Templeton India's Contrarian View Makes It Best Bond Manager

When it comes to investing, Santosh Kamath doesn’t tend to run with the herd.

(Bloomberg) -- When it comes to investing, Santosh Kamath doesn’t tend to run with the herd.

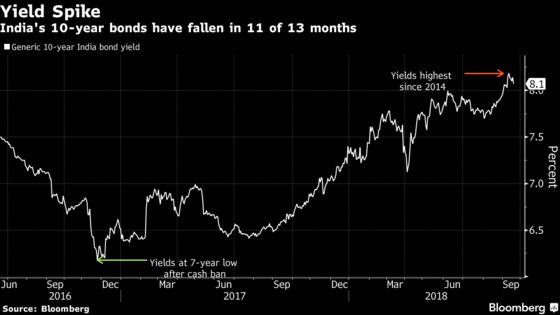

In late 2016, when most Indian fund managers thought benchmark yields would stay subdued after falling to a seven-year low following the government’s ban on high-value currency, Kamath, the head of fixed-income funds at Franklin Templeton Asset Management (India) Pvt., switched from longer-tenor papers to shorter ones.

The strategy has since proved rewarding, helping his funds beat peers despite the local bond market being roiled by the worst rout in two decades.

“This one trade paid off very handsomely,” Kamath, who oversees the equivalent of about $8.5 billion, said in an interview in Mumbai. “Anywhere there is a majority trade, we get a bit fearful. Most of our competitors underperformed because they carried longer maturity.”

Fear is widespread now. Bonds have fallen in six out of eight months this year, sending 10-year yields to the highest since 2014, and the rupee has hit a series of new lows amid a rout in emerging markets. But Kamath is staying long on shorter-maturity corporate bonds as the losses in sovereign debt could deepen with the worsening of India’s economic metrics.

“If you are at the shorter-end of the curve and invest in high-yield corporate bonds, you lose less as mark-to-market impact is low and you get to redeploy funds at a higher rate when interest rates move up,” he said. “And all rates -- lending, deposit and G-Secs -- are inching up due to imbalances in macro fundamentals.”

Sovereign bonds declined, with the benchmark 10-year yield rising two basis points to 8.10 percent at 10:34 a.m. in Mumbai, while the rupee slid 0.3 percent to 72.4325 per dollar.

The carnage in government bonds isn’t going to end soon, Kamath said, as high oil prices -- India’s top import -- threaten to boost inflation and pressure companies borrowing costs, worsening a negative spiral for the world’s fastest-growing big economy. Overseas funds have pulled $1.1 billion from local bonds this month, adding to the weakness in the rupee, Asia’s worst performer this year.

“A combination of deteriorating macros but improving growth is negative for the currency and interest rates,” Kamath said. “I won’t be surprised if there is an out-of-turn liquidity tightening measure, predominantly guided by concerns about the rupee.”

The central bank raised rates twice this year and is due to review policy in the first week of October.

It’s against this backdrop that the $1.6 billion Franklin India Short Term Income Fund has risen 7.6 percent over the past year, the top performer among short-duration funds, according to New Delhi-based Value Research India. The Credit Risk Fund has returned 6.7 percent and the Dynamic Accrual Fund 6.6 percent, topping their categories, the data show.

Some other views Kamath expressed during the interview:

- The 10-year yield will rise another 25-50 basis points over the next six-to-12 months

- India may have a balance-of-payments deficit which will force the RBI to supply dollars to the market, sucking out rupee liquidity, and that will lead rates higher

To contact the reporter on this story: Kartik Goyal in Mumbai at kgoyal@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Tan Hwee Ann at hatan@bloomberg.net, Ravil Shirodkar, Mark Cudmore

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.