World’s Worst Economy Is a Threat to Mideast Rulers Rich or Poor

The region’s economies are running short of cash to placate struggling citizens.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Saudi ministers had just finished presenting an upbeat view of the kingdom’s economic prospects for 2019 at a December conference in Riyadh when a businessman sitting in the audience burst their bubble. After congratulating the officials on their growth predictions, Abdulaziz Al-Ajlan, a textile manufacturer, politely pointed out how little their outlook resembles reality. “Many small and medium-sized companies are shutting down,” he said. “We see companies firing Saudis.”

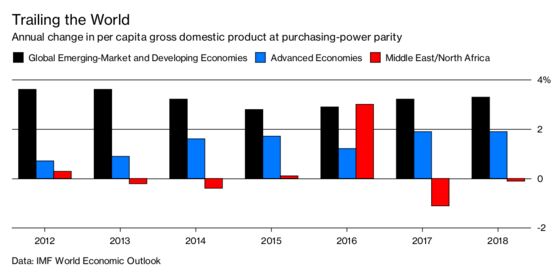

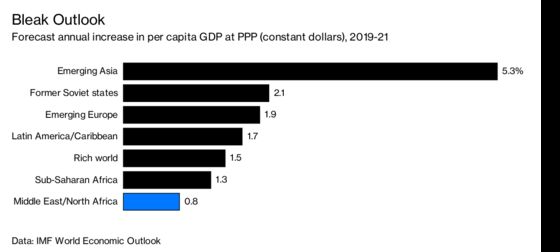

Four years of low crude oil prices have taken a toll on the Arab world’s biggest economy and other oil exporters, exacerbating a malaise that’s gripped the region since 2011. That year the Arab Spring protests swept across the Middle East, toppling regimes and wrecking economies. The oil-rich nations of the Persian Gulf mostly escaped the worst of it, but they weren’t going to take any chances and spent heavily to ward off unrest. Now, after four years of lower crude oil prices, they’re in financial trouble, too. The International Monetary Fund ranks the Middle East and North Africa as the worst-performing corner of the world economy since 2011, along with Latin America. Over the next few years, the IMF forecasts, the region will hold that title on its own.

Whether their countries are rich or poor, the area’s rulers face similar problems, from high youth unemployment to growing dependence on debt to bloated government wage bills. They’re finding long-term fixes hard to apply, as each painful step toward reform risks triggering discontent. Regional leaders can see the worst-case scenario unfolding in Syria, Libya, and Yemen, where instability eventually led to civil war. Tackling these economic challenges is “politically costly,” says Alia Moubayed, a managing director for Mideast investments at Jefferies International in London. Moreover, Arab governments, especially those in the Gulf, lack trained bureaucrats who can carry out technical reforms, she says.

To overcome that problem, many of them are seeking foreign help. In poorer countries, that often means the IMF, which has been busy in the region since the Arab Spring. It’s lent money to Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia—and gets blamed, unfairly according to its officials, for the austerity imposed under the credit programs.

Tens of thousands of Tunisian public servants went on strike in January to demand higher wages and protest spending cuts. Their powerful labor union accused the government of committing the ultimate sin: being even “more receptive” to the IMF agenda than Tunisia’s Zine El Abedine Ben Ali, the first dictator toppled by Arab Spring crowds. Prime Minister Youssef Chahed told protesters that raising their wages would simply require the country to borrow more.

Samir Radwan understands what it’s like to feel that kind of political heat. A labor economist, he was Egypt’s first finance minister after the uprising spread to his country in 2011. Because their populations are young and demand that change happen quickly, Arab rulers “don’t have the luxury of time,” he says. “I’d walk in the street, and people would tell me, ‘If we can’t get everything now, we’ll never get it later!’ There was no trust.”

Radwan held on to his job for less than a year. He reached a provisional $3.2 billion loan accord with the IMF, but the Egyptian army vetoed it, unwilling to add so much to the national debt. Five chaotic years later, with the presidency again in the hands of a military man, Egypt faced a crippling dollar shortage—and ended up borrowing $12 billion from the IMF. It had to stop propping up its currency as part of the agreement, triggering a slump in the Egyptian pound and a spike in inflation to higher than 30 percent.

In Saudi Arabia there’s enough oil money to make IMF loans unnecessary. Still, foreign consultants were brought in to draft blueprints for economic change, and they’ve faced the same kind of criticism for dashing off one-size-fits-all prescriptions. While demonstrations are banned, Saudi rulers remain alert to the threat of a public backlash, especially after the Jamal Khashoggi crisis. The Saudi columnist and critic was murdered by government agents, outraging the kingdom’s allies and spreading doubts about the job security of its de facto leader, Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman.

The crown prince, the architect of reform proposals intended to wean the economy off its dependence on oil revenue and state welfare, defended their ambitious scale in an interview with Bloomberg on Oct. 3. “If you aim low, that means it’s an easy target,” he said. “That means no one will try to work hard to achieve it.” And yet, after he enacted new taxes and subsidy cuts at the start of 2018, all it took was some grumbling on social media for his government to revert to its old ways, pledging billions of dollars in handouts to offset the belt-tightening.

Some economists say reforms such as the prince’s should’ve been made long ago. An IMF study found that countries do better at reducing oil dependence if they make the attempt while energy revenue is high, endorsing the maxim that it’s best to fix the roof when the sun is shining.

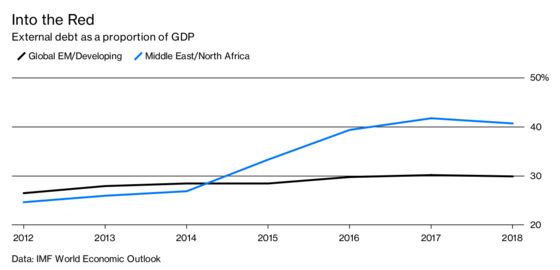

Since the oil crash, even rich Gulf Arab governments have been running large budget deficits. They may not be borrowing from the IMF, but they’re increasingly tapping global bond markets to plug the gap. Overall, countries in the Middle East and North Africa have accumulated foreign debt faster than their emerging-market peers since 2014, according to the IMF.

In the current stormy climate, countries with fragile public finances have looked especially exposed. Bahrain, the only Gulf country to see large-scale protests in 2011, came to the brink of a debt crisis last year and had to turn to the Saudis, who orchestrated a $10 billion bailout. The war in Syria has devastated the neighboring economies of Jordan and Lebanon, two of the most indebted Arab countries, which have taken in millions of refugees.

Except for war, many of these challenges are shared by Latin America, the only region doing as badly as the Middle East. But there’s one crucial difference. In most Latin countries, when the public isn’t happy with the economy, they can elect a new government to run it differently. That’s happened in the region’s three biggest economies in recent years, with sharp political shifts from the left to the right in Brazil and Argentina and in the opposite direction in Mexico.

Meaningful elections are rare in an Arab world largely ruled by absolute monarchs and military strongmen. Protests, sometimes violent, have been the main avenue for people to seek change. There are few signs so far that Middle Eastern leaders have managed to deliver it. “It’s not just about economics,” says Radwan, the former Egyptian minister. “It’s addressing expectations, addressing fears.” —With assistance from Jihen Laghmari

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Ben Holland

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.