Japan’s Focus on Wealth Equality Rattles Financial Hub Dream

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s rhetoric of distributing wealth more equally appears to signal a change of priorities for Japan.

(Bloomberg) -- New Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s rhetoric of distributing wealth more equally appears to signal a change of priorities for post-pandemic Japan that may run counter to plans to improve the country’s presence as an international financial hub.

Just 12 months ago, leaders in Tokyo were hoping to capitalize on Hong Kong’s troubles to win back lucrative banking business. China’s crackdown on Hong Kong created an opening for Japan, according to then Finance Minister Taro Aso. His boss, former Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, pledged new tax breaks for financiers.

While Japan has some hope of using a green investment strategy to raise its profile among investors, the focus seems to have shifted toward what Kishida has billed as a new style of capitalism that reduces wealth inequality.

Kishida has promised boosting pay for nurses and caregivers, and spoken out against market short term-ism. Rather than cutting capital gains taxes, he floated the idea of raising them.

“Structurally, Japan is moving away from making Tokyo into an international financial hub,” said Shinichi Ichikawa, a senior fellow at Pictet Asset Management in Tokyo. “This new form of capitalism doesn’t really get people hoping that there’ll be growth and productivity, that Japan’s entering a new growth track.”

Plans to lure bankers back may have always been fanciful given the proximity of Singapore and Hong Kong to China’s booming market and Japan’s higher taxes. But some analysts worry that a golden opportunity may still be lost amid flip-flopping policy objectives.

The problem is that investors don’t want to put money into markets that don’t grow, said Ichikawa. Even during the years of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, when Japan’s stock market came back to life, the government didn’t really tackle structural reforms that might have led to longer-term growth.

“That trend is even stronger now,” Ichikawa said.

Kishida’s moves have already spooked markets with talk of higher capital gains taxes and new regulations surrounding share buybacks.

While Kishida hasn’t made it completely clear what his new form of capitalism means, Nobuo Sato at Harvard Business School Japan Research Center says so far it sounds like there may be a retreat from Abenomics’ focus on improving Japan’s productivity and profitability.

“I think foreign investors will be sensitive to the implications of this change,” said Sato, who’s executive director at Harvard’s center in Tokyo. “If foreign investors feel Japan is going back to the pre-Abenomics time, they’ll be disappointed unless companies really improve their profitability.”

Shinichi Tagawa, deputy director of Marubeni Research Institute, adds that Japan has been at a disadvantage for decades due to the language barrier and higher tax rates.

“There are also high hurdles for those who are fund managers who are trying to set up a new business,” said Tagawa, who says he struggled to set up funds in Japan in the past. “Japan still has a stronger tilt toward protecting domestic banks and institutions.”

Still, despite the changes in messaging from the top, Japan’s central government has done some things in the past 12 months to attract more banking business.

It exempted foreign residents from inheritance taxes in some cases and effectively cut taxes on income from fund performance. The government also opened a one-stop center for foreign financial firms this year, so they can start filing paperwork in English.

At the same time, the cities of Tokyo, Osaka and Fukuoka are pushing ahead with their own plans to become international financial hubs.

The roadmap issued by Tokyo last month, the first overhaul in four years, shifts gears to try to take advantage of the boom in green and digital growth markets. The plan calls for almost tripling the number of asset management companies in the city to 900 by 2030, while more than quadrupling the number of fintech firms.

Green Finance

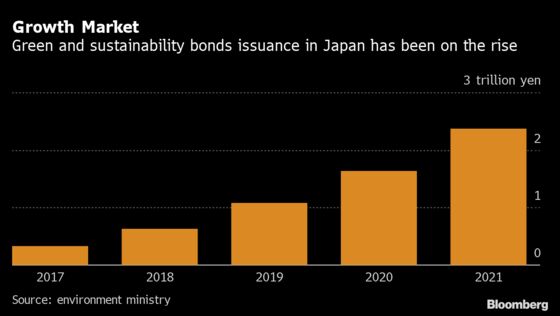

Tokyo’s plan also calls for raising the amount of green bond issuance in Japan from 800 billion yen ($7 billion) in 2020 to 3 trillion yen by the end of the decade.

“When the accepted order is shifting, that’s a time of great opportunity,” said Yasushi Takagi, an official at the Tokyo metropolitan government tasked with making the capital into a global financial city. “Ultimately our goal is economic growth. Creating an international hub is a major way of making the financial industry more active, which in turn should also lead to economic growth.”

Masayori Shoji, head of fintech promotion at KPMG Consulting Co. argues that Japan also has an edge because their manufacturers are more stringent in supply chain transparency, a key factor for green financing.

While Hong Kong and Singapore are already ahead of Tokyo in building information platforms for green financing, for example, there’s still hope Japan can catch up in this new field, says Takuya Nomura, a senior economist at Japan Research Institute.

“In the world of green finance, Hong Kong and Singapore are running ahead, but Japan is still close enough to be able to catch up,” said Nomura. “This may be Japan’s last chance.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.