Immigration Quotas of 1920s Failed to Aid U.S.-Born Workers’ Pay

Immigration Quotas of 1920s Failed to Aid U.S.-Born Workers’ Pay

(Bloomberg) --

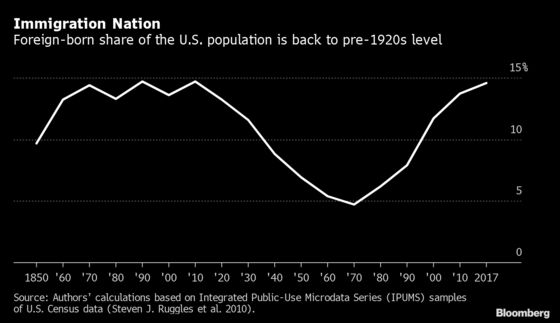

The closing of American borders to mass migration from Europe in the 1920s, one of the biggest immigration policy changes in the country’s history, didn’t raise wages for U.S.-born workers in the areas most affected by the shift, according to a transatlantic team of researchers who say the history offers important lessons for today.

Quotas effectively limiting annual immigration by more than 75% targeted Europe yet exempted Mexico and Canada, encouraging labor flows from those countries to American cities and new capital investment in rural areas, the researchers said in a working paper distributed by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

“Substantially walling off the U.S. economy to new immigration did open up some employment opportunities for U.S.-born workers who moved to urban areas to take jobs previously held by immigrant workers,” the economists wrote. “However, using immigration restriction to raise the earnings of U.S.-born workers more broadly is unlikely to be effective given the many factors that can substitute for immigrant workers.”

Despite the loss of immigrant labor supply, earnings of U.S.-born workers actually declined as more-skilled American-born workers, plus the unrestricted immigrants from Mexico and Canada, moved into cities affected by the country-specific quotas, completely replacing European immigrants, they said.

The analysis offers a lesson about the potential for substitution and other unintended consequences: Losing immigrant workers encouraged farmers to invest more in equipment, which discouraged some workers from entering the agricultural labor force. That suggests that outsourcing or automation could replace lost immigrants -- and, in turn, American-born workers.

The conclusions come from a team of five economists: Ran Abramitzky of Stanford, Philipp Ager of the University of Southern Denmark, Leah Boustan of Princeton, Elior Cohen at the University of California at Los Angeles and Casper Hansen of the University of Copenhagen. The research follows an October working paper by authors including Abramitzky and Boustan showing children of U.S. immigrants out-earn their parents and have more upward mobility than their American-born peers.

“Today, these sources of substitutability may be automation in the manufacturing sector or the off-shoring of high-skilled tasks like computer programming or legal services,” the researchers wrote in the new paper.

Thinking about immigration barriers in isolation without also considering other strategies that can be used to adjust will probably lead to incorrect assumptions, Boustan said in an interview. If an immigrant labor supply is turned off, it doesn’t necessarily mean that employers will turn to a high school graduate in the U.S. or someone with an associate’s degree, she said.

U.S. workers are one alternative, but there are also robots, and workers employed abroad whose offshore work is imported, “so it’s not obvious that the substitution is going to go from immigrants to U.S. workers,” she said, citing the increasing amount of professional work that can be separated out and moved abroad, from legal and medical to finance and programming.

“Immigration is one source of labor supply on a whole menu, so if we take that item off the menu there will be an alternative,” she said. “I’d urge caution with a very simplistic idea that one immigrant worker deterred from entry necessarily means one new job for a worker in the U.S.”

Elsewhere in the paper released Monday, the economists conclude there’s no evidence U.S.-born workers and other unrestricted groups are attracted to rural areas after the border closure. “This finding is consistent with concerns of contemporary farmers who worried that U.S.-born workers would not replace their farm labor force primarily composed of the foreign-born,” they said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeff Kearns in Washington at jkearns3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Scott Lanman at slanman@bloomberg.net, Jeffrey Black

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.