Smoke and Mirrors of EU Budget Math May Not Cut It After Virus

Smoke and Mirrors of EU Budget Math May Not Cut It After Virus

(Bloomberg) -- When the European Union presents its plan to rebuild its economy after the coronavirus, it’s likely to include three kinds of funding: taxpayers’ money, borrowed money and theoretical money.

Officials in Brussels have a tendency to pad out their flashy headline figures with the theoretical stuff. But investors trying to gauge the strength of the policy response would be advised to peer a little closer.

The last EU Commission’s flagship initiative aimed to spur 315 billion euros ($340 billion) of investment with 5 billion euros of public money from the European Investment Bank and a 16 billion-euro guarantee from the EU budget. The commission boasted that it beat that initial target by almost 50%. But its auditors weren’t convinced.

Now Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is trying to pull off the same trick with the virus recovery funds and that’s raising heckles among those who need to see real money.

On a videoconference with EU leaders last week, French President Emmanuel Macron railed against “fake” EU budget proposals, according to two officials familiar with the conversation.

The problem for von der Leyen and her team is that despite all the talk of European money, the EU’s budget is a paltry 1% of gross national income. And most of that is allocated to agricultural aid and subsidies to poorer members. The real fiscal muscle in Europe is still controlled by a handful of national governments -- and the Germans above all. So when the commission wants to make a financial impact, it is used to getting creative.

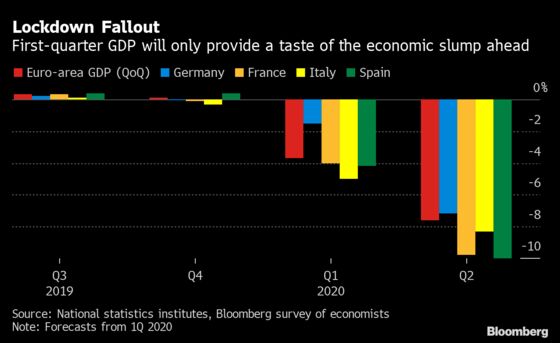

This time around though -- with the economy set to collapse by as much as 15% and public finances in some members stretched to the breaking point -- papering over the cracks may not be good enough.

“The commission should not fall again into the financial-wizardry trap just to avoid having to ask member states for the necessary additional funding,” said Lucas Guttenberg, deputy director of the Jacques Delors Centre in Berlin. “If member states are not willing to either put in substantially higher contributions or to let the EU borrow massive amounts in the markets, all the financial alchemy in the world will not suffice to ensure a full recovery.”

Von der Leyen says that the commission will be sticking to the same approach when it comes to measuring its recovery plan. “It’s known territory,” she told journalists this month.

Indeed, a draft commission plan leaked earlier this month contained a hefty dose of alchemy. It promised to “generate” 2 trillion euros of investments on the back of 320 billion euros of borrowing on financial markets. What’s more, it said that national contributions to the EU’s next seven-year budget will “remain modest” and will even be below the levels discussed before the pandemic.

It’s a familiar arithmetic for those who followed von der Leyen’s plans to generate trillions of euros to finance Europe’s energy transition or her predecessor Jean-Claude Juncker’s investment plan. The so-called Juncker Plan, started in 2014, offers a reference point.

Juncker’s idea was that by offering a small amount of funding or guarantees, the commission would be able to nudge private investors to back riskier projects that might otherwise have been starved of funding. By the end of 2019, the commission was reporting 458 billion euros of investment had gone to 1.1 million small- and medium-size businesses.

Auditor’s Doubts

The European Court of Auditors, however, took a more critical view. Its report last year concluded that many of the projects would have been funded anyway without the commission’s intervention and that in some cases, the commission’s estimates of how much additional investment it had triggered were overstated.

This time around there are added reasons for skepticism.

The Juncker Plan was set up right after the sovereign debt crisis and sought to encourage private investment. Attracting investors may be more difficult after the virus has crushed global demand, and some officials question whether there would be enough appetite to deliver on the commission’s projections.

The EU’s executive has been using a similar approach when calculating that some 3.4 trillion euros of funds has been deployed to tackle the crisis. That figure includes national fiscal measures already adopted and credit lines created to finance them, as well as liquidity guarantees which may not have to be drawn, reallocated funds from the EU budget and initiatives planned, but not yet rolled out.

“I fear that the commission’s favored concept of artificially inflating the supposed impact of its programs through guarantees and private financial injections will work in only a very limited way in the current situation,” said Markus Ferber, a lawmaker in the European Parliament for the German Conservatives. “Sooner or later we have to face the bitter truth, which is that we won’t have any choice but to put fresh money into the EU budget or, for example, the European Investment Bank.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.