks the central bank’s action on the balance sheet “hasn’t had a meaningful impact on the economy, the original ‘paint-dry’ scenario that was talked about two or three years ago.”

And there are arguments to be made for letting the unwind run its course for another two months. In a Bloomberg opinion piece published July 1, William Dudley, former head of the New York Fed, said if the runoff ended early it would make the balance sheet seem more important than it is, as well as contradict the central bank’s earlier statements that short-term interest rates would be the “primary tool of monetary policy.”

An early end may also rattle the market for Treasuries maturing in one year or less. That’s because the Fed would return to buying Treasuries in the secondary market -- including bills -- as the government is already in the middle of slashing short-end supply to preserve its borrowing authority under the debt ceiling.

NatWest Markets strategist Blake Gwinn said an early end could also affect the Fed officials’ plans should they need to deploy their balance-sheet again. “To do this takes away credibility of future balance sheet actions,” he said. “It’s a bad idea,” he added. “And for what? To avoid pretend confusion?”

To contact the reporters on this story: Alexandra Harris in New York at aharris48@bloomberg.net;Matthew Boesler in New York at mboesler1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Nick Baker, Mark Tannenbaum

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.