MMT Has Been Around for Decades. Here’s Why It Just Caught Fire

MMT Has Been Around for Decades. Here’s Why It Just Caught Fire

(Bloomberg) -- Over a lifespan of about three decades, Modern Monetary Theory has often been badmouthed -- by obscure bloggers. Not by the likes of Jerome Powell and Larry Fink.

Ignored for years, MMT suddenly finds itself at the center of America’s economic debate, raising the question: why now? Here are some possible answers.

Already in Deficit

The theory’s headline argument is that governments with their own currencies have more room to spend than is generally supposed, and don’t have to finance it all with taxes. According to this view, there’s no risk of the U.S. being forced into default, because it can create the dollars it needs to meet any obligations.

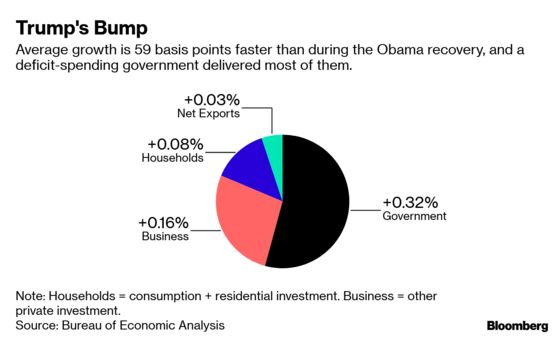

The claim may look less contentious today because the U.S. has already been piling up public debt for a decade. The initial surge came out of crisis firefighting, a fairly orthodox response to the Great Recession. But fiscal stimulus is now being used to make an already expanding economy grow faster -- on a scale that hasn’t been tried since the 1960s.

That’s why advocates say MMT shouldn’t be seen as a policy package that might get adopted one day. Instead, it’s more like a framework for understanding what tools are available to a government. And some of those tools are already being used.

Easy Markets

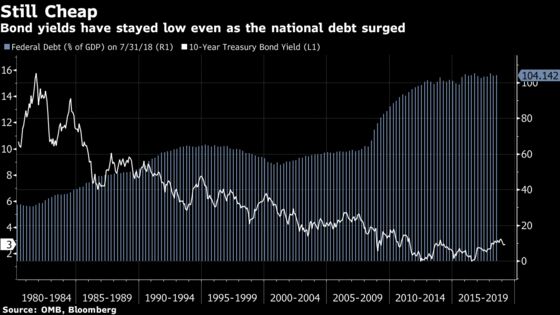

“Deficits are going to be driving interest rates much higher,” BlackRock Inc. Chief Executive Officer Fink said last week, describing MMT as “garbage.”

Sentiment can swing on a dime, but investors are currently relaxed about all the red ink. The U.S. budget gap has already blown past 4 percent of GDP. It’s forecast to keep widening at least through 2021. Yet the government can borrow 30-year money at about 3 percent. There’s no shortage of people warning about deficit dangers, but the markets aren’t joining in.

No Inflation

The theories leaned on by policy makers since the inflationary 1970s have primarily focused on achieving price stability. But the standard models they use, which view inflation as at least partly a function of the unemployment rate, seem to have broken down. Record-low jobless numbers in the U.S. should be stoking prices, but they aren’t.

As a result, economists have been losing confidence in ideas that 25 years ago seemed obvious. And with a generation having passed since inflation looked like a serious problem, the case for fighting it as public enemy number one has weakened too. That’s opened the door for frameworks geared more toward addressing 21st-century concerns such as rising inequality -- more extreme in the U.S. than in any other developed country -- or America’s lack of a universal health-care safety net.

The Trump Factor

Politically, the MMTers tend to lean left -- but they insist their ideas are applicable by a government of any stripe. And they sometimes express a sneaking admiration for Donald Trump’s approach to fiscal policy, because the president appears to pursue his real-economy goals (lower business taxes, more military spending) and worry about budget outcomes later.

“I don’t think good growth policies have to obsess, necessarily, about the budget deficit,” Trump’s economic adviser Larry Kudlow said on Sunday. That’s pretty much what MMT would advise -- even if most of its adherents disagree with Trump’s economic goals and would spend the deficits very differently.

The AOC Factor

It was Senator Bernie Sanders who opened the door for MMT into U.S. politics. He hired Stephanie Kelton, the economist and Bloomberg Opinion columnist who’s become the public face of the doctrine, first at the Senate Budget Committee and then as an adviser during his 2016 tilt at the presidency. Sanders sometimes nodded toward MMT by saying America needs to address real-economy deficits in infrastructure or education as well as financial ones in its budget. But he never endorsed it explicitly.

Freshman Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, who also worked on the Sanders campaign, has done so. She’s said MMT should be “a larger part of our conversation” and urged Congress to use deploy its “power of the purse.” Ocasio-Cortez has millions of followers on social media, where economic and political ideas are spread.

Big in Japan

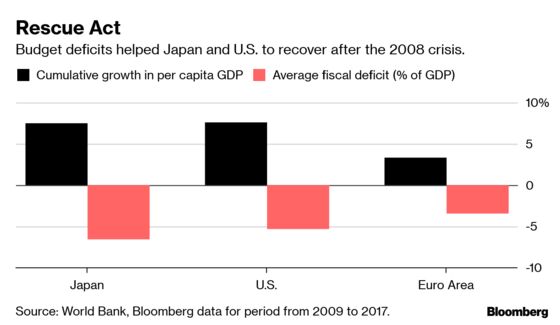

The country that’s probably come closest to deploying the full MMT toolkit is Japan, where interest rates hit zero 20 years ago and public debt -- partly financed by the central bank -- is now almost 2 1/2 times the size of the economy.

Japan isn’t growing quickly, but its image among Western economists as some kind of basket-case has been undergoing a rethink. Serial deficits haven’t triggered inflation or a flight from bond markets. And real incomes have kept pace with America’s (and exceeded Europe’s) since 2008.

The Mainstream Has Moved

Big-name economists from top U.S. universities are lining up to denounce MMT. “Fallacious at multiple levels,” Harvard’s Larry Summers called it. Others to join the attack include Nobel laureate Paul Krugman and Olivier Blanchard, the former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund.

At the same time, it’s become more common to see these same high-profile liberal economists coming out in favor of deficit-spending, and dismissing concerns about the national debt as overblown. Summers, Krugman and Blanchard have all made that case in recent weeks -- even while arguing that MMT gets the mechanics wrong.

To contact the reporters on this story: Ben Holland in Washington at bholland1@bloomberg.net;Matthew Boesler in New York at mboesler1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Kennedy at skennedy4@bloomberg.net, Ros Krasny

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.