RIP Phillips Curve? The Fed's Wonky Guidestar May Be Dimming

RIP Phillips Curve? The Fed's Wonky Guidestar May Be Dimming

(Bloomberg) -- The Federal Reserve may be losing its economic religion, or at least becoming more agnostic.

Central bankers believe -- often devotedly -- in a concept called the Phillips Curve. The idea is that very tight labor markets will force employers to raise wages, and they’ll charge consumers more to protect their profit margins. The end result? Low unemployment heralds higher inflation.

Prices have been too-low for most the of the past decade, but based on Phillips Curve-inspired logic, officials have been lifting rates to prevent inflation from accelerating suddenly. As of Wednesday, when the Federal Open Market Committee pivoted decisively toward keeping rates on hold, that rationale seems changed.

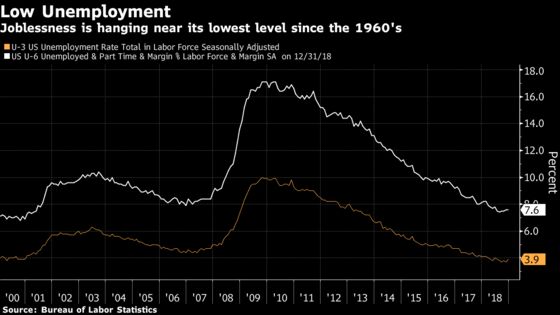

Unemployment remains historically low at 3.9 percent, and it’s well under the 4.4 percent Fed policy makers expect to prevail in the long run, yet the FOMC said this week it would be patient before next adjusting rates. Their base case is still that prices will move up -- but the fact that they’re now flying-by-sight instead of acting preemptively challenges their long-held orthodoxy that rates act with “long and variable lags” and they must move early to stay ahead of the curve.

“They’ve really just jettisoned the Phillips Curve,” said Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co. He said the Fed seemed less concerned about overshooting its 2 percent inflation target than before, even though price data haven’t budged much lately. “It doesn’t seem to be the data, it’s how they’re reacting to the data.”

Tight Markets

Officials have pointed to tight labor markets as a reason to continue raising rates out of caution for years. In recent months, that rationale has weakened as price gains continued to hover below 2 percent despite a long stretch of very-low joblessness.

Powell has said that while he believes in the Phillips Curve, prices have become less responsive to declines in unemployment. “It’s really more like a Phillips Line,” he joked in October. And this week, he signaled that the Fed actually wants to see higher inflation materializing before lifting again.

“I would want to see a need for further rate increases, and for me, a big part of that would be inflation,” he told reporters Wednesday. “It wouldn’t be the only thing, but it would certainly be important.”

Powell didn’t say how much of a price jump he needs to see. The Fed’s preferred gauge of core inflation is at 1.9 percent, and many economists expect it to hold steady through the first half of the year. The Fed itself forecast core inflation at 2 percent in 2019 in its December economic projections, down from a 2.1 percent estimate in September.

To be sure, the Fed is also nearing its neutral rate of interest -- the dividing line between policy that neither spurs nor slows down economic activity.

New York Fed President John Williams has been saying for months that as it reaches that juncture, the direction of future rate increases would become harder to foresee. Powell himself seemed reluctant to say whether policy was easy or tight during his post FOMC meeting press conference, allowing only that it was “appropriate.”

Even if policy is neutral, there’s no clear sign that it’s slowing the job market toward the level the Fed sees as sustainable in the longer run. Employers added a whopping 312,000 jobs in December and economists expect data to show that they tacked on another 165,000 in January. The Labor Department is scheduled to release those figures on Friday.

Officials could be guessing that their four 2018 rate increases will act on the economy only slowly, so restraint will come to bear on employers even rates hold steady. They might think recently-tighter financial conditions will inspire hiring bosses to hold off, and they’re clearly concerned about inflation expectations, which have been coming in at the low end.

But based on Fed officials’ comments over the past year and cautious language around inflation in the December meeting minutes, it seems that they also think low joblessness is not the guidestar for prices -- and therefore interest rates -- that it once was. That gives them room to be patient. Potentially very patient.

“I recently realized a danger in declaring we are at max employment (I find myself doing this too): Every time we think we are there, and then the economy creates a lot of jobs and lures people back in, we then think: well now we REALLY MUST be at max employment,” Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari said earlier this month in a tweet.

“So what do we do?” he asked rhetorically. “Stop trying to assess whether we are at max employment by looking at the unemployment rate” and the employment to population ratio, and “we will know it when wage growth sustainably picks up to levels that, considering productivity, imply future inflation at or above our 2 percent target.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeanna Smialek in New York at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alister Bull at abull7@bloomberg.net, Jeff Kearns

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.