Powell Could Still Get a Rate Cut If He Wanted It — No Matter What the Dot Plot Says

Powell in Position to Overcome Divisions Seen in Fed’s Dot Plot

(Bloomberg) -- Terms of Trade is a daily newsletter that untangles a world embroiled in trade wars. Sign up here.

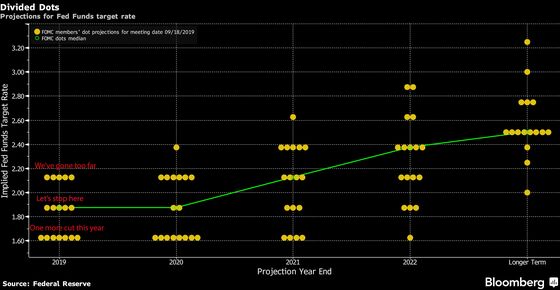

The Federal Reserve’s “dot plot” of interest-rate projections shows plenty of disagreement among central bankers over where monetary policy should go in the next three months.

That doesn’t mean Chairman Jerome Powell will have trouble corralling his colleagues into a another cut in 2019, if that’s ultimately what he wants.

“The dot plot is a very, very imperfect way to understand what’s going on in the committee,” said Narayana Kocherlakota, former president of the Minneapolis Fed and now an economics professor at the University of Rochester. Engineering another 2019 cut “is well within Powell’s ability if he were inclined to make it happen.”

The Fed published its latest dot plot on Sept. 18, the same day officials cut rates for a second time this year. It showed seven of the 17-member Federal Open Market Committee favored even lower borrowing costs by year-end. The remaining 10 indicated the Fed had either reduced rates enough or had already cut too much. The division suggests resistance to further decreases might prove formidable when the FOMC gathers in October and again in December.

A look behind the dots, plus an understanding of the dynamic underlying FOMC voting, suggests otherwise.

For starters, the group of seven looking for another cut clearly included St. Louis Fed President James Bullard and Minneapolis Fed chief Neel Kashkari, the most consistently dovish members of the committee in recent months. Bullard, who even favored a half-point decrease in September, votes this year, so if Powell is convinced there’s a need for another reduction he’s got one supporter in the bag among regional presidents.

It’s also important to consider the pressure on policy makers to show a united front behind Powell.

According to Vincent Reinhart, a former senior staff economist at the Fed, there’s an understanding within the central bank that officials should form a consensus around any policy decision, and that any dissent is essentially a rebuke of the chair.

Regional presidents, who run their own institutions with deep research departments, can more easily resist that pressure than Fed governors if they feel strongly about their policy position. Powell has seen six dissents from regional presidents in just the last three meetings. But a dissent from a Fed governor is far rarer -- there hasn’t been one since 2005 -- and would signal a more serious division.

Same Floor

“It’s tougher if you’re a governor because you work on the same floor, you rely on the chair for committee assignments and access to staff,” Reinhart said. “It also means you couldn’t convince the chair of your view. You’re not in the in-club, and as a governor you should be in the in-club.”

Like the governors, New York Fed President John Williams also has a permanent vote. He’s viewed as occupying a spot in the inner core of FOMC decision making, alongside Powell and Vice Chairman Richard Clarida. A Williams dissent would make big headlines and undermine Powell’s credibility, making it very unlikely.

As a result, the governors, plus Williams, can safely be viewed as a single voting bloc, no matter where their dots fell in September.

“Dots may diverge, votes will converge,” said Carl Riccadonna, chief U.S. economist at Bloomberg Economics.

That means Powell, if he ends up wanting to cut rates again, could open either of the next two FOMC meeting with seven votes, including his own, already in his pocket: the five Fed governors, plus Williams and Bullard.

Evans Vote

Chicago Fed President Charles Evans, a 2019 voter, could be an eighth despite his revelation this week that his dot implies no further cutting this year. He’s viewed as especially dovish over below-target inflation, so if inflation doesn’t rise as he predicts, he could revert. That might leave the two remaining voters, Boston’s Eric Rosengren and Kansas City’s Esther George as the only hawkish dissenters for the third time this year.

It would still be awkward should all the remaining, non-voting presidents line their December dots up with Rosengren and George to reveal a 9-8 split on the committee. But that’s also unlikely.

Powell could probably persuade a few more of his colleagues to lower their 2019 dots, starting with Dallas chief Robert Kaplan, who told reporters on Sept. 20 that he didn’t favor more rate cuts this year but was “open minded.” Atlanta’s Raphael Bostic and San Francisco’s Mary Daly, assuming neither is already in the bottom seven, might also prove accommodating.

So when it comes to predicting the FOMC’s next move, instead of looking for swing voters on the FOMC it’s probably more important to focus on the key policy makers.

“As a Fed watcher, I’m listening to Clarida, I’m listening to Williams and I’m listening to Powell,” said Kocherlakota, who’s also a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. “The dot plot is fun, but I don’t think it’s that meaningful.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Christopher Condon in Washington at ccondon4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alister Bull at abull7@bloomberg.net, Margaret Collins, Scott Lanman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.