Low Food Prices Are a Budget Problem for India’s Modi

A low inflation spell in an election year should be good news for any government, right? Wrong.

(Bloomberg) -- A low inflation spell in an election year should be good news for any government, right? Wrong.

For Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the subdued inflation numbers, due largely to low food prices, may present a budget problem. His government may have to shell out more to compensate farmers for low market prices of some crops under a plan announced this year with a view to double farm incomes by 2022.

“India’s falling food prices could become a bane for Modi,” said Soumya Kanti Ghosh, chief economic adviser at the nation’s largest lender State Bank of India. “A bumper harvest that’s led to crashing of food prices will increase the burden on the government to compensate farmers.”

In July, the government raised support prices of crops such as cotton, soybeans and paddy rice to ensure farmers get at least 50 percent more than the estimated production costs. That means in the event of a crash in market prices, the government would have to chip in and ensure sale of the produce by farmers at guaranteed prices.

The increase would cost the government an additional 150 billion rupees ($1.8 billion), Home Minister Rajnath Singh had said in July without elaborating. India aims to keep its budget gap at 3.3 percent of gross domestic product in the fiscal year to March 2019. But as the country gears up for a national election early next year, there are concerns that the government might not be able to stick to that target.

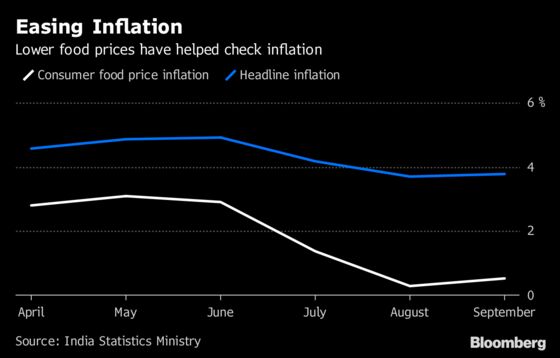

Consumer food price inflation eased to 0.5 percent in September from 2.8 percent at the beginning of this financial year in April. That’s helped bring headline inflation within the central bank’s medium target of 4 percent.

“Continued deceleration in food prices particularly in rural areas remains a serious cause for concern and could open up Pandora’s box in an election year,” Ghosh wrote in a note.

Three Plans

How much the government needs to spend also depends on the method used by states to support farmers. The government in September approved three plans that will ensure a 50 percent profit over the cost of production of crops including soybeans, mustard and pulses.

Under the price-support plan, government agencies will buy pulses, oilseeds and copra with the help of state governments, according to the farm ministry. The expenditure and losses due to procurement will be borne by the federal government as per norms.

Price-deficiency payment plan is proposed to cover all oilseeds. Farmers will be paid the difference between minimum prices and the rate at which they sell their produce in the market. Private companies will also be allowed to buy some crops. The existing plans of the government to buy crops including paddy rice, wheat and cotton will continue.

“Large scale procurement of commodities by the government would strain its finances and could lead to it missing its budget goals,” said Siraj Hussain, a senior visiting fellow with Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations and former farm secretary. “And it would also distort prices in open market. The government should investigate why prices are falling.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Vrishti Beniwal in New Delhi at vbeniwal1@bloomberg.net;Pratik Parija in New Delhi at pparija@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nasreen Seria at nseria@bloomberg.net, Karthikeyan Sundaram, Atul Prakash

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.