Made-in-Germany Growth Engine Falters as Firms Hit Supply Shocks

Made-in-Germany Growth Engine Falters as Firms Hit Supply Shocks

(Bloomberg) -- Supply Lines is a daily newsletter that tracks trade and supply chains disrupted by the pandemic. Sign up here.

The engine of the German economy is turning into a brake in the face of a global supply crunch, threatening to derail the nation’s recovery.

While its strong focus on manufacturing helped Europe’s largest economy fare better than its more service-heavy peers in the region during Covid lockdowns, Germany’s rebound is now at risk as companies report shortages of materials ranging from memory chips to lower-tech parts and even basics such as wooden pallets.

Pandemic jolts to economies everywhere are throttling even a Germany Inc. brand built on efficiency and a reputation for precision and durability. The supply problems are wreaking havoc on companies from Siemens AG to BMW AG, and they could persist into next year or even longer.

“In my career we haven’t had a situation with so many commodities being scarce at the same time, and I’ve been dealing with the same materials since 1996,” said Thomas Nuernberger, managing director of sales at Mulfingen, Germany-based EBM Papst, a maker of industrial fans. “This is the most difficult situation in the global supply chain I’ve witnessed.”

Siemens CEO Roland Busch earlier this month warned that risks including the global semiconductor shortage, along with rising raw-material and freight costs, pose headwinds that are “likely to prevail into fiscal 2022.”

Nuernberger sees the disruptions dragging on, too. “I count on growth being delayed until 2023, because even in 2022 we will still have problems with semiconductors” and the container shipping turmoil “will also last well into 2022,” he said in an interview.

Falling Short

Such concerns add to a warning from Germany’s central bank, which said last week that growth this year may fall short of the 3.7% it forecast in June, partly due to the supply problems.

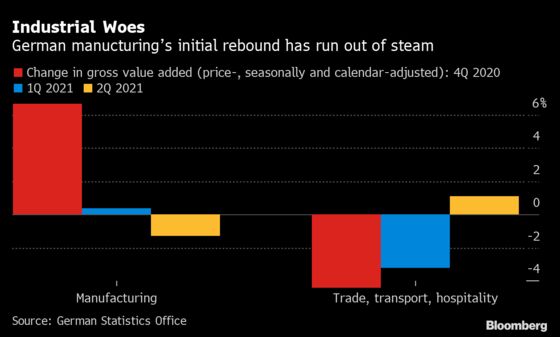

According to Bloomberg Economics, German factories were still operating around 7% below their pre-pandemic level as of June, with automakers and machinery manufacturers particularly lagging behind.

“Things are actually getting worse rather than better,” said Clemens Fuest, president of the Munich-based Ifo institute.

The institute’s business confidence index dropped more than economists forecast in August, and Fuest expects growth this year will be weaker than previously expected.

There’s a political backdrop on top of the economic fallout. Germany is preparing for elections in less than a month that will see the winner succeed Chancellor Angela Merkel after her 16 years in power.

Key to how things will pan out is Germany’s dominant car industry, which has been hampered by the global shortage of semiconductors.

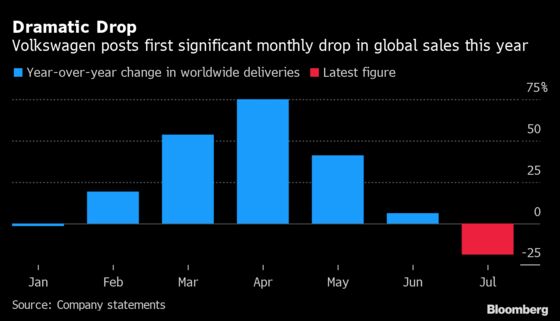

After holding up relatively well in the first half, Volkswagen AG Chief Executive Officer Herbert Diess said on Bloomberg TV recently that Europe’s largest automaker was “going to see some hits in the third quarter because production now is really constrained.” The company’s worldwide vehicle deliveries plunged 19% in July, its first significant monthly drop this year.

VW’s Wolfsburg plant -- the world’s biggest, employing some 60,000 people -- restarted from its usual summer break operating on only one shift. Audi, the group’s biggest profit contributor, also extended the summer recess at its two factories in Germany by a week.

There have also been warnings from Daimler AG and BMW, with both citing the dearth of chips.

Yet the supply problems are far from confined to the auto industry. A survey by the Association of German Chambers of Industry and Commerce, among some 3,000 firms across various sectors showed 83% of them reeling from rising prices or shortages of components and raw materials. The majority doesn’t expect things to get better this year.

Adidas AG and Puma SE, for example, have been hit by plant closures in Vietnam after Covid-19 outbreaks there. Ports, meanwhile, are backed up from Shanghai to Hamburg. Publishing houses are reported to be short on paper and other materials used to produce books.

Niche Producers

And with many small- and medium-size companies in Germany focusing on niche markets, it’s hard for them to find alternatives quickly if their usual supply routes fall flat.

“We’re mostly specialists,” said Ralph Wiechers, chief economist at the German Machinery Industry Trade Association. Many companies are producing small series or even tailor-made machines in close cooperation with their suppliers, a process that can “take years to adjust,” he said.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“Despite a surge in orders, Germany’s industrial recovery has been hampered by severe supply disruptions. We anticipate the industrial sector to start contributing positively to growth from 3Q. True enough, advances are likely to be gradual and bumpy, but as services continue to respond swiftly to the reopening, the impact on growth should be small.”

--Maeva Cousin, senior euro-area economist. Read more analysis here.

On top of delaying the recovery, the shortages also have the potential to fuel inflation. With firms signaling in surveys that they’re passing on rising costs to customers, a spike in prices this year could fade less quickly than currently expected.

In July, Germany saw the biggest surge in imported goods inflation since the early 1980s, with merchandise arriving in the country 15% more expensive than a year ago.

The silver lining is that because supply shortages are a worldwide problem, business isn’t necessarily lost and the German recovery may turn out to be merely delayed.

“As soon as semiconductors are arriving in the car industry, there’ll be a forceful jump in production, and presumably surprisingly strong growth next year,” said Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg in London.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.