In a Forever Trade War, U.S. Companies Take Cover as Best They Can

In a Forever Trade War, U.S. Companies Take Cover as Best They Can

(Bloomberg) --

Happy Gorilla Game Studio was staring at ruin this summer even before its first board game was unloaded off the boat from China.

Chip Boyd and Neil Gilstrap, co-founders of the crowd-funded startup in the niche world of Dungeons and Dragons-style pastimes, had promised backers early copies of War for Indagar, a demon-laden fantasy.

They hadn’t anticipated tariffs on Chinese imports. As they waited for their boards, special dice and figurines of the Bright Lord and Grinning Tyrant to arrive, they feared they would have to ask backers for more money, eat the $4,300 in tariffs themselves or roll the costs into their next project and potentially doom it.

“There was very little chance of digging out of that hole,” said Boyd, who is based in Virginia.

Businesses across America are straining to cope with import taxes and protectionism under the Trump administration, which next week hosts senior Chinese officials for the highest level talks since July — and just days before another threatened tariff increase.

For Happy Gorilla, a company built on fun, the levies meant a joyless summer. Elsewhere, an Italian manufacturer of factory machinery bought a Colorado subsidiary to ensure a toehold in the market. A crib manufacturer dumped parts of its product line that no longer made financial sense. And a decor-maker in California hunted for elusive upside.

Some U.S. businesses are warning they may close if they don’t get a yearlong reprieve, or “exclusion,” from tariffs that by year-end may touch some $500 billion in Chinese imports, said Paula Connelly, a Boston trade lawyer.

“It’s going to be hard to say no to someone who says, ‘Unless I get this exclusion, I’m gong to have to shut down,’” Connelly said.

Bloomberg spoke with companies across the country to see how they’re coping with uncertainty.

Geekdom Constrained

Colossal video games like Fortnite grab attention, but lower-tech gamers are up all night playing things like War for Indagar. Hobbyists have backed them to the tune of $700 million since 2009, Kickstarter reports, and games are the crowdfunding platform’s biggest category by dollars pledged.

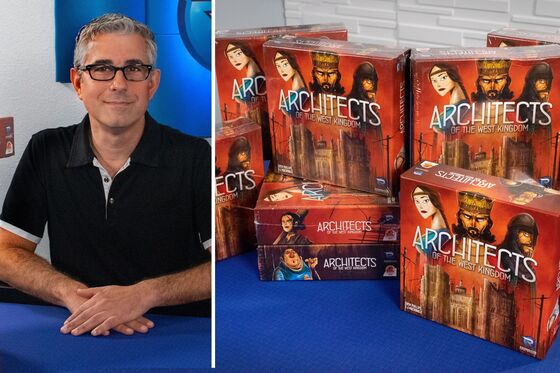

Ultimately, Happy Gorilla escaped its fate when President Donald Trump delayed tariffs on some consumer products until Dec. 15, and the company has been sending copies to supporters at the promised price. Still, the industry fears that a 15% tariff set to hit toys and other consumer goods in December, may later rise to 30%. “It changes week to week, kind of on a whim,” said Scott Gaeta of San Diego, California-based Renegade Game Studios.

A 30% tariff could cripple games, which typically sell for $40 or $50, Gaeta said. Renegade is ordering extra copies of its best-selling titles for storage ahead of the December tariffs, such as the medieval village-building game Architects of the West Kingdom. Others are considering delaying or nixing new games with lots of miniature plastic pieces, which carry higher price points and thus more risk.

Renegade is a midsize studio and will ride out the tariffs, but smaller shops “might not be working on the best margins to begin with. Tack on these tariffs, and you’ll have a lot of them underwater,” Gaeta said.

Buying American

Last year, executives at SCM Group S.p.A., an Italian manufacturer of furniture-making machines, heard the tough talk with alarm: Trump was threatening retaliation against the European Union over what he saw as unfair trade. Meanwhile, domestic cabinet makers were pressing the International Trade Commission to punish Chinese cabinet makers for what they said was dumping in the U.S.

SCM makes many of its computerized cutting devices in Rimini, a picturesque town on the Adriatic Sea. Spooked, SCM last October purchased a Colorado company that also makes routers, Diversified Machine Systems, for an undisclosed sum. The move lets the Italian firm target new industries, offer cheaper machines — SCM’s average order price is around $150,000 — and reduce foreign-exchange risks. But it also gave it a hedge against the unknown.

Its new American unit can be a base for future expansion, “and it makes us more independent from the risk of an increase in export duties,” Chief Executive Officer Andrea Aureli said by email.

Other foreign companies are considering similar moves, said John Ling, a consultant from Greenville, South Carolina, who helps Chinese companies invest in U.S. factories. Ling is fielding many more calls lately from companies considering a presence. Holding them back: worry over the Trump administration’s moves to curb immigration and foreign visas.

Baby Beds Bounced

Some 90% of safety-related baby gear comes from Asia, mostly from China, according to the Juvenile Products Manufacturers Association. The U.S. Trade Representative left car seats off the tariff list after makers argued parents would use outdated models. But companies like Vancouver-based Storkcraft Manufacturing Inc. are stumped by the decision to keep cribs — a key safety concern among parents.

“It doesn’t make sense to me,” said Adam Segal, the chief executive officer.

With sales north of $100 million, Storkcraft sells furniture and cribs under its own brand online and in big-box retailers, and produces Graco-branded products. It has tried to find suppliers outside China, “but it is difficult, if not impossible, to replicate the infrastructure, safety and capacity,” Segal said.

For now, it has bumped up the price of a popular $199 crib by $40 apiece and seen sales of some models decline. It has discontinued products that weren’t selling at the new, higher price points, he said. Some manufacturers are petitioning for a one-year reprieve, said Lisa Trofe, managing director of the Juvenile Products Manufacturers Association.

Leveling the Field

Jonathan Bass got an eight-year head start on shifting production out of China, but while everyone else races to Vietnam and Malaysia, he moved closer to home. His company, PTM Images, designs mirrors, frames and wall art for retailers such as TJ Maxx and Bloomingdale’s from its studio in West Hollywood, California. Bass had sourced goods from China until 2011, when he grew dismayed at his supplier’s willingness to skirt California’s environmental regulations. That year, he opened his own factory in a Mexican border town south of Arizona.

The move yielded shorter shipping times, but his worker costs have been higher than they would’ve been in China, even with the latter country’s run-up in wages. Bass pays his workers around $4.50 an hour, where comparable workers in China might expect $3.60, according to market researcher Euromonitor. Bass also wasn’t expecting energy costs in Mexico to be as high as they are, and so he schedules shifts during off-peak power usage times.

“You can’t play low-cost in Mexico in comparison to low-cost in China or low-cost in Vietnam,” Bass said.

Bass has tried to improve his margins by adding production of high-end furniture, under the Badgley Mischka brand, at his Mexican wall decor factory. Meantime, he sees the 25% duties on Chinese furniture and wall decor as putting his factory on a even footing, even if China’s moves to devalue its currency offset some tariffs.

“It makes everyone more competitive, but the issue is, are they staying?” Bass said. “Will there be a flip-flop? No one is secure in the direction of where we’re going.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stephen Merelman at smerelman@bloomberg.net, Anita SharpeSarah McGregor

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.