No Mere Crisis Will Convince Germans to Fall in Love With Debt

Just because Germany has embraced a massive fiscal binge for the coronavirus crisis, don’t assume they have changed their ways.

(Bloomberg) -- Just because Germany has embraced a massive fiscal binge to address the coronavirus crisis, don’t assume the country has suddenly changed its ways.

In the nation whose budget prudence used to be the scourge of economic policy makers from Frankfurt to Washington, some politicians are already plotting how to reinstate parsimony when the bad times are finally over.

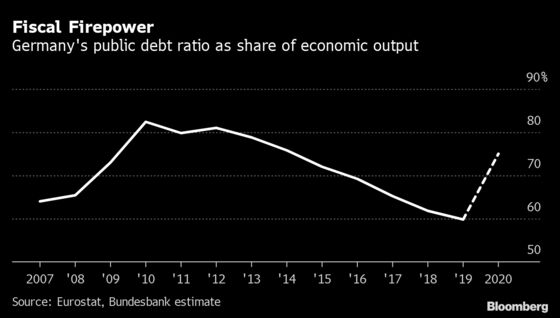

Far from marking a new approach in Europe’s biggest economy, the deployment of stimulus and aid for the Covid-19 emergency is being showcased as the justification for a public-finance framework that endorsed balanced budgets to store up fiscal firepower for a crisis.

Chancellor Angela Merkel reflected that mood last month as she expressed satisfaction that Germany didn’t previously succumb to the “sweet poison” of debt. Such a mantra will probably bind whoever succeeds her at the helm of the CDU party in due course.

“There is a notion that the German government was able to implement this supercharged fiscal support because it had room for maneuver in the first place,” said Katharina Utermoehl, a senior economist at Allianz SE in Frankfurt. “If anything, fiscal prudence is still in fashion.”

That commitment might be hard to discern at first from the government’s fiscal plans for 2021, which Social Democrat Finance Minister Olaf Scholz will set out in draft form later this month. He has privately floated a potential 80 billion-euro ($94.4 billion) budget deficit next year.

Black Zero

Such a shortfall would add to borrowings of 218 billion euros for 2020, to fund measures ranging from a value-added tax cut to extra money for parents. Germany has also deployed its budget muscle for a European recovery fund that could form the basis of future fiscal union.

To pay those bills, Scholz’s deputy, Werner Gatzer, has cautioned that the country shouldn’t seek to return soon to the so-called “black zero” balanced budgets achieved during much of the past decade.

But despite the semblance of a new-found love for borrowing, government officials insist they remain completely committed to fiscal prudence.

“While Germany is now taking on new debt, this will not open the floodgates,” said Andreas Laemmel, a lawmaker from the CDU, which rules in a coalition with its Bavarian CSU sister party and the Social Democrats that Scholz belongs to. “As long as the CDU/CSU is in government, there will be no paradigm shift in debt policy.”

That formal stance may belie the pragmatism that characterizes Germany’s expansive policy at present. But it could also face a challenge if the outcome of next year’s election empowers the more spending-focused Greens with a seat in government, or in the unlikely event that the CDU is cast into opposition.

Debt Brake

Even then, the country’s constitutionally enshrined debt brake would be hard to shake off as a lodestar of fiscal policy. The measure limits governments to a structural deficit of 0.35% of gross domestic product during good times.

In a glimpse of the political determination to hold to that doctrine, Scholz is currently being pressured by the CDU/CSU alliance to present a plan on how the brake will become fully operational again with a view to achieving that by 2022 at the latest, according to people with knowledge of the discussions.

The fiscal rule has long been a frustration to the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank, which before the crisis regularly called for countries with available budget space to use it to spur economic growth.

Some German economists such as Marcel Fratzscher, head of the DIW Institute in Berlin, also insist that the brake is a straitjacket on economic growth that avoids borrowing purely for the sake of a principle.

“When the recovery takes hold, we’ll be back to the old debate about how much debt makes sense,” said Christoph Schmidt, President of the RWI Leibniz Institute for Economic Research in Essen. “This is going to be an intense debate, also within Europe.”

Germany’s fiscal framework remains popular, in a country where the word for “debt” also means “guilt.” Christian Odendahl, the Berlin-based chief economist of the Centre for European Reform, says if attitudes do end up changing over time, that’s likely to be motivated by more everyday concerns than the coronavirus crisis.

“If you start asking people now about public investment, whether they would like better infrastructure or faster internet, you see some shift there,” he said. “Some people in Germany would be more willing to tolerate higher debt for public investment. But it’s a slow process.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.