Post-Pandemic Economic Puzzle Widens to ‘Phantom Menace’ Rate

Post-Pandemic Economic Puzzle Widens to ‘Phantom Menace’ Rate

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

Global central bankers trying to gauge the threat posed by surging inflation have another puzzle to solve too: whether the pandemic has shifted their policy bearings.

The disruption caused by Covid-19 has been so extensive that economists including Kristin Forbes at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are now wondering if one repercussion could be an increase in advanced economies’ neutral level of interest rate -- the setting at which growth is neither stimulated nor constricted.

If that equilibrium point -- sometimes called R* -- has drifted higher, that would mean central banks’ already ultra-easy monetary policy is looser than generally thought.

While that offers the prospect that officials may need to repeatedly raise interest rates in due course to brake the economy, it also holds the risk that they misjudge how stimulative their stance is. Such a policy error could open the door to an enduring bout of inflation.

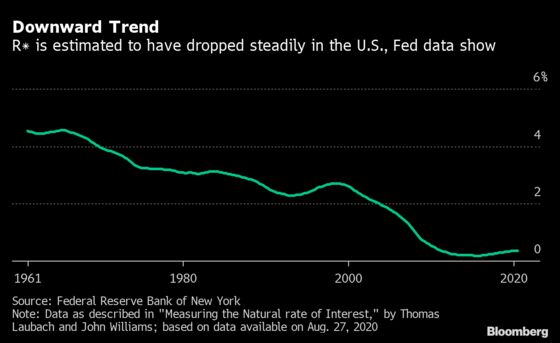

Economists including New York Federal Reserve President John Williams have long judged R* to have plummeted since the turn of the millennium, citing forces such as demographics or productivity growth.

Factors that might reverse that now include a sudden shift toward digitization, a wave of innovation, structural labor-market changes, massive fiscal stimulus, and a wholesale return of risk appetite.

“Just because it has fallen in the past, we don’t know where it’s going, and there’s a good chance it could pick up again,” said Forbes, an MIT professor and a former external member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. “Everyone talks about the long-term decline like it will last forever, and I think the risks are two ways.”

Forbes touched on the topic last month at the Kansas City Fed’s annual Jackson Hole symposium. The event also featured a paper concluding that worsening income inequality in the U.S. has been a key factor in the decline of R*, rather than demographics.

Such discussions underscore how identifying the forces driving the metric remains a matter of academic debate, just as views also differ on how to calculate it.

In the U.S., Deutsche Bank AG economists reckon the rate has fallen almost to zero. Fed officials are taking a wait-and-see approach, according to the median estimate of quarterly Federal Open Market Committee projections, which has assessed R* at 0.5% on an inflation-adjusted basis since mid-2019.

A model maintained by the New York Fed suggested it was probably at 0.36% in June 2020, its last estimate before calculations got suspended due to big output swings caused by the pandemic.

Such is the rate’s elusive nature that in 2018, St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard, in arguing that the level was likely to stay persistently low, resorted to the Star Wars analogy of “the phantom menace” to describe R*.

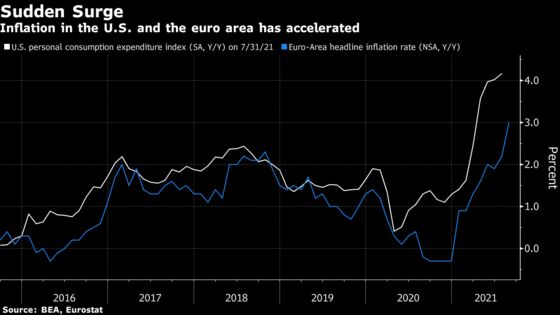

Central bankers use the gauge in judging whether their policy stance is appropriate to generate the right amount of inflation. That’s pertinent now as officials on both sides of the Atlantic confront rising consumer prices, which they currently attribute to temporary factors such as transportation bottlenecks.

It’s the pandemic’s impact on the structure and potential of economies that raises the prospect that R* has shifted. On productivity, for example, there’s tentative evidence that years of slowing expansion may have reversed, aided by remote working and digitization.

McKinsey Global Institute research estimates productivity growth in the U.S. and Western Europe could increase by about 1 percentage point annually in the years to 2024, more than doubling the pre-pandemic pace.

Lasting workforce changes, for example from women dropping out to home-school children during the crisis, might also have helped lift the neutral rate.

Dario Perkins, an economist at TS Lombard in London, wonders if the pandemic actually even initially depressed R* further, but he now reckons it’s rising again with the tailwind of wholesale fiscal stimulus.

“First we need to get back to where we were,” he said. “Beyond that, you can see the signs of a gentle inflection point, but it’s going to be very reliant on governments’ spending.”

Longer term, an aging workforce across industrialized countries might mean a smaller supply of labor and a lower demand for savings as people leave jobs for retirement. Budget deficits and the expansion of credit to the private sector also could weigh on savings.

“I now believe that the global saving glut may be ending,” said Philip Turner, a visitor at the London-based National Institute of Economic and Social Research and previously an official at the Bank for International Settlements. “This would mean that the equilibrium real interest rate needed to hold back inflation has risen.”

Inflation Path

The path of inflation itself will help determine how much a higher R* actually matters for central bankers. While the BIS is among those observing little evidence of labor costs picking up enough for people to start expecting price increases down the road, wages in the U.S. and the U.K. have begun to rise as firms struggle to attract workers.

Concerns about such pressures have yet to take hold among investors however, even though risk aversion is now far less pronounced than it was earlier in the pandemic.

“What the market is telling us is that we have that savings absorption problem, implicitly telling us that the neutral real interest rate in the industrial world, even in the face of very large real interest rates, is going to be significantly negative,” former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, a paid contributor to Bloomberg, said during a panel discussion on Sept. 2.

Longer term, however, lower demand for safe assets such as government bonds as the Covid crisis abates “should push the natural rate up,” said former European Central Bank Chief Economist Peter Praet, though he doubts more powerful factors like productivity growth or demographics will have much of an influence imminently.

If Atif Mian, Ludwig Straub and Amir Sufi, authors of the Jackson Hole paper, are right about inequality being a big driver, the worsening gap between the “haves” and the “have-nots” caused by the pandemic would mean R* isn’t likely to rise soon at all.

“Are we going to see a reversal in the coming years? There are some indications, but I would not bet too much on this,” Praet said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.