Pandemic Scenario May Mean Revisiting ECB’s Maxed-Out Tools

Pandemic Scenario for ECB May Mean Revisiting Maxed-Out Toolkit

(Bloomberg) -- If the coronavirus outbreak morphs into a regional economic crisis, the European Central Bank isn’t yet poised to rush to the rescue.

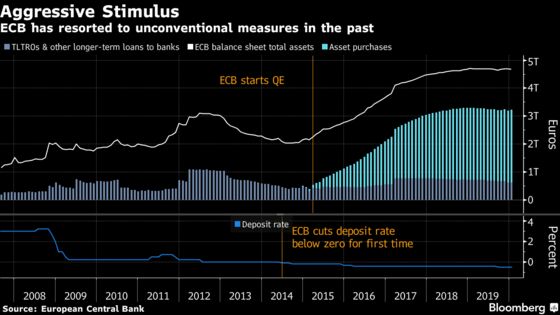

With interest rates deep below zero and the latest batch of asset purchases still ongoing, room for additional monetary support is severely limited even as money markets now see a cut in borrowing costs later this year. For policy makers in Frankfurt, that makes their case for governments such as Germany’s to deliver the next big push for economic growth all the more persuasive.

“The ECB is not fully maxed out, but it’s getting close,” Anna Titareva, an economist at UBS Group AG, told Bloomberg Television. “The threshold to provide more policy accommodation remains quite high.”

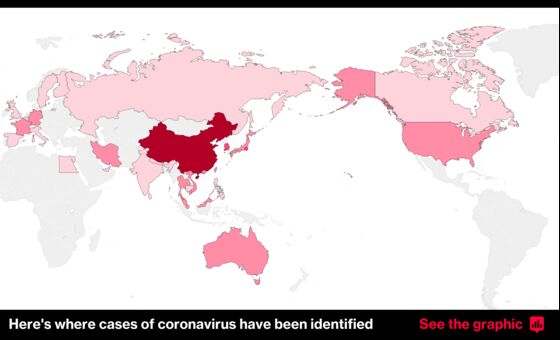

The ECB might ultimately not have the luxury to wait for fiscal help, if the disease that’s already infected more than 80,000 people worldwide and claimed nearly 3,000 lives turns into a global pandemic -- and a recession so far isolated in manufacturing engulfs the broader economy.

Such a scenario would make ECB President Christine Lagarde’s warning in January not to assume that policy is on autopilot all the more prescient. Just one month after she spoke in Davos, a problem that seemed far away in China is now uncomfortably close to home after a major outbreak in Italy.

Here are some options for Lagarde and her colleagues to consider as the impact unfolds. The Governing Council holds its next policy meeting on March 12.

Phone Berlin

ECB officials might first simply call on governments in Berlin and around the 19-nation region, urging fiscal spending from those who can afford it. They could argue that tax breaks and public investment may be more effective than monetary policy in encouraging consumption and offsetting weak exports.

Policy makers including Ignazio Visco and Francois Villeroy de Galhau -- the governors of the Italian and French central banks -- have already insisted that the burden should be on leaders to reboot economies. However, previous calls for coordinated spending have triggered only silence so far.

Soothing Words

Policy makers may resort to words in an initial attempt to shore up confidence, promising to carefully watch over the economy and tailor action to the specific problem at hand.

The ECB previously laid out contingencies in 2014 before starting quantitative easing the next year. The tactic brings the advantage of assuring companies and investors that officials are fully attuned to their problems, and buys time to see if any crisis ebbs on its own. Austria’s Robert Holzmann said Wednesday that while the virus will leave its mark on the economy, he doesn’t expect long-term problems.

Another Cut

The ECB insists it can still lower the deposit rate if needed, and Chief Economist Philip Lane sees no impediment to that even after more than half a decade of negative borrowing costs. Rabobank economists note that the institution’s exemption of some deposits when it trimmed the rate to -0.5% in September implicitly created room for further reductions, and financial markets are now betting on a 10 basis-point cut in December.

In reality though, policy makers currently have no apparent appetite for that. Visco and Villeroy have been among the most outspoken critics, citing concerns over eroding bank profitability. Another cut could also stoke outrage among German and Dutch savers, providing fodder for populist parties.

More QE

While turbo-charging quantitative easing might be less politically toxic, it’s still controversial, particularly among monetary-policy purists like Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann.

The current program, which runs at a monthly pace of 20 billion euros ($22 billion), has effectively been designed to last through 2021, even though it has no official end date. Increasing monthly purchases or continuing for longer could test a self-imposed rule, intended to avoid monetary financing, that the ECB can’t buy more than a third of each government’s debt.

How officials tailor QE would ultimately depend on the sort of hit the economy endures. For example, a spike in sovereign yields reflecting doubts in governments’ ability to contain the crisis could force extra government bond purchases. If company financing is the problem, one option is to buy more corporate debt. The ECB might even conceivably consider new assets such as bank bonds, or borrow a page from the Bank of Japan’s playbook and buy stocks.

Liquidity Tap

A less controversial tool would be to simply flood the financial system with money to prevent funding tensions. Yet with some 1.7 trillion euros in excess liquidity already in the system and banks able to tap the ECB for unlimited short-term cash, demand might be lacking.

Alternatively, the Governing Council could make their long-term loans more favorable, lengthen maturities from the current three years, or offer more operations beyond March 2021, when the last so-called TLTRO is scheduled. If banks’ access to currencies other than the euro is hurt, the ECB could also dust off swap lines with central banks including the Bank of England, the Swiss National Bank, the Federal Reserve and the People’s Bank of China.

--With assistance from Matthew Miller, Anna Edwards and Dana El Baltaji.

To contact the reporters on this story: Jana Randow in Frankfurt at jrandow@bloomberg.net;Piotr Skolimowski in Frankfurt at pskolimowski@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Fergal O'Brien at fobrien@bloomberg.net, ;Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, Craig Stirling

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.