Indonesia Walks a Fine Line Between Bailouts, Downgrades

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Since surviving an IMF bailout and violent change of government during the Asian financial crisis, Indonesia has shown an uncanny resilience in bouncing back from global selloffs. As soon as the dust settles, investors are lured by higher yields and the promise of a young and vibrant population. Foreigners now own more than 30% of the country’s sovereign debt.

This time, they may not return. The key reason is the pile of debt at state-owned enterprises that President Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, has built up since taking office in 2014. As the coronavirus outbreak forces SOE defaults and restructuring to play out on the international stage, investors are now wondering whether Jakarta — which still enjoys an investment-grade rating — can keep its distance and avoid being dragged into one bailout after another.

The virus claimed its first corporate victim from the public sector in April, when Perum Perumnas, a real estate developer, defaulted on a 200 billion rupiah ($13.4 million) note. But PT Garuda Indonesia, the national airline 60% owned by the government, makes a better example of the debt labyrinth that Jakarta can’t easily escape.

The flagship carrier is in trouble. Garuda has a $500 million dollar sukuk due June 3, but sat on only $299 million cash at the end of 2019. The government plans to restructure the financing and arrange another $500 million for working capital. But it’s ruling out a direct cash injection, Bloomberg News reported Monday.

If Garuda was left to fend for itself, other SOEs would follow it into distress. The airline buys fuel from PT Pertamina and airport services from PT Angkasa Pura, and is a large client of state-owned mega banks. Debt to other SOEs accounts for more than 30% of its total liabilities, or almost $1.2 billion, data compiled from the company’s 2019 filings show. State-owned insurer Asuransi Indonesia Kredit PT guarantees the class A tranche, or 90%, of 2 trillion rupiah in asset-backed securities issued in July 2018, which are backed by ticket sales to Jeddah and Medina. There’s a problem: Saudi Arabia has suspended Muslim pilgrimages due to the pandemic.

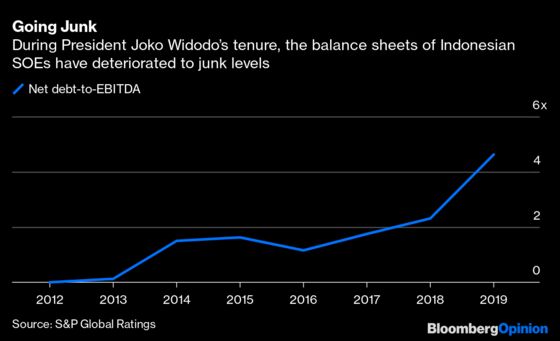

During Widodo’s first five-year term, the balance sheet of Indonesia’s state companies went from squeaky clean to junk grade. An infrastructure enthusiast but pinched by the Southeast Asian nation’s twin trade and fiscal deficits, Widodo found his model in China, where state-owned entities shoulder much of the financing burden of national development. The most visible success of his strategy was a building boom that culminated with the opening of the capital’s first subway line last year.

Now, the president has to face an ugly reality. We can expect the ratio of net debt at Indonesian SOEs to range from 4.5 times to 5.5 times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization this year, compared to 1.6 times from his first year in office, S&P Global Ratings estimates.

The government needs to resist outright capital injection into Garuda for a good reason — its own coffers are empty. To blunt damage from the pandemic, Indonesia removed its long-time 3% fiscal deficit cap and raised it to a new target of 5.1%, translating to additional financing needs of $27 billion.

This highlights the challenge that Widodo took on when he launched his infrastructure drive almost six years ago. Under his presidency, SOEs have become more pervasive than in any country except China, according to a recent survey by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Can he walk a fine line between placating their interests and keeping the government’s own balance sheet clean?

China has already paid a heavy price. Its sovereign bond market remains underdeveloped. This is due in part to foreign buyers being wary of SOE debt, even though Beijing repeatedly says it doesn’t guarantee obligations issued by such enterprises — they’ve been allowed to default since early 2015 — or by local government financing vehicles.

Indonesia will need to establish this kind of separation, at a minimum. Last month, S&P revised Indonesia’s credit outlook to negative while keeping the BBB rating. If Jakarta starts to bail out its state enterprises, its investment-grade rating may vanish.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.