Macron’s Push for Affirmative Action Tests a Pillar of French Identity

Macron’s Push for Affirmative Action Tests a Pillar of French Identity

(Bloomberg) -- Said Argoug struggled for years to get a stable job, but doors kept closing. Not because he lacked skills, he says, but because he lived in a gritty urban area in northern France and had an Arab-sounding name.

“I remember when I first tried to get jobs with temping agencies,” Argoug, 26, said in the offices of his new employer, La Mobilery, a small web and app developer near Roubaix. “When they knew I came from Roubaix, I got no work.”

His job is part of a subsidized program that President Emmanuel Macron’s government is testing to combat employment discrimination. People from suburbs like Argoug’s are one-third as likely to find work as those from wealthier neighborhoods, the Labor Ministry says.

It’s France’s boldest attempt yet at affirmative action in a country that has struggled to integrate waves of immigration in the postwar era. Millions of people of North African background, many of them citizens, live in suburbs of hastily constructed tower blocks scattered around cities across the country. Known as banlieues, they are often isolated from transport connections. Their residents suffer from factory closures, poor educational achievement and decrepit public services.

While affirmative action is commonplace in the U.S., in France it’s known as “positive discrimination” and viewed with suspicion. Critics, especially from the far right, say perceived special treatment poses a threat to the central values of the country: liberty, equality and fraternity.

During his 2017 election campaign, Macron sparked an angry reaction when he espoused it as one solution for the high-unemployment banlieues. Marine Le Pen, his rival in the runoff vote, said at the time it was “contrary to the French Republic.”

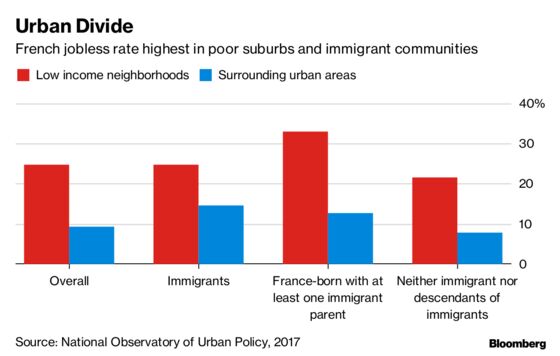

Yet it’s hard to climb the ladder in France. It would take six generations for those born in low-income families to approach the mean income, compared with an average of 4.5 years across the 34 OECD nations. And unemployment, especially among immigrants, is higher in France’s suburbs than in surrounding urban areas, according to the National Observatory of Urban Policy.

The program is part of Macron’s broader attempt to bring down unemployment by shaking up the labor market. The gap between the haves and have-nots and the perception that the president doesn’t care has cost him during the “Yellow Vests” protests roiling Paris and other cities.

Work contracts like Argoug’s qualify for subsidies, based simply on his home address. La Mobilery will receive 5,000 euros a year for the first three years he works there.

The government is testing the plan in the area around Lille, which encompasses Roubaix, and some suburbs of Marseille and Paris. If successful, it could be rolled out nationwide at the end of 2019.

In Lille, past employment policies were ineffective in aiding the underprivileged because they offered the same services and support irrespective of need, said Vincent Huet, director of home-help association AMFD, which is also hiring under the new program.

“Fair solutions are needed,” he said.

According to a 2016 study by labor statistics office Dares, employers are more likely to respond to job applications from candidates with French-sounding names, such as Aurelie or Julien, than those with North African name, such as Djamila and Faycal.

To escape those attitudes, Argoug used to cross the border to Belgium to work short-term jobs. “So long as you’re motivated, they don’t look at your name,” he said.

He grew up in Roubaix, where he went into vocational training to become an engineering assistant. But he didn’t find any work in that area and spent several years temping in factories, restaurants and elsewhere before the training program at La Mobilery, in nearby Tourcoing.

It’s early to say whether Macron’s trial will succeed on a larger scale. Bruno Ducoudre, an economist at French research center OFCE, warned that public money could be wasted: Businesses might have recruited people irrespective of the bonuses and France’s banlieues are in need of broader investment in transport and healthcare.

In Lille, authorities are already calling it a success after more than 1,000 contracts were signed in the first nine months. More people are moving in and out of the deprived areas for work, a trend that helps break down barriers and increase social mobility, said Nadine Crinier, regional director of the employment agency.

In September, Fatima Kethiri began working at the Pirates Paradise restaurant, on the outskirts of Tourcoing, on a long-term contract with good benefits.

“It was a permanent contract immediately,” said 50-year-old Kethiri, who spent years in part-time and temporary catering jobs. “That’s rare, really rare around here.”

The proximity of Pirates Paradise to the economically troubled area benefited owner Jerome Descamps when he needed to find 70 staff to set up the restaurant in September. Four of the new recruits, including Kethiri, will earn him cash bonuses, enabling him to take on extra workers, he said.

In addition to the subsidies, Descamps says those he’s hired and trained are better motivated and prepared to get involved. At the restaurant, replicas of pirate ships and rustic taverns surround a vast dining area where “waiter-actors” dash between tables, calling in orders on Bluetooth headsets.

“It’s not rocket science, we’re not doctors,” Descamps said. “Above all we are looking for people with personality.”

At La Mobilery, Argoug’s employers tell a similar story. To hire a developer usually requires 100 phone calls, and young skilled workers tend not to stay long, said customer relations director Fabrice Bellotti. Instead, La Mobilery asked the employment office to find job seekers who could be trained by the company. Bellotti says he didn’t realize a cash bonus was included, but the firm is eager to sign more people from the program.

“People who have a life story create a better link with the company, that lasts longer,” Bellotti said.

--With assistance from Samuel Dodge.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Anne Swardson at aswardson@bloomberg.net, Fergal O'Brien

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.