Is the U.S. Recession Over? Official Panel Isn’t Ready to Say So

The panel of economists who judge the dates of U.S. recession is finding that declaring an end to this year’s downturn is tougher

(Bloomberg) -- The panel of elite economists who judge the dates of U.S. recessions is finding that declaring an end to this year’s downturn is tougher than calling its start.

The National Bureau of Economic Research’s business cycle dating committee announced in June that the Covid-19 recession began just four months earlier in February -- the shortest time yet for a decision that can take a year or more.

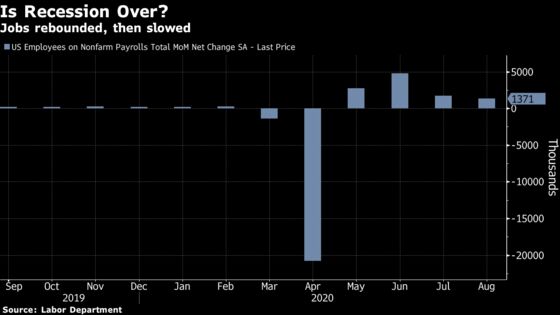

Most broad indicators including jobs, consumer spending and manufacturing have turned positive since May, suggesting that the slump could already be over; third-quarter figures are projected to show a record increase in gross domestic product, following the prior period’s record contraction.

But the NBER panel has held off from an official call on the recession’s end. While committee deliberations are secret, some individual members indicated they’re waiting for more evidence of a sustained recovery amid concerns about a slowdown in employment gains and risks of a renewed downturn.

If that happens, it would spur debate on whether it’s part of the same recession or constitutes a second recession.

Figures in recent weeks show a gradual rebound is ongoing, but it could be undermined by the expiration of some federal aid programs and the fact that the coronavirus continues to restrain business and schooling around the country. The U.S. surpassed 200,000 recorded Covid-19 deaths this week, prospective vaccines are still in testing and the cooling weather threatens a fresh wave of infections, which could bring a leg down in activity.

“Here is the worst-case scenario: No new stimulus, continued chaotic management of the virus, a real second wave as some epidemiologists predict,” said James Stock, a Harvard University economist on the committee. That could lead to “a second round of lockdowns leading to a decline in GDP,” he said.

Committee members would then be faced with the question of whether that decline would be a new recession or part of the one that was dated to February.

Stock said it’s correct to consider this “good question,” and it’s “too early to assess” the answer. A U.S. recession lasting just two or three months would be the shortest on record, following a 10-year expansion that was the longest, according to NBER data on business cycles back to the 1850s.

Read More: U.S. strimulus gridlock seen knocking fourth quarter growth

While the NBER’s judgment may not have practical implications for Americans, the debate among its members illustrates the complexity of the economy’s current state.

In addition, a call on the recession’s end ahead of the Nov. 3 election would come in the final weeks of a bitterly contested presidential race, potentially supporting President Donald Trump’s view that the economy has moved past the downturn. The nonpartisan NBER says politics doesn’t affect the timing of its declarations.

Northwestern University professor Robert Gordon, another committee member, said he believes the recession ended in April. “Any new downturn -- if satisfying the criteria of depth and diffusion -- would be classified as a new recession,” in his view.

It’s far from certain the committee is ready to agree. The fear of a second leg down suggests a declaration will be delayed, said Harvard professor Jeffrey Frankel, who served on the committee for more than a decade through 2019.

“The risk of a renewed downturn is a reason for the committee to wait as usual -- often a year -- before declaring the trough,” he said, adding that’s true “even if one doesn’t buy my judgment that the probability of a renewed negative quarter is especially high.”

This year’s recession call was unusually fast. Typically, the committee has taken six to 21 months to make such declarations of peaks or troughs in activity -- otherwise known as the beginning and end of recessions.

While many economists use the shorthand for a recession as two consecutive quarterly declines in GDP, the NBER defines one as “a significant decline in economic activity” and looks at a variety of indicators.

“The committee takes whatever time is needed to identify a trough reliably,” said Stanford University professor Robert Hall, chairman of the committee.

The committee members who agreed to be interviewed are united in seeing the jobs data as slowing in recent months. While there was a surge in activity in May and June, that mainly represented workers being recalled to jobs after temporary layoffs, while permanent job losses have continued to increase, Hall said.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, who’s repeatedly warned that the outlook looks more difficult now, “is almost certainly right that the next points of unemployment decline will be harder,” Hall said.

The U.S. unemployment rate has fallen to 8.4% in August from a peak of 14.7% in April. About half the 22 million jobs lost in March and April have been regained.

“Personally I don’t think we will have another recession but rather a long, slow, and painful recovery from where we are now,” Northwestern’s Gordon said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.