Job Losses Are Shifting to States, Cities After Business Rebound

Local Austerity Will Hold Back U.S. Rebound Like It Did in 2010

(Bloomberg) -- In Plymouth, Massachusetts, 2020 was supposed to be a big year. A summer-long series of events had been planned to mark the 400th anniversary of its settlement by English Puritans. The Mayflower II, a replica of the legendary ship that carried them to America, was ready for a relaunch after an extensive facelift.

That’s all off, thanks to Covid-19. Instead of splashing out on celebrations, the town of about 60,000 –- like communities of all sizes across the country -- is getting ready for some painful budget austerity instead.

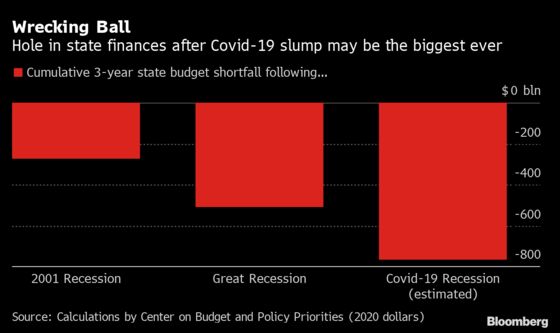

As the U.S. tries to lift its economy out of the worst slump in modern history, a looming round of spending and job cuts at state and local governments threatens to drag it back in. That happened after the last recession, too. Now the numbers look even worse.

Last week’s surprise jobs report showed American business back in hiring mode, but state and local governments were still laying off workers in May -- almost 600,000 of them, on top of the 1 million public employees who lost jobs in April. And with most localities starting a new fiscal year on July 1, the trend may persist into the second half of 2020.

Budget managers at every level can’t see much of an alternative. Commerce has screeched to a halt, opening big holes in their finances. Congress is deadlocked over sending more federal aid to the states, which in turn will have less cash to pass on to cities, counties and towns.

Plymouth has already begun laying off a handful of workers after cutting the budget for the coming fiscal year by $2.9 million. That’s likely to be just the start. The proposed saving matches the drop in state aid that the town suffered in 2009 during the last recession -- but it may take a bigger hit this time, and there’ll be lost revenue from other sources to make up too.

Municipal officials “are being asked to make a decision based on very few facts,” says Town Manager Melissa Arrighi. “What will state aid be? What will property tax revenue and excise taxes be, the hotel and meals taxes? We don’t know.”

‘Hollow Out’

Add a few zeroes and big jurisdictions like New York and New Jersey are in pretty much the same boat.

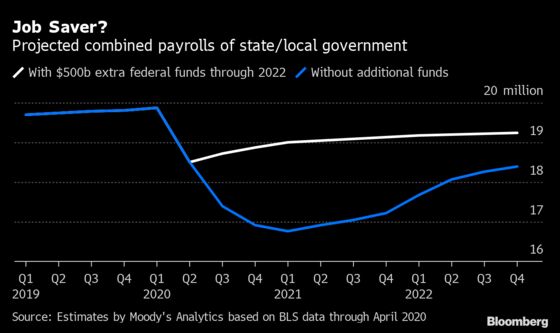

State-level shortfalls across the country in the coming fiscal year will add up to almost $300 billion, followed by another $200 billion in 2022, according to Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. If the federal government doesn’t plug the gap, another 1.5 million public-sector jobs are likely to disappear by next year, according to his calculations.

“These are teachers, fire, police, emergency responders, social workers -- the folks that we need in a crisis,” Zandi says. “If we lose these jobs, it’s just going to further hollow out middle-income America. And it’s every community across the country.”

Washington is split over how much of the tab it should pick up.

Congress appropriated $150 billion for state and local authorities, including funds to bolster health services, under earlier pandemic relief packages. House Democrats last month voted to send another $1 trillion -- but their bill was more gesture than policy. Republicans who control the Senate already said they would block it. The real bargaining remains to be done.

Spending and investment by state and local authorities accounts for about 11% of America’s economy –- a significantly larger direct share than the federal government’s. They manage school and health-care systems, and also spend large chunks of their budget on retirement care. They’re a key source of jobs for black Americans and women, who make up a bigger share of the public-sector workforce than the private one.

The Federal Reserve has stepped in with some temporary help by launching an emergency program that can purchase up to $500 billion in short-term municipal debt. Several weeks before Illinois became its first borrower, under a June 2 deal, the Fed backstop had calmed municipal debt markets -- reversing a spike in yields and capping borrowing costs for cities and states.

But in their current dilemma, that’s of limited use. Fed officials themselves have pointed out that Congress is better-placed to help.

“There has not been a significant enough transfer of funds from the federal government, which is able to borrow and doesn’t have to run a balanced budget, to states that do,” Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren said last month. “That will definitely be a significant headwind to the economy getting fully restored.”

Many local administrators are barred by law from running budget deficits by allowing their spending to outstrip revenue. And even where they aren’t, they can’t tap the currency-creating capacity of Congress –- known as the power of the purse -- like the federal government can.

Instead, when times are hard, these authorities are typically forced into the kinds of policies –- like raising taxes or cutting spending –- that make them even harder. In economics jargon, that’s known as pro-cyclical policy, and it’s generally been reckoned a bad idea for many decades now.

‘No Room for Error’

“They act as a multiplier,” is how Ernie Tedeschi puts it. “They exacerbate the downturn, because they have to make cuts at the same time the economy is bad.”

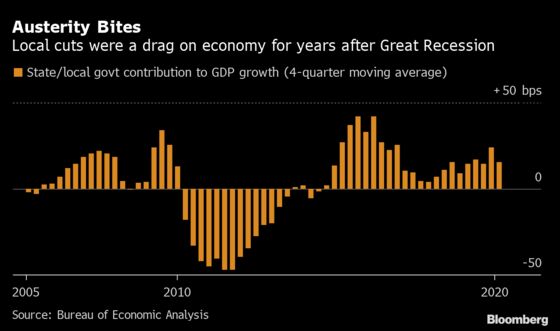

That’s what happened in 2010, when the national economy was starting to display some green shoots, according to Tedeschi, managing director of Evercore ISI and a former Treasury economist.

“State and local governments were essentially working against the recovery because they had to make those cuts,” he says. This year, too, they could deliver “the next big economic shock to hit the U.S.”

In Yonkers, a bedroom community outside New York City, the budget for 2021 foresees cutting as many as 168 jobs in the school system, because hoped-for state funding for education never arrived. And Mayor Mike Spano worries that the city is at risk of having to enact more layoffs if New York State cuts its budget again in a few months.

“Asking us to cut a police officer or a teacher is like asking us which limb to cut off,” says Spano. He’s hopeful that the economy’s gradual reopening will help the city, and that Congress will come through with more aid for states. “There’s no room for error here,” he says. “We’re teetering on the edge of a cliff.”

Back in Plymouth, a couple of hundred miles northeast, the Mayflower II is set to sail next summer instead. The 1620 anniversary celebrations haven’t been cancelled, says Arrighi -- just postponed. But it’s going to be a painful year getting there.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.