Thinking Big About Covid-19 and Monetizing Public Debt

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A Holy Grail of policymaking since the end of the 1970s high-inflation era has been to stop turning public debt into interest-free money. In emerging economies like India, where the idea made a late entry, this dogma is threatening to get in the way of mounting a robust response to the coronavirus.

The reluctance to surrender hard-won victories is understandable. Swapping the debt associated with grand anti-poverty programs with cheap-to-print currency used to have an irresistible sway. The belief that only an Odysseus-like central banker can avoid being seduced by the politicians’ siren song and steer the nation to price stability wasn’t an easy sell.

But as overseas capital and international trade became more important than foreign aid, the yearning for permanent low inflation won out. In 1997, the Indian government gave up its power to get any number of its treasury bills bought by the central bank, restricting itself to a temporary overdraft. For financing, it had to go to the bond market.

In 2015, the bank moved to inflation targeting, raising hopes that the rupee would one day be used and held internationally, giving India a durably lower cost of capital. That was then. Now, workers are stranded without jobs or pay. Firms are failing, lenders are piling up bad credit, and state governments are running out of funds. It’s crucial to secure financing for at least 13% of gross domestic product in federal and state deficits. That’s a $342 billion shortfall.

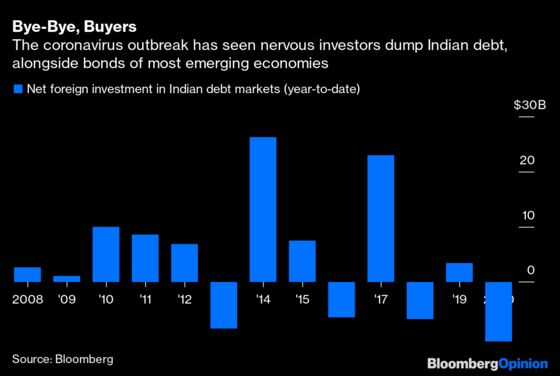

The government is unlikely to lean on the Reserve Bank of India for funding until at least September, the Business Standard reported Tuesday. Yet with foreign investors fleeing emerging markets, pretending that funds could materialize in the bond market is delusional. C. Rangarajan, the RBI governor who signed the 1997 agreement to end back-door monetization of public debt, believes its return may be inevitable.

The right way to bring it back is by the front entrance. Stealth operations, like the RBI propping up a sovereign bond auction by asking dealers to buy on its behalf, according to a news report by Cogencis, are pointless subterfuge. It’s time the authority openly bought notes from the government by printing new money.

More than a grand vision, the bold approach needs details, which the middle managers in the Finance Ministry and the RBI need to fill in. For a start, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government should sell stakes in every company that’s on the block for privatization — as well as some that aren’t — to a special purpose vehicle run by, say, the National Investment and Infrastructure Fund Ltd., which has demonstrated fund-raising clout with global investors. The SPV will finance the purchase by issuing sovereign-backed debt. When market conditions improve, it will sell its stakes and redeem the bonds.

Whatever is raised should be deployed in an infrastructure plan that has health at its centerpiece. This will boost construction and create jobs. Subsidized loans should be made available, but only to businesses that keep at least as many people on their payrolls as they had in February and make suppliers’ invoices available on a bill-discounting platform so vendors can get paid. It’s the workers and small and mid-size enterprises that are getting hammered by large companies passing on the pain of dislocation. In some private firms, such as airlines, the government will have to infuse equity.

It’s time to establish credibility with action, and not by observing institutional niceties. Excessive virtue-signaling by Japan serves as a cautionary tale. After its 1980s asset bubble burst, the monetary authority got tangled up in unconventional policies. Yet, the Bank of Japan bound itself to a “bank note rule,” vowing not to own more government bonds than could be repurchased by the private sector with the currency in circulation. It took Governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s April 2013 bazooka to demolish the illusion that the BOJ was providing a temporary shelter for public debt — not swapping it with money forever.

India’s central bank also needs to think beyond cutting interest rates and flooding banks with liquidity. In McKinsey & Co.’s estimates, gross domestic product this year is on track to shrink by 2% to 3%. Deeper declines aren’t ruled out. The jobless rate is estimated to be near 23%. With no risk of inflation except perhaps in some food items, there’s no need to be coy about monetizing deficits. Being smart will do.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies and financial services. He previously was a columnist for Reuters Breakingviews. He has also worked for the Straits Times, ET NOW and Bloomberg News.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.