Nordic Data Debacles Tell Story of Numbers That Aren’t True

Nordic Data Debacles Tell Sad Story of Numbers That Aren't True

(Bloomberg) -- Explore what’s moving the global economy in the new season of the Stephanomics podcast. Subscribe via Apple Podcast, Spotify or Pocket Cast.

Scandinavia is offering a fresh case study this month in how even the world’s richest countries can struggle to measure their own economies.

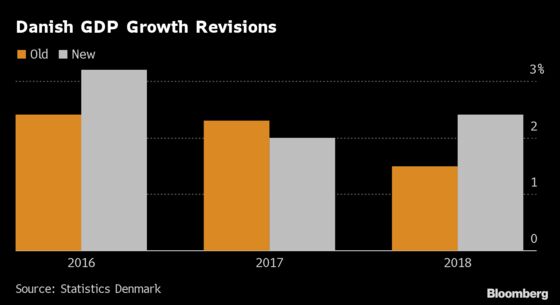

On Nov. 7, Danish statisticians revised growth estimates for the past three years, the latest in a series of reassessments that cumulatively added 93 billion kroner ($13.7 billion) in previously “unaccounted for” gross domestic product. Meanwhile, the Riksbank lashed out last week at Sweden’s number-crunchers for what it described as a “catastrophic” overestimation of unemployment.

Such frustration might seem reminiscent of the problems of poor visibility faced by policy makers in less developed countries, where data collection might be closer to guesswork. But both episodes also illustrate that -- despite high expectations placed on statisticians -- gauging an economy’s size, health and workforce in the age of globalization and the internet is no easy task.

“There’s a fundamental problem, in that the data are estimates,” said Stefan Gerlach, a Swede who was formerly deputy governor of the Irish central bank and is now chief economist at EFG Bank AG in Zurich. “But they’re often treated as truths.”

Outdated Concepts

Measuring growth in particular showcases the challenge for statistics agencies. Charlie Bean, a former Bank of England deputy governor who led a review of U.K. economic data, notes that the concepts underpinning GDP date from around World War II, when services didn’t matter so much.

“Most of the economic activity was production -- producing physical stuff,” he said in an interview. “What we’re trying to measure has become a much more slippery concept.”

The Danish GDP example reflects that. Revisions came about because preliminary growth estimates were provided based on incomplete information from multinational corporations based in the country.

“These problems are of course the result of a much more global society,” said Jorgen Elmeskov, director general at Statistics Denmark.

Denmark is far from alone. Ireland, another small, export-oriented country reaping the rewards of globalization, saw GDP balloon by an eye-watering 26% in 2015, simply because the intellectual property of corporations like Google and Facebook got included in its output calculation after they moved there. It led economist Paul Krugman to famously coin the term “leprechaun economics.”

China offers another case in point. On Friday it revised its GDP data for 2018, adding the equivalent of Finland’s output to its economy.

Diane Coyle, an economist and professor at Cambridge University, reckons expectations on GDP data are just unrealistic.

“People believe that it’s a real thing, like it’s a mountain you’re trying to measure how high it is,” she said. However, “it’s a concept. The definitions change and the assumptions that statisticians make change too.”

She cites consumer prices as facing similar challenges. That’s an issue experienced in Sweden, where a decade ago, then-Finance Minister Anders Borg said an error in the calculation of shoe prices cost the government tens of millions of dollars in lost tax revenue and extra social security benefits.

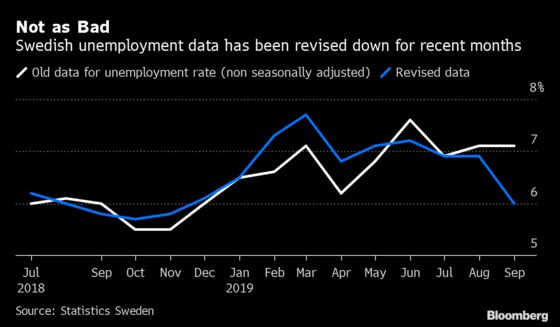

Sweden’s unemployment miscalculation also shows the degree to which statistics agencies are struggling to measure evolving economies with limited resources. To save costs, officials had outsourced measurement of joblessness to a subcontractor, leading to the errors subsequently condemned by Riksbank Deputy Governor Henry Ohlsson.

“Public statistics are the basis for economic, political decision making,” he said. “This is a sad story.”

Tense Debate

His fury may reflect a critical juncture for the Riksbank. The revisions coincide with a tense debate on whether the central bank is right with its intention to raise interest rates as soon as next month, just as the economy appears to be slowing.

Policy makers must often live with such obstacles however. In 2006, then-Bank of England Governor Mervyn King complained that he and his colleagues, including Bean, just didn’t know how big the U.K. population was, because of flawed counting of a record wave of immigration. That distorted their view of the labor market and hampered decision-making.

Thirteen years later, U.K. statisticians are still struggling to keep count, admitting in August that immigration was continually being underestimated in the same survey King had lamented.

Gerlach of EFG says the moral for everyone, not least central bankers, is to take economic data with a pinch of salt.

“There’s much more uncertainty about the economy than you think,” he said. “That needs to be kept in mind part when you discuss things like monetary policy.”

| Read more... |

|

--With assistance from Rafaela Lindeberg, Niclas Rolander and Morten Buttler.

To contact the reporters on this story: Nick Rigillo in Copenhagen at nrigillo@bloomberg.net;Catherine Bosley in Zurich at cbosley1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Christian Wienberg at cwienberg@bloomberg.net, ;Fergal O'Brien at fobrien@bloomberg.net, Craig Stirling, Zoe Schneeweiss

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.