(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Here’s some good news for America’s flood-hit farmers: China is looking at shifting agricultural tariffs, imposed as part of its tit-for-tat trade war with President Donald Trump, to other products instead.

Levies of some sort would still remain in place, people familiar with the situation told Bloomberg News, but move to non-agricultural items. That would allow Beijing to match Washington’s tariffs, which the U.S. government intends to maintain for leverage to open up China’s economy.

The problem with squeezing this balloon is that there aren’t all that many other places for the tariffs to go.

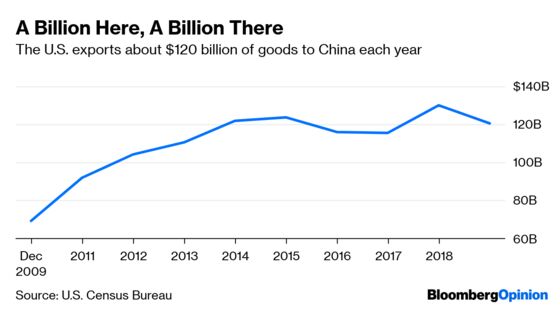

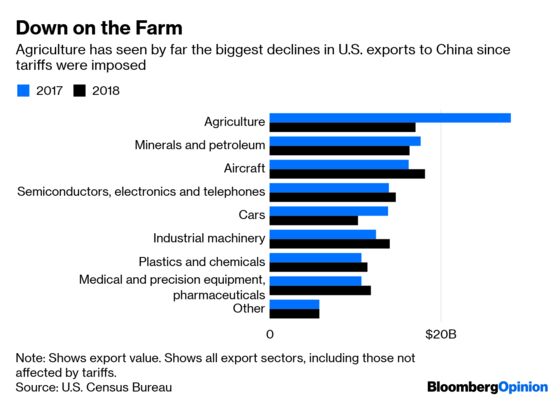

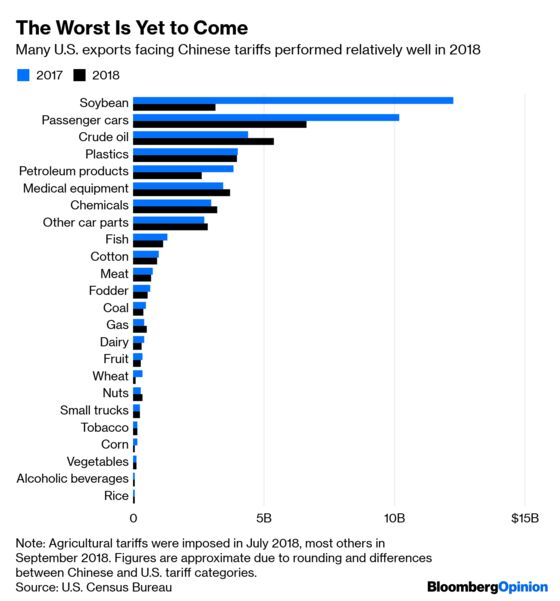

China typically imports about $120 billion of goods from the U.S. each year, of which a nominal $50 billion are currently subject to retaliatory tariffs. Under the lists issued by China’s Ministry of Commerce, roughly a third of the total was imposed on agricultural goods such as soybeans, animal feed, grains and tobacco, worth around $17 billion before tariffs were imposed in 2017. Another third went to cars, while the balance was split between energy products, medical equipment and chemicals.

The automotive component of that – worth some $13 billion of the total in 2017 – was already suspended at the start of this year, and is likely to continue in abeyance until the current talks are resolved. So how do you replace all those tariffs lost from agriculture?

The biggest pot of money out there is in petroleum and minerals, which accounted for about $18 billion in imports before tariffs were imposed. But that’s an unlikely candidate: For one thing, increased volumes of crude oil and natural gas are one of the best ways for China to close its trade deficit with the U.S., a key priority for Trump. For another, as with farming, the mining and processing of petroleum, coal and metals happens disproportionately in stretches of the country like the Midwest, Great Plains and Texas which voted Republican in 2016.

Next there’s aircraft, worth about $16 billion. In theory, there’s potential here: While some of these exports are included on China’s current tariff list, those weighing more than 45 metric tons are exempt – a qualification that excludes all of Boeing Co.’s big sellers. At the same time, given the problems of the 737 Max 8, accepting tariffs in this area would be both politically controversial in Washington, and economically meaningless for a China that may not be importing many Max 8s for awhile, anyway.

The likeliest place where tariffs would land is in the manufacturing sector. Semiconductors, telephones, computers and related equipment represent $14 billion or so of U.S. exports to China. Industrial machinery accounts for about $13 billion, and a decent slice of the $11 billion plastics and chemicals industry is exempt from the current levies. On top of that, a range of precision equipment and pharmaceuticals are currently in the clear, worth another $7 billion or so.

It’s hard to believe that China would be too upset if the costs of U.S. imports in these sectors went up. The Made in China 2025 industrial plan – a casus belli for the current trade war itself – sets ambitious targets for increasing local sourcing of many of these products, from drugs and farm equipment to advanced machinery, telephony and sophisticated materials. Putting up tariff barriers to imported manufactures has been a favorite way of cultivating domestic industry since the days of William Jennings Bryan.

It’s possible that negotiators could find some less sensitive niches of industry that wouldn’t hit America’s manufacturers. Indeed, a tariff list that amounted to $50 billion in theory but not in practice would bear some resemblance to the current one, which actually affects more like $36 billion in goods once you account for the exclusion of car exports.

Still, given the twin imperatives of protecting Trump country and using commodity exports to close the trade deficit, it’s clear that any transfer (as opposed to suspension) of the farm tariffs would leave valuable parts of America’s economy in jeopardy. There simply aren’t enough large export sectors to avoid that outcome.

Washington’s trade negotiators should do their best to avert such a result. If it came about, China would have succeeded in raising barriers to the most sophisticated U.S. manufacturers, all while arguing it was doing the Trump administration’s bidding. Such a deal would push its own economy into the future, while driving America back into the past. China didn’t invent the famed judo technique of using your opponent’s strength against it – but it seems to be learning.

These figures are very approximate because they change each year, not least in response to the tariffs themselves.

Boeing and General Electric Co. should be concerned that aircraft and their engines are also a major target of the plan.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.