Surge in U.S. Health-Insurance Prices Exposes Quirks in Data

The latest CPI data showed health-insurance prices rose 1.9% in August from the prior month and 18.6% from a year earlier.

(Bloomberg) --

The record surge in U.S. health-insurance costs seen in the Labor Department’s consumer price index Thursday highlights a key quirk in that line item: It’s not directly based on prices paid by consumers.

Instead, it’s an indirect measure based on retained earnings, or what insurers have after paying out claims. And unlike other prices in the CPI that are obtained each month, the department takes data collected annually and spreads the change equally over 12 months.

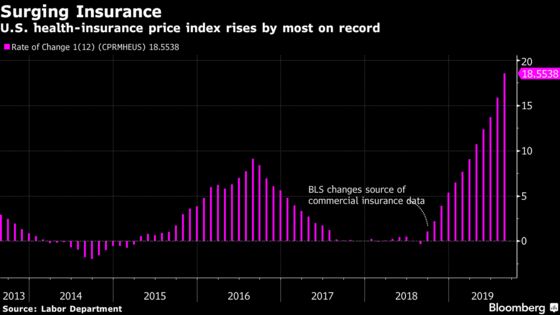

The latest CPI data showed health-insurance prices rose 1.9% in August from the prior month and 18.6% from a year earlier, both records in figures going back to 2005.

That’s far different from the trend in the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation gauge, the Commerce Department’s personal consumption expenditures index. The health-insurance component of that measure has slowed in recent months and was up 1.4% annually in July. To make things more complicated, the PCE measure relies on data from the Labor Department’s producer price index covering health-insurance premiums paid by different sources, not just out-of-pocket expenses.

Even though health insurance accounts for just 1.2% of the overall CPI, the measurement difference makes up a significant part of the current gap between the CPI and PCE inflation. The CPI rose 1.7% in August from a year earlier, while the PCE’s annual gain was 1.4% in July. That suggests Fed officials are likely to look through the health-insurance impact on CPI as they debate additional interest-rate cuts.

On the CPI, the Bureau of Labor Statistics tries to conceptually measure what Americans pay into insurance plans compared with what they receive in terms of benefits.

An increase in the index suggests the retained earnings of insurers are rising, not necessarily that Americans are paying more for health insurance. However, it could reflect both.

Insurance companies have been collecting more money from people, but “what they’re paying out for services has actually been falling,” said Laura Rosner, partner at MacroPolicy Perspectives LLC in New York. More broadly, “there has been quite a significant moderation in health-care inflation and that seems to be driven by efforts to lower costs and improve efficiencies,” she said.

Also, around when the CPI health-insurance measure began picking up in September 2018, the BLS switched data providers for commercial insurance information on total premiums and benefits. It’s unclear if -- or by how much -- this factors into the sharp increase in the index.

Democrats’ Plans

Even with questions around the data, the latest CPI figures may add to concerns about rising costs of health care and could provide ready talking points for Democrats who are advocating wider access to care as they battle President Donald Trump and Republicans in 2020.

Premiums have been rising for years for the majority of Americans under 65 who get health insurance through employers, roughly 156 million people. The cost of those premiums is split between employer contributions and the premiums that workers pay.

For a family plan in 2018, the total premium reached almost $20,000, with workers contributing more than $5,500 of that sum, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit health research group. Average total premiums for family coverage increased 45% between 2009 and 2018, according to Kaiser’s data -- more than double overall CPI inflation.

Rising premiums tell only one part of the story. Americans increasingly face higher deductibles and other forms of cost-sharing, so even people with insurance are more exposed to the financial consequences of illness or injury.

Among employer plans with a deductible, the average deductible for single coverage in 2009 was $826, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation data. That figure -- the amount one has to pay before insurance coverage begins to cover medical costs -- almost doubled by 2018, to $1,573.

To contact the reporters on this story: Reade Pickert in Washington at epickert@bloomberg.net;John Tozzi in New York at jtozzi2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Scott Lanman at slanman@bloomberg.net, ;Drew Armstrong at darmstrong17@bloomberg.net, Mark Schoifet

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.