Sliding U.S. Inflation May Provoke Fed Rate Cut Later This Year

Fed officials have already begun discussing the possibility in public ahead of their April 30-May 1 policy meeting.

(Bloomberg) -- U.S. inflation is sliding again, and this time Federal Reserve officials may feel compelled to respond.

After a gauge of price pressures central bankers watch closely finally rose above their 2 percent target last summer -- marking the first time north of it since 2012 -- it moderated to 1.8 percent in January, and some forecasters see it heading lower still throughout the first half of the year. That may be reflected in two Commerce Department reports slated to be published in the coming days.

Receding inflation could bolster the case for reducing interest rates in 2019, even though worries from earlier in the year about an economic downturn have largely passed.

Fed officials have already begun discussing the possibility in public ahead of their April 30-May 1 policy meeting. Meanwhile, investors are piling into bets that the benchmark federal funds rate will come down later in the year, even as they push U.S. stocks to record highs.

Chicago Fed President Charles Evans laid out the case on April 15, while speaking with reporters after a speech in New York.

“I think the answer has to be yes,” Evans said, when asked if low inflation could be grounds for a cut. “If core inflation were to move down to, let’s just say, 1.5 percent,” that would indicate the current level of rates “is actually restrictive in holding back inflation, and so that would naturally call for a lower funds rate, at least so that it was accommodative.”

His response highlights the way most policy makers think about how their interest-rate moves affect the economy. They believe people consider inflation when making decisions about borrowing and lending, so it’s important to focus on inflation-adjusted interest rates.

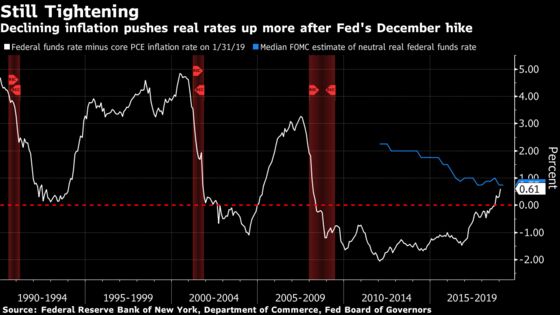

That means even if U.S. central bankers leave the fed funds rate unchanged -- which they have since raising it to just below 2.5 percent in December -- declining inflation effectively constitutes a tightening because it pushes up the so-called real rate, which in turn ought to slow the economy and possibly even put more downward pressure on inflation.

After their March meeting, Fed officials projected it would be appropriate to forgo additional rate hikes this year, which would help keep inflation at 2 percent. But some analysts think that inflation forecast is too optimistic, which means real rates may continue rising. In an April 17 report, JPMorgan analysts argued core inflation could fall to 1.5 percent as soon as next month.

If that prediction proves correct, the downward drift will come amid an official review of the current strategy for hitting the 2 percent target which was announced late last year.

Officials believe inflation expectations are a key determinant of actual inflation, and the centerpiece of the year-long review is a conference at the Chicago Fed in June, which will focus on how to convince the public that policy makers are serious about hitting their target.

Tepid inflation has also led Fed officials to ponder the other factor they believe determines price pressures in the economy: the job market. The theoretical relationship between unemployment and inflation -- known as the Phillips curve and prominent since the 1960s -- seems to have mostly disappeared in the data half a century later.

At a Feb. 22 conference in New York, San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly and her counterpart in New York, John Williams, suggested strong labor markets still drive inflation higher, but only in certain categories of goods and services such as housing.

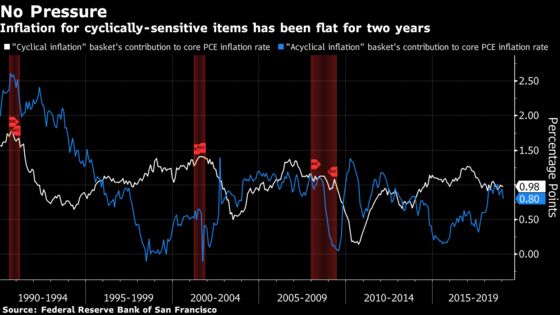

Daly cited two gauges developed by San Francisco Fed economists, which divide up the items in the inflation basket based on whether or not they are sensitive to cyclical pressures, and help explain why inflation rose last year before coming back down again.

The gauges show that the inflation rate for such cyclically sensitive items has been flat for the past two years, and remains well below levels achieved in previous expansions. The inflation rate for other items, which is harder for policy makers to influence, jumped last year before sliding again in January.

“To the extent we’ve got low inflation in an environment with sub-4 percent unemployment, I think that that’s indicative of the fact that we don’t have an active Phillips curve in this environment, and you have to look to other channels for signals about inflation,” St. Louis Fed President James Bullard told reporters on April 17 in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

“The other channel you need to look at is inflation expectations,” he said. “Those don’t look that good either, and so I am a little concerned about this.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Matthew Boesler in New York at mboesler1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.