(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It may seem like a strange time for hedge fund manager Kyle Bass to exit his short bet against the offshore yuan – just as the trade looks to have a chance of becoming seriously profitable.

Almost four years after the long-time China bear made the wager, the currency is under increasing pressure amid a worsening trade conflict. If nothing else, fears of a global economic slowdown are giving traders a reason to flee to the haven of the dollar. That points to further weakness in emerging-market currencies, the yuan included.

It’s unclear when exactly Bass closed the position, which he held as recently as March. The Hayman Capital Manager founder no longer has a vested interest in China’s currency, he told Bloomberg Television in the U.S. in an interview Tuesday. Had Bass closed the trade in April, he wouldn’t have profited much. In July 2015, the offshore yuan was trading at around 6.2 per dollar; it was at 6.7 in April, a depreciation of about 7.5 percent.

So why now?

Put simply, it’s getting tougher to bet against the yuan offshore. Much has changed in the Hong Kong market since the People’s Bank of China’s surprise devaluation in August 2015.

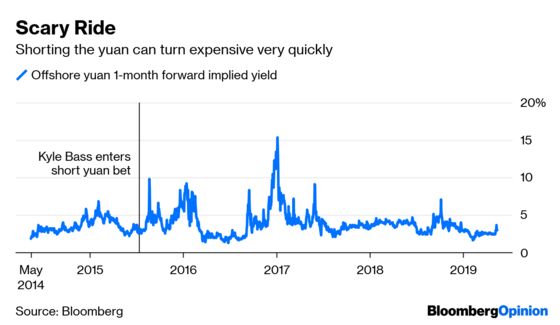

Shorting the yuan can get expensive quickly. In October, the last time the currency edged close to the psychologically important 7 level, the one-month implied yield for the offshore yuan shot above 7 percent, the highest level in more than a year. While the cost of borrowing remains contained so far this time around, taking on Beijing isn’t for the faint-hearted.

China’s central bank is becomingly increasingly assertive in the monetary sphere of the former British colony. Last September, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the city’s de facto central bank, agreed to let its Beijing counterpart issue yuan-denominated bills in the offshore market. This enables the PBOC to suck up liquidity and raise the cost of borrowing the currency, squeezing out shorts.

It hasn’t been shy with this new tool, issuing such bills at the end of October, right after the yuan hit 6.97; just before the Chinese New Year, when bears tend to wake from hibernation; and most recently, last week.

As I wrote in October, China has a strong incentive to devalue the currency, but only on its terms. Recent history is a guide. Since August 2015, the sharpest bouts of weakness have happened when China’s foreign-exchange reserves were largely stable. Beijing doesn’t want the yuan to depreciate when it’s in the headlines and the country may be accused of using its currency as a geopolitical tool. Stealth is the Chinese way.

There’s a lesson there for bears: If you want to short, do it quietly.

Make no mistake, though. Bass’s exit doesn’t necessarily mean he’s changed his view on the currency. There are other, subtler ways for yuan bears to act on their convictions. Shorting the South Korean won is one.

South Korea is almost as exposed to a trade war as China. A significant chunk of South Korean exports, equal to 3.2 percent of the country’s GDP, contributes to the Chinese supply chain that serves the U.S., Nomura Securities estimates. Korea’s current account surplus has already narrowed to 4.7% of GDP in the December quarter from close to 8% three years ago – and the trade conflict has yet to enter its nastiest phase. The won has been the worst performer in Asia since April.

The bears haven’t gone away. They may just have found another way to attack.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.