Pimco Joins Chorus of Negative Rate Detractors as Backlash Grows

Pimco Joins Chorus of Negative Rate Detractors as Backlash Grows

(Bloomberg) --

Bond powerhouse Pacific Investment Management Co. has become the latest high-profile critic of negative interest rates, warning that one of the key central-bank tools in economically beleaguered Europe and Japan may do more harm than good.

In a report published Tuesday, Pimco noted three key drawbacks of sub-zero rates. They squeeze the profitability of banks and thus might actually reduce lending; they depress market returns and create “significant challenges” for pension funds and insurers that offer guaranteed payouts; and they create a “money illusion” in which savers feel poorer and thus cut consumption.

While those criticisms have long been leveled at institutions such as the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan, the voice of Pimco -- with $1.9 trillion of assets under management -- adds to a rising clamor. Goldman Sachs Chief Executive Officer David Solomon called them “a failed experiment,” and even central bankers have started expressing concerns about the side effects.

“The unintended consequences of negative interest rate policy are already evident,” portfolio managers Nicola Mai and Peder Beck-Friis wrote. It “doesn’t have much further room to run.”

Economic theory suggests that cutting interest rates below zero should have a similar expansionary effect to reducing them in a positive-rate environment. It should incentivize people to save less and spend more, boosting growth and inflation.

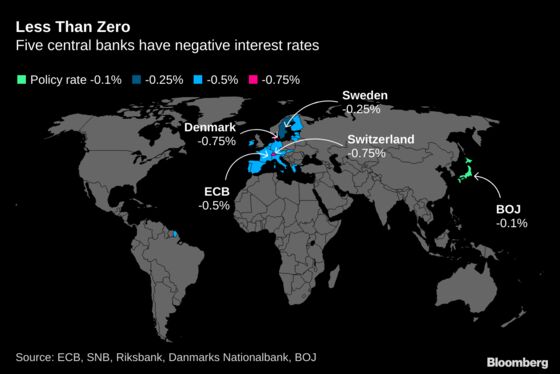

In practice, the researchers found that while subzero rates initially helped ease financial conditions and boost lending, especially in the euro area, that impact has been spent. The ECB is one of just five central banks with such a policy, along with those of Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark and Japan.

Trouble Brewing

Pimco said “significant trouble is brewing under the surface” at banks, which must pay to central bank to hold reserves but can’t easily pass the cost on to customers. Deutsche Bank AG President Karl von Rohr said last month that the region’s banks and insurers “have lost dramatic amounts of ground” to competitors, with only one still ranking in the top 20 globally by market value, compared with six before the global financial crisis.

In Japan, where the policy rate is minus 0.1%, Governor Haruhiko Kuroda is finding it increasingly hard to get support from the country’s “Shinkin” regional cooperative banks, which rely heavily on deposits for funding.

In an attempt to boost their returns, investors are chasing riskier assets which might prove to be harder to sell. That’s a particular worry for pension funds, which are often required by law to guarantee a certain level of payments to retirees. Pimco warned of instability and potential capital injections if they fail to deliver.

Finland’s Ilmarinen Mutual Pension Insurance Co., with $55 billion in assets, says it’s buying fewer easy-to-selll assets, a sign that liquidity has become a luxury of a bygone age. The Dutch finance minister said the ECB’s September venture deeper into negative territory could have “huge consequences for a lot of things that we think are important.”

Only last week, Sweden’s financial watchdog proposed adding $1.6 billion to the capital requirements of the nation’s three biggest banks and said the system “is becoming exposed to new risks that we haven’t really thought of before.”

The country’s central bank, the Riksbank, has had enough, signaling that it intends to raise its key rate to zero from minus 0.25% this month. It’s a move sure to be watched by its peers, who have continued to defend negative rates as a necessary stimulus tool while also becoming worried about the threat to financial stability.

The ECB, where several policy makers were dubious about the September stimulus package, is about to launch a review of its own monetary policy under new President Christine Lagarde.

Meanwhile, depositors are ever more fearful. German media have used front-page imagery to portray the ECB has sucking savers dry. Banks in Denmark, which along with Switzerland has the world’s lowest policy rate at minus 0.75%, are increasingly passing the cost onto retail customers. Once taboo, that strategy might become standard.

Pimco said it found “some signs that household saving rates have risen in some countries” -- in contradiction to what negative-rate theory would predict. Other nations, viewing the experiment in Europe and Japan, are reluctant to make the leap.

Trump’s Wish

Bank of England Governor Mark Carney has said he doesn’t see negative rates as part of his toolkit. In the U.S, despite President Donald Trump’s repeated claims that the Federal Reserve should have the world’s lowest rates -- and a weaker currency -- policy makers are unwilling to do his bidding.

Chair Jerome Powell said last month that negative rates would “certainly not be appropriate in the current environment.” Among his colleagues, Neel Kashkari said negative rates would be a last resort in a downturn and Eric Rosengren said he wouldn’t want to go that far in the next recession.

Pimco said that for countries already below zero, there’s no easy way out and global rates will remain anchored. That means investors will keep taking on more and more risk.

“Investors are forced to ‘reach for yield’ – even if such a move may be damaging in the medium or long term,” the report said.

--With assistance from Nicholas Comfort.

To contact the reporter on this story: Piotr Skolimowski in Frankfurt at pskolimowski@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, Brian Swint

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.