Startups Lose in a Low-Rate World, and the Fed Is Blaming Itself

America’s startup rate has been falling sharply and business has become more concentrated since the 1990s.

(Bloomberg) -- As startups become increasingly rare and industries grow more concentrated, the U.S. central bank is pointing a finger -- at itself.

Low interest rates may be driving big companies to buy up ideas, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia argue in a new paper. Bigger firms are more leveraged, the authors find, which is probably because they operate in more business lines and enjoy relatively stable levels of employment and sales. Diversification boosts creditworthiness, leaving large firms better placed to borrow against future cash flow when they get hold of new ideas.

That financing advantage gives incumbents a big incentive to buy innovative competitors in a low-rate environment, which eliminates startups and leaves the subsuming company with greater market share.

(You’re reading Bloomberg’s weekly economic research roundup.)

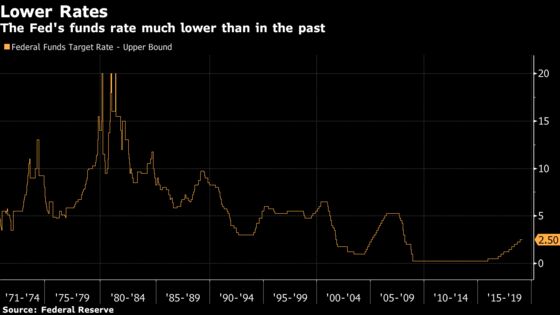

That logic also happens to fit with recent U.S. data. America’s startup rate has been falling sharply and business has become more concentrated since the 1990s, and “the driving force is the decline in the risk-free interest rate over the same period,” Satyajit Chatterjee and Burcu Eyigungor write.

The Fed guides interest rates, though today’s low-rate reality isn’t necessarily the central bank’s fault. Officials are keeping borrowing costs low partly because the interest rate that neither stokes nor slows growth has fallen across advanced economies. That’s happened as populations age, consumers save more and demand for safe interest bearing investments abounds. Those trends look unlikely to reverse anytime soon.

Usually, theory would suggest that a low-rate environment should be good for firms overall -- making it cheaper for them to borrow and grow -- but that doesn’t account for market structure and competition, according to a recent and related working paper by Princeton University’s Ernest Liu and Atif Mian as well as the University of Chicago Booth School of Business’ Amir Sufi. The paper argues that industry leaders are likely to respond more aggressively to low borrowing costs than industry followers. By doing so, they are able to boost their productivity and expand their market footprint.

“The gap between the leader and follower increases as interest rates decline, making an industry less competitive and more concentrated,” the authors write. And once a company wins, it can dramatically slow its investment in productivity enhancing technologies and expansion.

“When interest rates are already low, this negative effect of lower interest rates on industry competition tends to lower growth and overwhelms the traditional positive effect of lower interest rates on growth,” the authors write.

Also worth a read this week...

Mario Draghi’s July 2012 promise to do “whatever it takes” to right the euro area economy had big effects on bank lending behavior, the authors of a European Central Bank study find by studying -- surprisingly -- Mexico. They look at the Latin American country because it was relatively unaffected by the euro crisis, and European and other foreign banks had a major presence in the country. They find that European banks in Mexico had been pricing their loans more aggressively than other lenders. That may be because “when the franchise value is under pressure the bank aims to preserve its overall profitability by engaging more in risk-taking globally.” The European banks fell back in line with counterparts in Mexico after Draghi’s pledge.

When the Bank of England slashed rates following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, each 1 percentage point in monetary accommodation led to around a 3.5 percentage point increase in annual employment growth at businesses that relied on local customers from 2009 to 2010. That effect came as people with variable mortgage rates found more money in their pockets. “Although U.K. unemployment rose by around 3 percentage points in the year following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the extraordinary monetary stimulus carried out by the MPC surely protected the aggregate economy from a fate far worse,” Fergus Cumming writes.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeanna Smialek in New York at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Randall Woods, Robert Jameson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.