Powell Was Early Spotting Labor-Market Slack, Transcript Shows

Jerome Powell was an early adopter of the view that U.S. unemployment could fall further than thought

(Bloomberg) -- Jerome Powell was an early adopter of the view that U.S. unemployment could fall further than thought, but back then didn’t parlay that insight into a more dovish stance on interest rates.

Transcripts of Fed meetings in 2014 released Friday showed then-governor and now-Chairman Powell was already among the most optimistic Fed officials about how many Americans could be drawn back into the work force as the economy recovered.

Even so, he never took that optimism so far as to call for delaying the eventual liftoff of rates from near zero that began at the end of the following year.

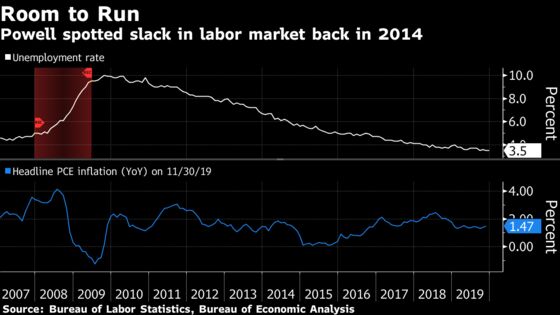

Several times in 2014 Powell declared his belief that unemployment may be able to fall further than staff and other policy makers estimated before triggering an acceleration in inflation. For example, in March he pointed to the Federal Open Market Committee’s median estimate for full employment, then at 5.4% at a time when unemployment was at 6.7%.

“There are good reasons to think that labor-market slack may be even higher,” he said. “I would cite the disproportionate decline of the labor-force participation rate below our estimate of trend and the unusually high level of those who are working part time for economic reasons.”

More Slack

Labor-market “slack” refers to the availability of would-be workers not only among those recorded as unemployed, but also among those who have stopped actively looking for jobs. Their return can translate into higher employment and labor-force participation levels without higher inflation.

That’s exactly what’s happened in the U.S., where unemployment has fallen to a 50-year low of 3.5% but inflation has remained tepid.

Despite that insightful view, which he repeated through the year, Powell’s assessment on the direction of inflation was decidedly more in line with the committee -- based on his judgment that continued job creation would eventually extinguish even his estimates of remaining slack.

“Given these baseline levels of economic growth and unemployment, I have projected a slightly faster return of inflation to the 2% objective,” Powell said in September. “Inflation will turn out to be more responsive to very low and, in fact, negative levels of slack that are in the baseline and in my forecast.”

The transcripts show that even for Fed policy makers open to the idea that the labor market might surprise economists, those same officials were slow to understand how unemployment’s implications for inflation had fundamentally changed.

Powell has been decidedly plainspoken in recent months about that evolution in the Fed’s thinking.

“The connection between slack in the economy or the level of unemployment and inflation was very strong if you go back 50 years and it’s gotten weaker and weaker and weaker to the point where it’s a faint heartbeat that you can hear now,” Powell told Congress in July.

Asset Bubbles

When it came to the 2014 debate on raising rates, Powell may also have been motivated by his nagging concerns about what low rates and stimulative policy could do to financial assets.

In March, even as he shared his optimistic views on slack, he worried about “unsustainably exuberant financial conditions” and said leveraged finance conditions were “in the same Zip code” as “peak-level” ebullience.

A middle course between fueling financial access and avoiding knocking back the recovery involved “rates moving up and volatility returning to normal levels as the economy improves.”

Inflation Expectations

Not all on the committee were so reluctant to try a more aggressively dovish rates policy. Narayana Kocherlakota, then president of the Minneapolis Fed, consistently warned about subdued inflation and the possibility it could cause inflation expectations to slide down, a reality the Fed is dealing with now. Low inflation expectations can drag inflation down even further below target and leave the central bank with less room to fight a recession.

“I am concerned that failing to react to the ongoing subdued inflation outlook has begun to create significant downside risks to the credibility of that target,” Kocherlakota said in the October 2014 FOMC meeting.

Kocherlakota dissented at that meeting and in December 2014, arguing that the committee should commit to keeping rates at zero until inflation returned to 2%. The committee ended up raising rates in December 2015, and eight subsequent times through 2018 before cutting three times in 2019. Inflation has reached the Fed’s 2% target in only a handful of months in that period.

--With assistance from Rich Miller, Matthew Boesler and Craig Torres.

To contact the reporter on this story: Christopher Condon in Washington at ccondon4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Margaret Collins at mcollins45@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull, Ana Monteiro

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.