(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Indonesia was never keen to be part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. That hasn’t stopped it from embracing the Chinese way when it comes to financing roads and railways.

The government of President Joko Widodo plans to spend more than $400 billion building airports, power plants and other infrastructure in the next five years, Planning Minister Bambang Brodjonegoro told Harry Suhartono and Karlis Salna of Bloomberg News in an interview last week. That’s even more than the Indonesian record of $350 billion that Jokowi, as he’s known, targeted in his first term.

The question is how to finance such ambitious plans. Indonesia has twin trade and budget deficits, and the government has been careful to keep the latter within 3% of GDP, an international standard for fiscal prudence.

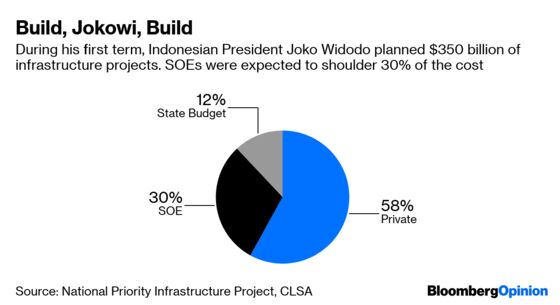

The country has found its model in China, where state-owned enterprises shoulder much of the burden. Indonesia’s 2016 plan to accelerate 245 national strategic projects assumed that 30% would be financed by SOEs, more than twice as much as the state contributed. SOEs have become more pervasive in Indonesia than in any country except for China, according to a recent survey by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In less than a decade, the balance sheets of Indonesia’s state companies went from squeaky clean to junk-grade. In 2011, a typical SOE could pay off all of its debt with just one year of pretax profit; as of 2017, that had ballooned to 4.5 years, S&P Global Ratings estimates.

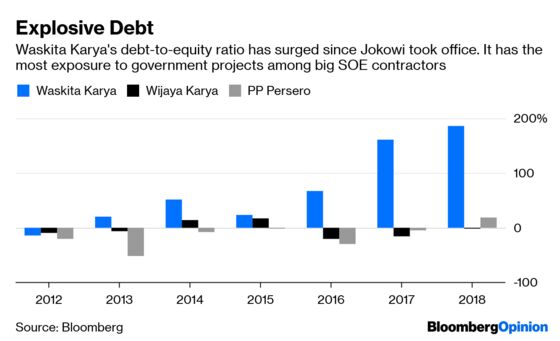

Take PT Waskita Karya, one of the three largest listed SOE contractors. The company has the most exposure to government contracts, and its debt burden has exploded since Jokowi took office.

This reflects the upfront cost of taking on government contracts, which requires SOE buildings to tie up billions of dollars in working capital. Often, contractors don’t get paid until projects are 100% completed. Assets don’t see good cash flows until they’ve been operating for years. Sometimes, construction get pushed back. The controversial Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway, for instance, was delayed by more than two years because of land acquisition issues.

PT Jasa Marga, Indonesia’s largest tollway operator, is a good example. The company needs an additional 35.1 trillion rupiah ($2.4 billion) of capital to double its road network in two years, Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Charles Shum estimates. That’s equivalent to 5.5 years of operating profit, putting Jasa Marga at risk of breaching debt covenants.

To finance these projects, SOE builders have been selling debt to foreign investors and getting loans from China. For example, PT Wijaya Karya raised about $400 million in January 2018 selling Komodo bonds – rupiah-denominated securities sold in the offshore market – and obtained 80 trillion rupiah in loans from China Development Bank, a state-owned policy lender.

However, both channels are fraught with potential dangers. Because of their junk ratings, SOE builders can issue only short-term notes, exposing them to refinancing risk when undertaking long-term projects. Meanwhile, cheap loans from Beijing became politically sensitive as anti-China sentiment rose during Jokowi’s bid for a second term.

As a result, most financing has come from Indonesia’s government-controlled banks – just like in China. Bank loans to non-financial SOEs ballooned to 8% of the system’s total, from only 3% a decade ago, data provided by Bank Indonesia show.

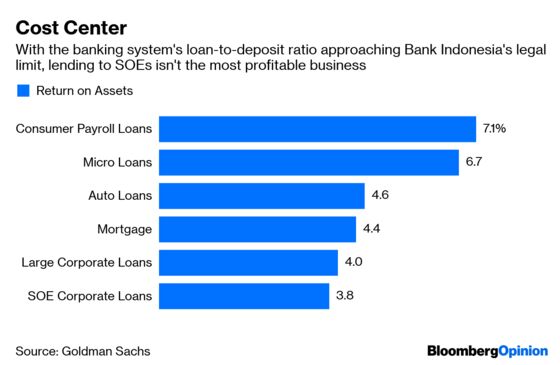

No doubt, these have been made on favorable terms. The 6.7% return on a micro loan to the private sector is much higher than for an SOE advance. And banks are quick to forgive. In March, Jasa Marga breached the covenants on a loan facility arranged by PT Bank Mandiri. It was spared repercussions, though, having obtained a waiver statement from creditors in December.

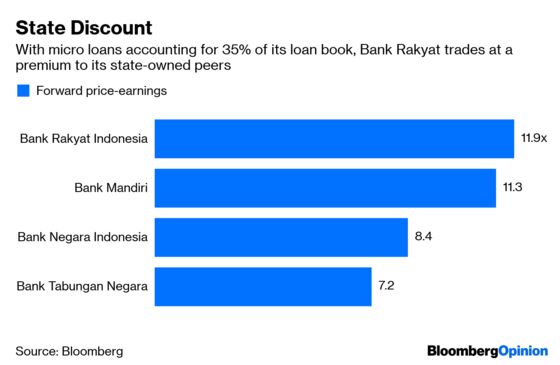

SOE banks know that Indonesia’s vibrant private sector provides more profitable lending opportunities. PT Bank Rakyat Indonesia, the country’s largest state-owned lender, aims to raise its micro-loan ratio to 40% by 2022, from 35% now. But it’s unclear how the bank can make that happen. At 91%, its loan-to-deposit ratio is edging closer to the legal limit. The lender either has to scale back SOE lending or abandon its expansion plan.

Jokowi is right to lean on infrastructure to reach the 7% GDP growth target he set when taking office in 2014: The country needs better transport links and energy supplies, and such projects promise long-term economic benefits. At the same time, he should be wary of how Indonesia will pay for it. China may not be the only country in Asia that needs to worry about a possible Minsky moment.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.