‘Tone Deaf’ Powell Leaves Wall Street Dazed by Changing Views

The abrupt change in tone highlights the pitfalls of efforts by Jerome Powell, to boost transparency.

(Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, who pledged early in his tenure to speak in “plain English” and improve the central bank’s public communications, is finding it tough to deliver a clear message.

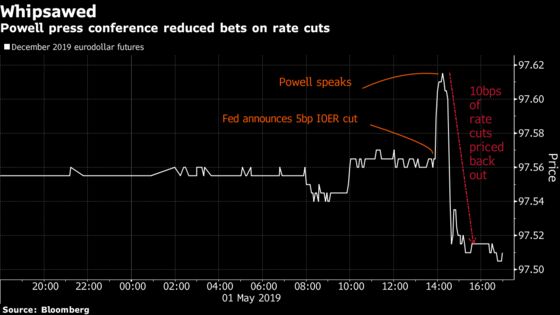

In the latest of several reversals, Powell on Wednesday dismissed the recent deceleration in prices as likely “transitory,” six weeks after he described low inflation as “one of the major challenges of our time’’ risking a Japan-style crisis. The pivot whipsawed financial markets, sending U.S. stocks lower and the dollar higher as traders pared bets that the Fed’s next move would be a rate cut.

The abrupt change in tone highlights the pitfalls of efforts by Powell, 66, to boost transparency. The former private-equity executive doubled the number of annual press conferences this year to eight from the four under predecessors Janet Yellen and Ben Bernanke, who were both economics professors.

Last year, Powell described interest rates as a “long way from neutral’’ and the shrinking of the Fed balance sheet as on “autopilot,’’ two declarations he walked back.

“Certainly relative to Yellen and Bernanke, he tends to give short answers and not a lot of nuance,” said Ethan Harris, co-head of global economics research at Bank of America Corp. in New York. “You are left with half the picture in some cases.’’

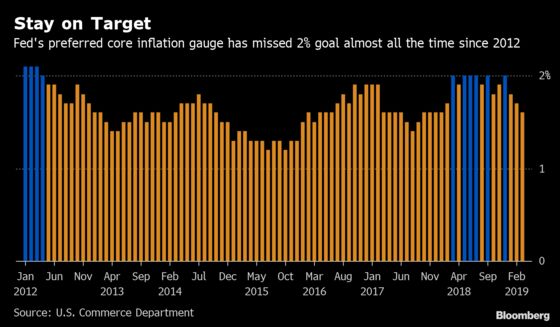

Some investors had been expecting Powell might hint at the possibility of an interest-rate cut, a view that was supported by the release of the Federal Open Market Committee’s statement that highlighted that inflation and core prices, excluding food and energy, were running below the committee’s 2 percent goal.

Instead, Powell pushed back against questions of what might cause the Fed to lower rates, and repeatedly described the issue as temporary. He cited a Dallas Fed measure that excludes high and low readings and pointed to a few categories including portfolio management and investment advice services, clothing and footwear, and air transportation.

Such comments made Powell appear “tone deaf” to market participants, said John Herrmann, director of U.S. rate strategy at Mitsubishi UFJ Securities USA in New York. Herrmann pointed to Powell’s brushing aside a question about then-Chairman Alan Greenspan’s rate reduction in 1995, which led to a record expansion. “He shrugged off that episode,’’ which was “just remarkable.’’

In October, Powell described borrowing costs as “a long way from neutral,’’ then said Nov. 28 that rates were “just below’’ estimates of neutral. In December, Powell seemed inflexible on the balance sheet with his “autopilot’’ comment, followed by the committee in March announcing an end to the winding down of assets.

“Powell may have had a foot-in-mouth moment or two,’’ said Ryan Sweet, head of monetary policy research at Moody’s Analytics Inc. in West Chester, Pennsylvania. “He is less dry than past Fed chairs. There is room for improvement in communications.’’

Of course, some of the issues may involve just learning on the job for Powell, chairman since February 2018.

Bernanke got off to a rocky start in 2006 with an off-the-cuff comment to reporter Maria Bartiromo suggesting the Fed was done raising rates, which he later called a “lapse in judgment.” Yellen, in her first press conference in 2014, said rates could rise in “around six months’’ after bond buying ended, a too-specific description she didn’t repeat.

But they also reflect that Powell, unlike his predecessors, isn’t a Ph.D. economist and is used to the more direct language of a business executive, with fewer caveats. In congressional appearances, he’s been prone to answer questions with “yes’’ or “no’’ as opposed to long-winded explanations that cover all aspects of an issue.

To be sure, there have been shifts in the economic outlook, in part due to delays from the government shutdown.

As recently as the March meeting, forecasters were looking at growth in the first quarter of less than 1 percent rather than the 3.2 percent reported. And the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, excluding food and energy, has dropped to 1.6 percent from about 2 percent in 2018, changes that Powell highlighted in his press briefing.

“The context is important: We have never had so much communication by a first-year Fed chairman,’’ said Diane Swonk, chief economist at accounting firm Grant Thornton LLP in Chicago. “It is not easy when you give real-time analysis and you are chasing a moving target. People are feeling whipsawed but there’s been a whipsawing of economic data too.’’

To contact the reporter on this story: Steve Matthews in Atlanta at smatthews@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alister Bull at abull7@bloomberg.net, Scott Lanman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.