A Climate Summit in the Heart of Coal Country

he UN’s COP24 conference will seek to create new rules for cutting carbon emissions.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As government officials, scientists, and green activists gather for the United Nations climate conference in Poland, Adam Pietron has a few words of advice: Try to avoid the air. Pietron lives in Katowice, a coal-mining and steel-making stronghold for centuries that's host to the conclave, and he says the pollution is so bad that this year he installed an air purifier.

“Sometimes the smog is terrible,” Pietron says, consulting an app on his phone that measures air quality. “A few days back, it was tough to breathe.”

More than 22,000 delegates from nearly 200 countries are coming to a city as closely tied to the carbon economy as almost anywhere on earth. Katowice is the capital of Silesia, the heart of the coal industry in the country with Europe's worst air--mostly due to its continued reliance on the fuel for everything from massive power plants to basement furnaces.

The meeting, known as COP24 in UN jargon, is being sponsored by two power-generating companies and Europe's biggest producer of coking coal. The venue for the Dec. 2-14 conference sits on the site of an old coal mine, and its design was inspired by mining culture: The predominant color inside and out is anthracite, and the hallways and meeting rooms have irregular angles meant to resemble mineshafts. And just a 15-minute drive to the south is the Wujek mine, the site of violent strikes during the Solidarity protests against communism, which has been churning out coal since 1899.

“It's like hosting a culinary conference at a venue that serves frozen pizza,” says Lauri Myllyvirta, a Greenpeace air pollution analyst.

Delegates to the meeting, an annual event that moves from country to country, will seek to transform pledges made in Paris three years ago into an international rulebook aimed at curbing greenhouse gas emissions. While the Paris Agreement has focused attention on the scale of the cuts needed to rein in fossil fuel pollution, there's growing resistance to the hard choices that will be required.

The Trump administration has made no secret of its skepticism regarding climate change. Australia has adopted that viewpoint, and Brazil is leaning toward it since the October election of Jair Bolsonaro as president, who has promised to prioritize jobs and mining over protecting the environment. And Brazil, India, China, and other developing countries bristle at being asked to make deep cuts to their coal consumption. Two centuries after the Industrial Revolution, they argue, the West is responsible for the problem and should bear the brunt of the costs for cleaning it up.

And then there's the host country. Fearing mining unions and lacking a clear alternative, successive Polish governments have been slow to shift away from carbon. Even as most of Europe will be coal-free by 2025, Poland says it expects the fuel to account for more than half its energy in 2030, and more than a third in 2040. While those targets, announced on Nov. 23, represent an increasingly ambitious plan for Poland, they still fall far short of what's needed to rein in greenhouse gas emissions.

As host of the talks, Poland will play a crucial role in setting the tone of the final proclamation. The UN-sponsored event began after a 1992 treaty acknowledged the problem of global warming, and poor countries have long worked together to demand compromises from rich ones. With consensus required for any agreement, Poland's delegation--presiding over the meeting--will have a powerful voice in shaping it.

“Strong hosts can support parties to ensure that the whole is more than the sum of the parts, and negotiations spur faster action,” says Rachel Kyte, a top UN envoy on energy policy. “Weak hosts can see bad actors slow things down.”

Lou Leonard, a World Wildlife Fund official overseeing climate change and energy policies, says Poland will face great pressure from its EU partners to move forward on what was agreed in Paris. While the government hasn’t fully embraced the goals of the green-leaning delegates, growing concern among private companies will give the Warsaw leadership “political cover” to promote deeper cuts in carbon emissions, Leonard says. “Poland would be an unlikely hero in this chapter of the Paris story, but they are set up to succeed if they want to seize their moment,” he says.

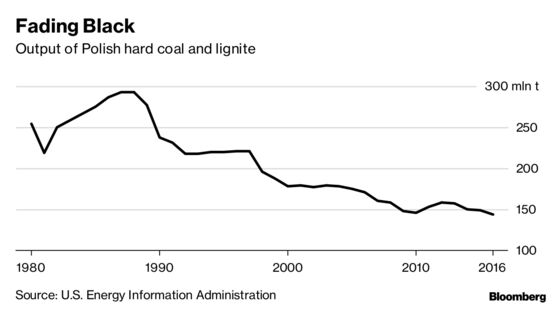

Though Poland's coal production fell to 144 million tons in 2016 from a peak of 293 million tons in 1988, the country sits on Europe's biggest reserves of the fuel. And it still accounts for 80 percent of the country's electricity—the primary reason Poland is home to 36 of the EU's 50 most-polluted cities. Katowice, with a population of 300,000, is on that list, and delegates to the conference will understand why if there's a cold snap during the conference. When the temperature drops, coal is piled into furnaces and cities start sending alerts advising residents to stay inside.

“People still need to heat their houses in December,” says Environment Minister Henryk Kowalczyk. “The air quality will show the reality of our situation.”

Still, Katowice may point the way forward for Poland. It's building bike lanes and installing plug-in stations for electric cars, and it plans to spend 565 million zloty ($150 million) by 2030 on smog-fighting measures such as replacing coal-fired home furnaces. That fits with a nationwide push to wean Poland from coal more quickly, though the latest plan envisions a greater reliance on nuclear power than on sources such as solar and wind.

Those are the kinds of choices conference delegates will face on a global scale. The final agreement will require countries to find common ground on a tangled web of issues ranging from payments to poor nations, the scale and direction of mitigation efforts, and how to report emissions. It won't be easy, says Rachel Kennerley, a climate campaigner at Friends of the Earth, but the delegates have a chance to set the pace for global climate policy for a generation.

“There’s an absolute mountain to climb, and lots of different countries have very different ideas,” Kennerley says. “We’re not pessimistic, but it’s a huge challenge to deliver a rulebook that will actually limit temperature rise.”

--With assistance from Marek Strzelecki.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net, Reed Landberg

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.