Mysterious Demise of the Phillips Curve Is Weirdest in Australia

Australia's Wage Growth Worries the World's Central Bankers

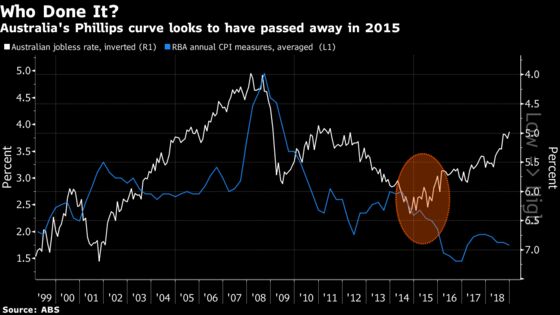

(Bloomberg) -- The traditional relationship between inflation and employment has faltered in much of the developed world -- nowhere more so than in Australia where it’s seen an unprecedented breakdown in the past few years.

The Phillips Curve suggests tight labor markets should force firms to raise wages, and they in turn raise product prices to cover the costs. That means low unemployment should result in faster inflation, or so the theory goes.

Reserve Bank of Australia chief Philip Lowe this month said the subject is a constant source of discussion among his counterparts.

“Whenever I go to Basel, which I do six times a year to talk to the governors of the other central banks, it was the most commonly discussed issue,” Lowe said following a speech in Sydney. “Why in tight labor markets, wage growth isn’t picking up. So what’s happening in Australia is really a global story.”

The latest chapter of that tale will be written in data this week. Fourth-quarter wages data Wednesday showed a steady year-on-year pace of 2.3 percent while January’s jobs report due Thursday is set to show unemployment remained at 5 percent, according to economists surveyed by Bloomberg.

Among developed nations, only Denmark comes close to the divergence seen in the chart above, but nowhere near as pronounced. Part of the reason comes down to the timing of the anomaly’s emergence in Australia, historically an inflation-prone economy.

Unlike many developed-world counterparts, Australia’s employment and inflation relationship remained relatively intact after the 2008 crisis as an investment rush to meet demand for resources from China kept the economy powering along. As the mining boom wound down and commodity prices slid in 2015, a funk took hold that’s only deepened since.

The early thinking was that the economy was regaining competitiveness: after a decade of unprecedented investment and digging up iron ore to ship to China, wages had probably risen further than justified. In the new straitened times, the economy needed to work off some of its flab; similarly, the currency needed to depreciate to reflect the economy’s real place in the world.

To aid the transition, the RBA cut its cash rate to a record-low 1.5 percent in 2016, aiming to encourage firms to invest and hire in the expectation that the Phillips Curve would reassert itself. But while unemployment fell -- it’s now 5 percent, and closer to 4 percent in major cities -- wages stagnated and inflation remained subdued.

Philip on Phillips

Lowe’s take is that we are likely in a new normal, where unemployment needs to fall further to drive wage growth. Other global central bankers have come to the same conclusion.

The explanation, he says, lies with people reacting to increased competition -- via technology and globalization -- and uncertainty about the future. Yet the governor maintains supply and demand still work.

“At some point, I haven’t given up on the idea, that as the labor market tightens and firms start competing more aggressively for workers, wages will move,” he said this month.

He counsels patience and argues it’s already happening, gradually. Whether he’s right or not will go a long way to determining whether his next interest-rate move is a hike or cut.

To contact the reporters on this story: Michael Heath in Sydney at mheath1@bloomberg.net;Garfield Reynolds in Sydney at greynolds1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nasreen Seria at nseria@bloomberg.net, ;Malcolm Scott at mscott23@bloomberg.net, Chris Bourke

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.