The Fed Is Entrenched in the Repo Market. How Does It Get Out?

Next year will test whether the Fed can end its interventions without chaos re-emerging.

(Bloomberg) -- At the Federal Reserve, 2020 will be all about making the repo market boring again. Policy makers will find this easier said than done.

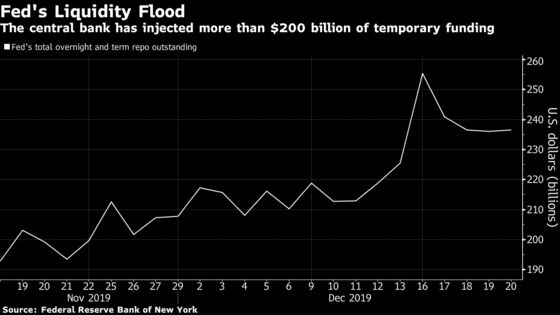

The central bank’s liquidity injections -- including almost half a trillion dollars earmarked to ensure New Year’s Eve is a snooze -- and Treasury bill purchases have nudged the vital market for repurchase agreements back toward normalcy after a funding crunch sent rates soaring in September. This has anchored the Fed’s benchmark rate firmly within policy makers’ preferred range of 1.50% to 1.75% and caused T-bill yields to fall.

But next year will test whether the Fed can end its interventions without chaos re-emerging. Chairman Jerome Powell recently said the Fed isn’t trying to eliminate all volatility from markets. However, if the repo market is erratic, it signals the Fed doesn’t have good control over the financial system’s plumbing. That’s something policy makers and the broader market can’t tolerate.

“It is all about credibility,” said Peter Yi, senior vice president of short duration fixed income at Northern Trust Asset Management in Chicago. “Even if you announce some fancy new trains, you also have to make sure they run on time. The Fed is going to have an important role in how 2020 plays out.”

Since the rate on overnight repo spiked to 10% on Sept. 17 from around 2%, the central bank has been conducting overnight and term repo operations to help rebuild banking reserves, adding $237 billion of liquidity. It’s also prepared to inject up to $490 billion around Dec. 31.

This year proved the repo market isn’t working without the Fed’s help, and the next issue is how to wean the market off of these liquidity injections without causing a disruption, according to Lale Topcuoglu, senior fund manager and head of credit at J O Hambro Capital Management Ltd.

“We may have December in control,” Topcuoglu said on Bloomberg Television. “The question is, there’s January. There’s February. There’s March quarter-end. There’s April.”

The last month on her list could be especially tricky. The U.S. tends to issue fewer Treasury bills in April because Americans’ income-tax payments leave the government flush with cash. This could eventually create “intense competition” for T-bills, especially with government-fund assets at record levels, said Jefferies money-market economist Thomas Simons. That could drive bill rates even lower.

Money-market fund managers are already having to adjust their allocations. Rob Sabatino, global head of liquidity at UBS Asset Management, said the Fed’s intervention has caused funds to put less into repo and move out of T-bills and into coupons in order to boost their returns by a few basis points.

If downward pressure continues on short-term rates, Sabatino said money funds may opt to return to the central bank’s infrequently used overnight reverse repo facility. Usage of that program has dwindled to $5 billion a day in 2019, down from $11.9 billion in 2018.

The Fed says it plans to buy $60 billion a month of T-bills to keep boosting reserves until sometime in the second quarter. But the timing is fluid given that policy makers haven’t figured out exactly how much the appropriate level of reserves is. Officials have said it’s probably at least where reserves were in September, which was about $1.3 trillion. Strategists at TD Securities and Bank of America suspect it’ll end up around $1.6 trillion to $1.7 trillion.

“The Fed has not given the market really any good guidance about what the end game is, and frankly it’s high time,” said Mark Cabana, head of U.S. interest rate strategy at Bank of America. He wants more concrete guidance on the level of reserves the central bank is targeting and on the prospects for regulatory changes.

JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon said in October that the bank was unable to deploy cash to calm the market because of liquidity regulations put in after the 2008 financial crisis. Powell said he’s open to ideas for modifying supervisory practices that don’t undermine the safety and soundness of the financial system.

Many market participants want a sense from the Fed on whether it will create a standing repo facility, a tool that would let eligible banks convert Treasuries into reserves on demand at an administered rate. Powell said Dec. 11 that it will take some time to evaluate and create parameters for that.

Northern Trust’s Yi said the Fed will eventually have to establish a more permanent facility with expanded counterparties, as well as continue bill purchases to boost excess reserves. Given Powell’s comments, UBS’s Sabatino is skeptical the central bank will ever introduce such a tool, even though many are clamoring for it.

“I wouldn’t hold my breath on a standing repo facility in the first half of next year or any time at all,” he said.

This lack of clarity on the Fed’s long-term objectives increases the likelihood the central bank becomes more entrenched in the daily fabric of the funding markets. That will make it harder for the space to function on its own and even more difficult for policy makers to untangle themselves.

“Every single day we’re getting our funding from the Fed, that starts to get ingrained in the business,” said NatWest Markets strategist Blake Gwinn. “The longer they go on as the major source of liquidity, the harder it’s going to be to extricate themselves.”

--With assistance from Emily Barrett.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alexandra Harris in New York at aharris48@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Nick Baker, Greg Chang

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.